Have you stopped attending the Chakwela Makumbi Traditional Ceremony because they don’t bring bare-breasted girls? Well, you are not the only one. Wynter Kabimba, the former justice minister also hates the fact that there are no fresh titties at the event, and nothing motivates him to attend any more. Yes, he told me all about it in his museum.

I’m sure you have some questions like “Wynter? Museum? Young girls’ breasts? How?”

But before we get ahead of ourselves, let’s start from the Genesis: Kabimba invited my colleague Tenson and I to tour his Museum.

He told us that his house in Lusaka had started looking like a traditional healer’s pad and his wife wasn’t pleased so he decided to establish a museum.

Funny as its conception might be, it was in Kabimba’s museum that I got to learn that our founding father, Dr Kenneth Kaunda, got a ‘tooth job’ at one point in his life which slightly altered his appearance.

It was also in his museum that the concept of nudity intrigued me. What is nudity?

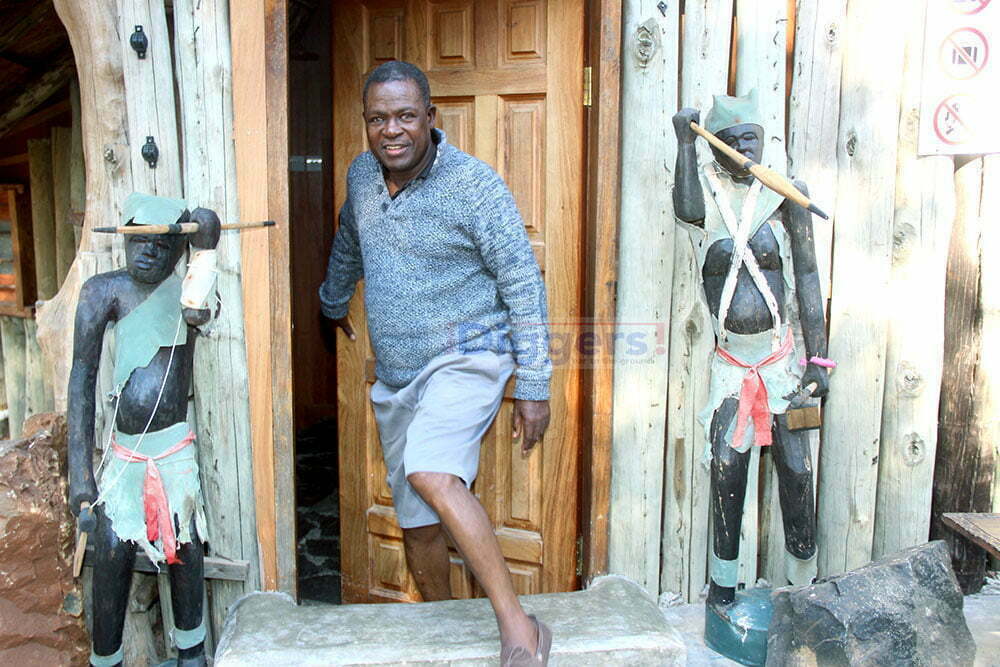

Named after an indigenous tree, Kabimba’s Mutumbi Museum and Art Gallery is set to launch this year and it houses beautiful Zambian sculptures, local artefacts and objects of personal value to him which he has collected over the past 20 years.

