In April 1952, a 26-year old man stood before the Northern Rhodesia Chief Justice, who had been asked by the Attorney General to consider whether this young man was ‘a danger to peace and good order’ and whether he had been ‘inciting Africans against Europeans’. The judge was further asked to consider whether he found grounds to recommend to the Governor that the man should be deported. Following two days of court hearings, the young man was solemnly declared to be ‘a danger to peace and good order’, and, after a fruitless appeal to the High Court and eight months in jail in Livingstone, he was deported to England, a country he had previously neither visited nor lived in. That young man was one of the few white men to stand up against white supremacy in Northern Rhodesia. He was a member of Harry Mwaanga Nkumbula’s African National Congress (ANC), and is one of the heroes of Zambia’s struggle for independence. His name is Simon Ber Zukas. On 27 September 2021, Zukas died peacefully in his sleep at home in Lusaka. He was aged 96. Who is Zukas and how did he end up in prison?

Born 31 July 1925 in Ukmerge, Lithuania, Zukas came to Zambia on 26 July 1938 to join his father, a Jewish settler who had earlier migrated to the industrial Copperbelt and established himself as a successful trader. After completing his secondary education in Luanshya and colonial Zimbabwe and serving briefly in the armed forces during the Second World War, Zukas went to South Africa to read for a degree in Civil Engineering at the University of Cape Town in 1947. His time in South Africa, coinciding with the inauguration of apartheid, thrust him into radical student politics where he distinguished himself as a shrewd operator and rehearsed his later confrontations with the African colonial apparatus.

Upon graduation in December 1950, the young engineer returned to Zambia where he learnt of the colonial government’s plans to federate the country with Zimbabwe (then Southern Rhodesia) and Malawi (Nyasaland). Arguing that this would serve the interests of the white settler minority, further disadvantaging the black majority and delaying the attainment of independence, Zukas put aside his professional and personal considerations to join the ANC, the main nationalist movement at the time. Though constituting a risk to his own life, his decision to confront those who perpetuated injustice and become an active participant in the struggle for independence was a statement of his commitment to equality and was in sharp contrast to most whites at the time, whose support for African causes was limited to hushed statements from the safety and comfort of home.

When white settlers and the colonial regime intensified their campaign for the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, Zukas – alongside other young, militant nationalists like Justin Chimba, Reuben Kamanga, Jonathan Chivunga, Nephas Tembo and Abner Kazunga – formed, in April 1951, the Anti-Federation Action Committee, of which he became secretary, and began rallying thousands of Zambians, especially those on the influential Copperbelt, to resist the proposed plans. Noting his growing influence in the nationalist movement, the colonial authorities ordered him to abandon his opposition to the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland and, when he defied the directive, sent him to prison in April 1952. He remained in detention until December that year, when he was deported. But Zukas never turned his back on Zambia. He remained a hugely significant political figure in the nationalist movement, rendering support from London in the form of strategic advice, mobilising considerable resources and serving as the crucial link between the African nationalists in Zambia and their backers abroad.

Upon independence in October 1964, the new government led by President Kenneth Kaunda and his United National Independence Party (UNIP) invited Zukas to return to Zambia. Despite running a successful engineering consulting firm in England, he came back to Lusaka and, in a unique manifestation of patriotism, took Zambian citizenship in October 1965. While he was close to Zambia’s political leadership in the First and Second Republics, Zukas devoted much of his time during this period to establishing and leading his engineering consultancy firms. He offered the young country his professional expertise and was responsible for the structural designs and supervision of major public constructions such as Parliament, State Lodge, University of Zambia (UNZA) School of Mines and the flyover bridge on the Great East Road. The UNIP leadership also regularly consulted him on a variety of subjects and his advice was greatly valued. Further national involvement was expressed through his board membership to state institutions such as Industrial Development Corporation, Zambia National Building Society, National Council for Scientific Research and UNZA Council, on which he served from 1966 to 1990.

After his efforts to persuade President Kaunda and UNIP to abandon the one-party state failed, Zukas, like many Zambians, broke ranks with his friends and joined the drive towards multi-party politics. He attended the Garden House Conference that resulted in the creation of the Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD) in July 1990, was elected as the party’s first Vice-National Chairperson at its inaugural convention in February 1991 and played a leading role in the political revolution that followed. In the founding general elections following the re-introduction of multiparty politics, Zukas easily won a parliamentary seat in Sikongo constituency, Western Province. That he, a white Zambian, achieved that feat in one of the country’s most conservative regions, where he had no roots whatsoever, speaks to Zukas’ nationalist credentials as well as his political skill and ability to convince people of the need for change.

