Honourable Dora Siliya, the Chief Government Spokesperson, says President Edgar Lungu has conceded that there is a serious problem with procurement system, which is allowing inflated bids and thereby permitting “legal corruption” through the normal tender procedures. This is very thought provoking and confusing to some people who wonder how corruption could be regarded as ‘legal’.

We understand exactly what the Minister means, but we disagree with her solution. Honourable Siliya is blaming the occurrence of the so-called legal corruption on junior procurement officers whom she says lack supervision from a senior overseer in government, but we beg to differ. Today, we will start by showing the Minister how she and her fellow Cabinet Ministers are involved in corruption, all the way up to the President himself, long before the procurement committee sits to evaluate bids.

For a very long time now, we have been saying that there is grand-scale corruption through government public tenders. In particular, procurement of fuel, oil, fertilizers, fire tenders and infrastructure projects are where there has been and continues to be massive procurement of notoriety and fraud. It is shocking that this realization has come so late to President Lungu, while tens of millions of dollars have been spirited away by unscrupulous businessmen.

It is public knowledge that the fertilizer tenders for the 2015-2016 farming season were inflated by millions of dollars, and documentary evidence was published in various media. This was ignored by the investigative agencies, as was evidence for fuel and oil procurement. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been spent in the past few years by the defense and security agencies and to-date, no public tender notice has ever been issued. In public interest, these defense procurements also merit an investigation.

It is our opinion that if we develop an impermeable procurement system in our government, no single private company would succeed to siphon public resources using corruptly awarded tenders. When analyzing corruption in the procurement system, it is the giver who should be of greater concern and not so much the taker. Companies are registered to make profit, the bigger the profit margin, the better for them. No wonder we see foreign companies coming to Zambia to win lucrative contracts like installing traffic surveillance systems and depositing speed fines in their private accounts, when we have learned technocrats and engineers in our own government who can do the job.

We should not throw the blame on the supplying companies in such transactions. The person we should take to task, as a nation, is the controlling officer. Why does our procurement system need middlemen to facilitate the purchase of basic goods and services? That is why procurement officers are among the most admired civil servants in government. They don’t get broke, if they do, it’s because a payment has delayed somewhere.

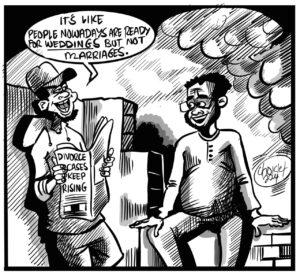

What is worse is that a poor country like Zambia has the luxury of embracing the tendering system that recognizes the ‘best’ evaluated bid and not the lowest evaluated bid. That is why the public is crying about the US $42 million paid to GrandView for the supply of 42 fire trucks; that is why the public is outraged with the US $273 million Star Times contract for Digital Migration and the US$1.2 billion deal with China Jiangxi for the construction of the Lusaka-Ndola dual carriageway.

What people do not understand is that even if these companies doubled their bid offers and the controlling officer sees that as the ‘best’ evaluated bid (for whatever underhand reason), then they commit no crime in awarding the contract. This is the legal corruption that Honourable Siliya was referring to. Critics can call these companies all sorts of names, but in the absence of proof that there was corruption involved, it’s a dirty, but legal game, as long as the process was followed.

That is why the lowest bidders don’t win contracts in this country; such bids leave very little spoils to share between the middleman and the procurement wolves. In fact, lowest bids are considered a risk. So, if you ask those who are in the business of supplying to our government, they will tell you that you must never be the lowest bidder. If you have an inside connection to facilitate the awarding of the contract, you just have to beat the price of one or two suppliers to avoid public outcry; stay in the middle and you are in business.

Surely, we must move away from that bidding system and embrace the lowest-evaluated bidding system because we are such a poor country. At least there must be a cap where we say, ‘if anyone bids above this price for fire trucks, they will not be considered.’ We must be realistic and get rid of this luxury in the procurement system if we are serious about fighting corruption. If the lowest bidder has the capacity to deliver but has a few grey areas in the bid, the procurement team must be able to approach such a company and say “we have identified you for this job, but work on this and that”.

This will promote genuine competition among supply companies to serve the country better. But the problem we have in Zambia is that big companies that sponsor political parties during election campaigns become too powerful and arrogant. They hold the Executive to ransom, as they demand to recoup their campaign spending – leading to State capture, especially if the President is weak, as is the case currently.

In our current scenario, big companies don’t struggle to get government contracts because the system does it for them. Sometimes Permanent Secretaries put together teams of procurement officers who prepare bid documents for friends of the President. They make sure that their paperwork is flawless and the figures sit on the right end of the evaluation scale.

We need these tenderpreneurs to be regulated; they should be subjected to transparent tender processes and awarded government contracts on merit. It has to start from the Head of State telling those businessmen who put him in power that they will not get government contracts on a silver plate. They will have to beat their rivals through competitive pricing. No Zambian would complain if that were the case.

But we have such a rotten procurement system where the Head of State demands for commission even before a contract is awarded. Under fuel procurement, no individual company can win a tender in Zambia without paying what they ironically call “Due Diligence” to State House. This is the reason why fuel prices will never go down, and we cannot entirely blame the suppliers. You find the President is the one who advises the supplier to put a markup on their tender price so that he gets his heavy kickback from the deal; then the minister adjusts the price further up before the permanent secretary and the rest of the procurement officers join in to secure their cuts.

This is where the problem is. This legal corruption is well sponsored by the highest powers that be – the politicians, and they know it. So, it shocks us that the Chief Government Spokesperson and her President could pretend to identify this serious problem now, and then suggest a clumsy solution like establishing a much senior overseer position in the procurement departments of government. What procurement position can you create which will be more powerful to reject directives from the President and his ministers?

In fact, in our next edition, we will show how powerless procurement officers are, and how permanent secretaries cannot authorize the awarding of contracts without approval from the Minister and State House in some cases.