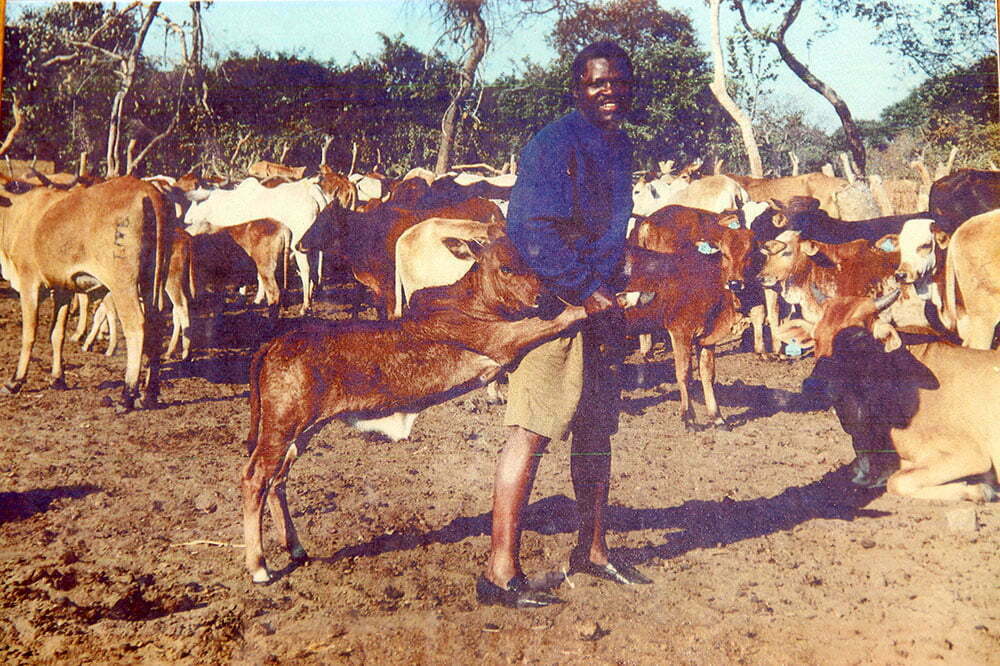

Family values, culture and politics are the underlying themes in this museum and art gallery located on his Mutumbi Ranch in Shibuyunji, about 130 Km from Lusaka, 30 Km before the Blue Lagoon National Park.

What was exciting for my colleague Tenson and I was that our museum docent was Kabimba himself so there was no dull moment. His life stories were both hilarious and teaching.

Where do I even begin? Well, I should probably start from the entrance of this wood and grass-constructed marvel. So, at the entrance was a Luvale chief’s wooden bed the size of a church pew. As if that’s not uncomfortable enough, it also had a wooden in-built pillow! Kabimba joked that Luvale chiefs used to pretend they didn’t need women. But on a serious note, he said he was intrigued by the science behind those beds.

“It was good for your spine. When you have a spinal problem, even now, as part of the physio, the doctors now will advise you to move from your bed and sleep on the hard floor. These guys might not have read it anywhere but it was part of ethnology which is the study of indigenous knowledge of human beings in the community. It’s a single bed so the chief was not allowed to sleep with his wife all the time, don’t ask me how they produced the children,” Kabimba said.

“When they were going hunting, they were not allowed to sleep with their wives for one week. They would sleep on these beds so that they could go out strong. And it was made out of special wood.”

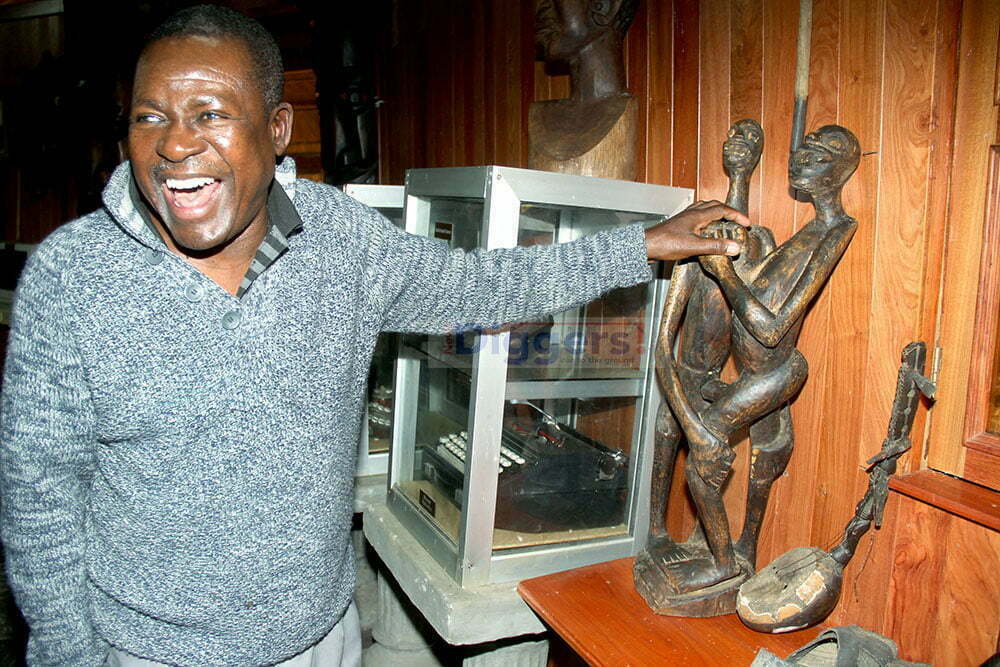

When we entered the museum, we were greeted by nudity, lots and lots of nudity – from sculptures to paintings of bare breasted women, all with one simple label – “Nudity?”