Between 1991 and 1996, under President Frederick Chiluba’s government, Zukas held several ministerial positions and history shows that he stood by his principles, was never afraid to speak his mind, and championed the interests of the poor and disadvantaged. He frequently cautioned his colleagues not to lose sight of the reasons why the MMD was formed and had been given an overwhelming mandate by the electorate. Zukas despised political sycophancy and hero-worshipping leaders. He was almost always guided by pragmatism, his conscience and respect for human dignity. Thus, when the Chiluba government passed the 1996 Constitution, which, among other things, barred Kaunda and Lozi Senior Chief Inyambo Yeta from contesting the 1996 general elections, Zukas, as did Dipak Patel, quit his Cabinet position in protest. His resignation signified that there could be civility in politics and that the principle of collective responsibility could not be sustained when the government was doing wrong. He remains one of very few politicians to voluntarily resign their lucrative ministerial positions in the Third Republic, along with Akashambatwa Mbikusita-Lewanika, Baldwin Nkumbula, Ludwig Sondashi, Rodger Chongwe and Vice-President Levy Mwanawasa.

When Chiluba hatched plans, towards the end of his second term, to amend the constitution of Zambia and seek an unconstitutional third term of office, Zukas joined hands with other progressive forces to oppose the President’s bid. He travelled abroad extensively to canvass support for the Oasis Forum, the grouping of civic associations that championed the campaign against the third term. When Chiluba finally succumbed to political pressure and shelved his plans in early 2001, Zukas was among those who formed the Forum for Democracy and Development (FDD) and became its first National Chairperson. He remained active in politics until 2005 when he retired and voluntarily stepped down as FDD chairperson at the age of 80.

Over the past fifteen years, Zukas continued to speak out periodically on matters of national importance, stressing the need to fight corruption, uphold peace, promote national unity, support media freedom, protect democracy, improve the delivery of social services, reduce (rural) poverty, and scale down the high rate of unemployment. More recently, worried about the negative turn that the country took under the leadership of Edgar Lungu, he joined hands with other concerned citizens to form the appropriately named Our Civic Duty Association, an organisation that seeks to foster good governance, encourage effective management of the economy, and serve as a platform for robust discussion of the most salient policy and national issues.

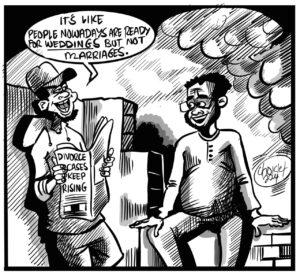

A teetotal non-smoker who exercised daily and a man who was utterly at ease with himself, his personal life spoke of temperance, mental and physical discipline and the presence of an equal partner – Cynthia Robinson, whom he married on 30 January 1954 and with whom he has two sons – that helped him reach such a grand age in an era when lifespans and marriages are increasingly short.

As a genuine and dedicated cadre of progressive change, a defender of principle and the public good, and a porter of a moral power earned from selfless service as a foot soldier for freedom, development, democracy, equality and justice, Zukas evinced true citizenship. Ever on the right side of history, he showed us that to live is a state of continual consciousness. While highly approachable and humble, he held strong political beliefs for which he was prepared to sacrifice privilege. The young generation of political activists should look to his long and distinguished political career for example and inspiration.

In a world in which many are driven to show off not just their wealth and power but also their heroism, the numerous sacrifices they had to make and the grand battles they had to fight, Zukas refused to beat his own drum, repeatedly praising the work of others rather than himself, and he remained extraordinarily modest about his considerable achievements. Zambia has great need of such patriots and active citizens as Zukas, who understand that the essence of life is service. It was as if he was spurred by the words of the Chilean poet and revolutionary, Pablo Neruda, who, in the poem “So is my life” wrote:

“My duty moves along with my song: I am I am not: that is my destiny. I exist not if I do not attend to the pain of those who suffer: they are my pains. For I cannot be without existing for all, for all who are silent and oppressed I come from the people and I sing for them: My poetry is song and punishment. I am told: you belong to darkness. Perhaps, perhaps, but I walk toward the light. I am the man of bread and fish and you will not find me among books But with women and men: They have taught me the infinite”.

May we all attend to the pain of those who suffer, exist for the silent and oppressed, walk towards the light and learn, from Zukas’ life, the infinite! His death represents the end of an epic life. Zukas felt so permanent, as if in his case, and that of a few others such as Kenneth Kaunda and Andrew Sardanis who died earlier this year, death would make an exception. The good thing though is that legends never die; they simply change form and locations.

It remains my conviction that the relevance of death lies in its impact on those that live. Let Zukas’ death inspire us to continually improve ourselves because it is in our quest for individual excellence that we truly become witnesses to the greatness of life and service to humanity. Let such deaths remind us to celebrate the ephemera and gift that each day is, to live now and in the present. We sometimes miss out on life when we seek more, when we seek permanence, for what we have is now, and we must live in the moment. For that is all there is to life – now.