He could tell Tenson and I were a little spooked so he offered an explanation: “I’ve got an interesting theme here which is very culturally conflicting. What does it mean to be naked? Is it exposure of your breasts? Is it touching a ‘pee’ like this guy? Or is it being like this lady? Is it this other lady? What does it mean for you to be naked?”

As you can imagine, I was laughing uncontrollably by now, but he was asking valid questions. He continued: “So nakedness actually, is defined by the culture in which you are. So you give this to a white fellow, this lady is naked but this one is not naked. So I said to myself, what is nudity? So when you have NGOCC go to [Chieftainess] Nkomeshya to say ‘we don’t want those young ladies to be dancing with their breasts out because that is nakedness’, then I said to myself, which definition are you using? Are you using the western definition or the Zambian definition? Because in Zambia, a woman’s breast or a woman’s breast is not nakedness, unless ali na vibelo (unless she leaves her thighs out). I want someone to answer that question, what does it mean to be naked?”

He also confessed that he was against Senior Chief Mpezeni’s decision to bar bare-breasted women at the Nc’wala.

“I was against it! Even ba Nkomeshya, I stopped attending that traditional ceremony of hers. I told her it is no longer a traditional ceremony for me. What took me there was to go and see nice breasts of young girls. Now if you are going to cover them, why should I come there? It is no longer tradition,” Kabimba said.

“I protested, I said I should go to the Nc’wala? To go and see what? You are covering up tradition and culture, I don’t want to go there.”

He told us he was impressed with how far Swazis were willing to go to preserve their culture.

“I read a story in the Mail and Guardian. A group of young ladies at Johannesburg University decided to come together and form a cultural society and one day, they went out on the streets to practice the Impi dance, bare breasted. But Google decided to block those photos and then wrote a statement that ‘these pictures are not in conformity with our community values’. So these girls said ‘which community are you talking about? Why are you judging us against your community?’ And they actually went and staged a protest before the Google office in South Africa to reinstate the pictures but Google stuck to its guns,” Kabimba narrated.

“So the problem here in Africa is that the media is controlled by the West. It is still part of the colonial hang over, the perpetration of neo-colonialism. It’s used to manipulate our minds so that we believe in what one society believes in, and not our society. So what is nudity? One day, I had to tell my mother, ‘please, remove your head wrap, let me see your head’.”

We had a good laugh before moving on to something more sentimental.

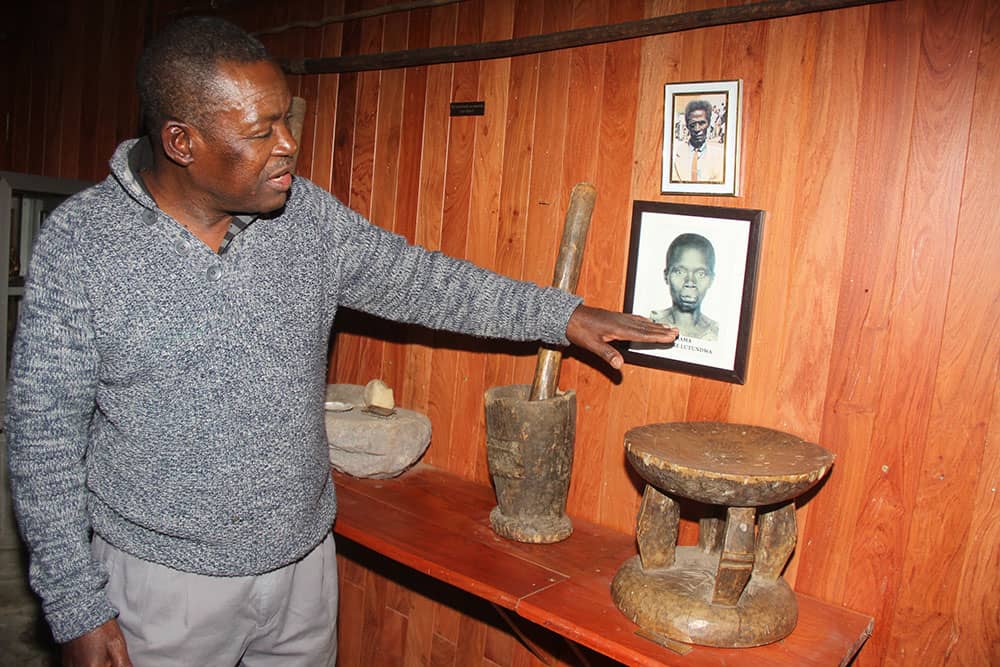

He showed us a picture of his maternal grandmother and above it was a picture of his uncle. Kabimba explained that his uncle had lost his eyesight but regardless of this, he managed to carve out a motor (kabende) and pestle for his grandmother, demonstrating that skill lay in the mind, not in one’s sight.

“One day, he went to visit my mother and he heard her asking him to go and ask for a kabende from a neighbour. So he was surprised and he promised to make one for her. Three weeks later, we saw him coming, carrying this (kabende) and being led by one of his kids. He made this, blind! So the question that I ask is: where does your skill lie? Is it in your sight or is it in your mind? Which shows you that the skill that you have is actually in your mind, it is not in your sight,” Kabimba explains.

He then went on to show us a picture he re-printed and framed from an edition of The Post newspaper. It was a picture of a man on a canoe with his wife, three dogs and all their valuable possessions.

“This picture means a lot to me. It was the year of floods in Western Province so this guy was moving away from the flood to the highland. So I said to myself, as you and I worry about stove, fridge, microwave and whatever, this is all that this guy has. A wife, three dogs and himself and this is what was important for him to save from the floods. It has meaning in terms of life in the village,” Kabimba explained, after which he showed us a grinding sledge which was used to grind millet in the olden days, a snail shell used as a spoon and more recent items like Record Players, VCRS, and phone receivers.

There were also some Luvale cultural masks, beads and other artifacts. Kabimba confessed that as a young boy, he would skip school to follow the Makishi dancers.

“I went to school in Livingstone and if there was anything that mesmerised me during that period were the Makishi. And if I am walking to school and I meet the Makishi along the way, I will not go to school, I will just follow them, just to watch, they just fascinated me. When I got back home, my mum would look at my feet and say ‘iwe, siu na yende ku skulu (you didn’t go to school)’ because of the dust. I would not realise that the dust would give me away,” he recalled.

“It was not forbidden to follow them. Where you were forbidden to go is the Mukanda, the seclusion where they do the circumcision. There if they found you those days, they’d actually kill you. We used to have friends who we used to play with and we just saw the guy disappear. When you go to their house and ask for them, they just tell you, ‘he is not here’. You go back a few more times, they tell you the same thing. Then when I ask my mother, she’d just say ‘he went to Mukanda’. You are not even visited by your mother and father until you come out.”

Just as we were about to turn a corner, there they were: two pictures side-by-side showing how our beloved KK’s face underwent a tremendous transformation when he fixed his teeth. Amazing!

“These two photos are very interesting, these are KK’s photos. This is KK’s original face and set of teeth. What he has now is artificial. You can see that they are like two different human beings but it is the same person, just the set of teeth changed his face. I got these from ZANIS,” Kabimba said, showing us a contrast between KK’s wide smile we all love and a younger him with a longer face.

I better stop with highlighting these artefacts now, it’s not like he paid us for advertising, LOL!

But I thought, what does it take to own a museum? And apparently, anyone can have a museum because there seems to be no regulation.

“I looked at the law, National Heritage Act, the Museum Act which prohibit the establishment of a private museum. But I still went ahead and wrote to the National Heritage Commission just in case I’ve missed some amendments to the law. After a week, the National Heritage Commission wrote to me that in fact, my letter should have been directed to the Director of Museums and they were kind enough to say they had redirected my letter to the Director of National Museums and that I would hear from them. I didn’t get any response from them so I just proceeded,” he said.

To sum up what he was trying to achieve with his museum, Kabimba said it was simply an expression of his struggle to preserve his culture and stay true to his roots.

“The national museum is supposed to put together different components of our culture so that our country doesn’t lose them. The fear I have, and what has prompted me to do this at a private level is that I want to make a contribution to the preservation of my cultural heritage in order to bequeath an identity on future generations, which identity is getting eroded very quickly. Right now, people think it is civilisation for our children to speak only English and not the local language but what that is actually identity suicide,” said Kabimba.

“I am also trying to contrast traditional life and modern life, what we call civilisation. And my own argument is that my traditional life was probably more civilised than the so called civilised life. There is a phrase that history favors the writer. We are inculcated by these theories that what the West has brought is what is civilisation because they are the ones writing the history. I want to write my own history through archiving a collection like this. It is sad that the government has no clear policy to preserve culture. Their understanding of culture is limited to traditional ceremonies, that is not what culture is.”

I could go on sharing other interesting things about this Museum and Kabimba’s Ranch but my boss, Joseph, won’t spare me anymore space. He calls me a ‘lembist’ and this is all I could share in the space I solicited for.

Oh, and Kabimba is building a lodge on his ranch so once complete, this will definitely be a one stop spot for all things nature and culture.

2 Responses

Interesting to know that there people who are keeping our culture, keep it up Wynter!

Very interesting article.