Market access has a pull and push effect on livestock production. There is no doubt that the Saudi Arabian market expectation has already started pushing up the goat production in Zambia with the number of emerging farmers (middle-income earners) engaging in goat production.

However, some questions still come up in farmers’ minds. Among other questions are:

1. Can Zambia afford to export one million goats a month?

2. Does Zambia meet the standards of the Saudi Arabian goat market?

3. Are we free of diseases that may pose a risk to the Saudi Arabian goat trade?

4. Since more than 80% of the goat trade is informal (IAPRI, 2017), who will participate in this export market? Will it be the farmer, intermediaries or private agro-food companies? Who are we empowering? Is the Saudi Arabian export market pro-poor?

5. The price that has been thrown around and which has got the farmers excited is Cost, Insurance and Freight (CIF) to Saudi Arabia. Will the farmers in Zambia afford logistics?

6. Which port will Zambia use to export the live goats? Dar-salaam or Walvis Bay? Or maybe via cargo planes? Are we going to compete with countries in the horn of Africa favourably?

7. Are we negotiating for export of goat meat so that we develop our goat value chain? If so, do we understand that Saudi Arabia has a high Islamic population? Thus the biggest constraints for the market are strict quality checks and phytosanitary norms, along with Halal requirements?

Processes, such as stunning and automated mechanical slaughter, do not accommodate Halal procedures, making these methods of slaughter unsuitable for the region. If Saudi Arabia was to accept this offer (which is unlikely), do we have facilities?

8. The fact that Zambia is landlocked, Is the cost of exporting to Saudi Arabia cheaper than that of the regional market? For instance, the Democratic Republic of Congo. Has the government conducted a cost-benefit analysis as they are preparing for this market?

9. Who will meet the transaction costs for export? These will include costs like bulking of goats from different parts of Zambia, quarantine, animal health management, transport to the port of origin, veterinary costs for the veterinarian accompanying the live goats to the port of destination, conformity assessments, insurance, etcetera. Note that, the final price of a goat at the point of destination is the total of expenses of several intermediate steps.

To answer some of these questions, let us briefly understand the Saudi Arabian livestock market, the trends in the countries (major exporters) that are currently exporting goats and sheep to Saudi Arabia, what it takes to export livestock, and what Zambia should start doing in preparation for this high-value market.

Arabian livestock market

Saudi Arabia has a population of about 32 million people (World Bank, 2016). Strong economic and population growth are the major drivers of increased consumption of meat in Saudi Arabia. Due to its location and lack of natural resources necessary for livestock production, most of Saudi Arabia’s edible meat is imported, to meet its domestic demand. Currently, Saudi Arabia can meet only 56% of its edible meat demand, i.e., chicken, beef, goat and sheep, with domestic supplies (Mordor Intelligence, 2017). Most of the live goat and sheep imports are from Somalia/Somaliland and Australia. High volumes of goats and sheep are imported during Eidul-Adha, or feast of sacrifice in commemoration of the prophet Abraham. During this time, almost every family slaughters a four-legged animal, mostly goat and sheep.

Trends in top countries currently exporting goats and sheep to Saudi Arabia

In 1990, Saudi Arabia banned the import of sheep from Australia due to a disease called scabby mouth (Orf) and quality. Orf is a viral disease which is transmissible between animals and humans. We have scabby mouth (Orf) in Zambia, and no vaccinations are currently being conducted (Simulundu et al. 2017). The ban was lifted in 2000 with strict animal health, age requirements, proper trace back and animal management system. At the same time, Australia could not meet the demanded number of goats due to a limited number in the country.

Similarly, Saudi Arabian banned the import of sheep and goats from Somali/Somaliland in 2000 due to an outbreak of a disease called Rift Valley Fever (a mosquito-borne disease which affects both animals and humans). There is the possibility of the presence of Rift Valley Fever in Zambia although there is no scientific evidence (Dautu, 2012). The import ban affected exports caused significant economic and trade loss. The ban was lifted in 2009. Since 2011, the country has gone on recovery with major improvements in infrastructure. In their quest to entirely formalise the goat and sheep value chains, the Somali government banned the slaughter anywhere apart from abattoirs in 2013.

However, Saudi Arabia again banned the Somali livestock imports in September 2016 following reports of an outbreak of Rift Valley Fever in the Horn of Africa country but lifted the ban within a year.

What does it take to export livestock to a country like Saudi Arabia?

Sheep and goats are collected from different parts of the country by a trader who has sourced for the export market. They are then bulked (quarantined), and all animals are vaccinated, dewormed, and de-ticked a few weeks before export. For Saudi Arabia, the animals must be disease free and weigh between 25-40kg. The importing country (Saudi Arabia) may decide the accredited laboratory that must screen the animals against diseases and issue an international health certificate. It is a requirement that animals have to be at the port two weeks before departure and fed on feed that they will eat on the ship at least a week before they come to the port of departure, meaning that they have to be quarantined at least for 21 days. All paperwork and export requirements are done during the time that animals are in quarantine, sent to the importing country which then authorises the export once all conditions stipulated in the import permit are met. A veterinarian accompanies animals to the port of destination with maximum attention to the animals on the ship. The veterinarian from the country of destination will conduct inspections, and if the animals pose a low risk to the goat and sheep trade in the country, they are allowed. It is important to be aware that during this quarantine period, some animals die due to inanition, and the exporter will meet the cost of dead animals.

Self-assessment

During the ZNBC TV1 main news on 7th September 2018, the Minister of Fisheries and Livestock, Honourable Kampamba Mulenga revealed that President Edgar Lungu will flag off the export of goats to Saudi Arabia next month following the completion of an import needs assessment that was carried out by the Saudi Arabian Government (https://www.znbc.co.zm/ecl-to-flag-off-goats-export/).

Looking at the facts presented thus far, are we ready for the export? Will this be sustainable? In my opinion, certainly not, until some measures are put in place to formalise the goat market in Zambia. The additional costs of putting these measures in place might be more than the profit arising from the export market. However, until a systematic economic evaluation (partial budget analysis) is conducted on the Zambian goat enterprise, the lucrativeness of the Saudi Arabian export market remains speculative. Zambia should rather concentrate on formalising the goat and sheep value chain and exploit the lucrative regional market before embarking on this long journey. A case in point is the failed creation of disease-free zones with the view of exporting beef to the European Union market. Do we want to repeat the same mistake? There is potential in the regional market. But are we sure we have met the local demand before we export?

What should Zambia do to prepare for the Saudi Arabian export market adequately?

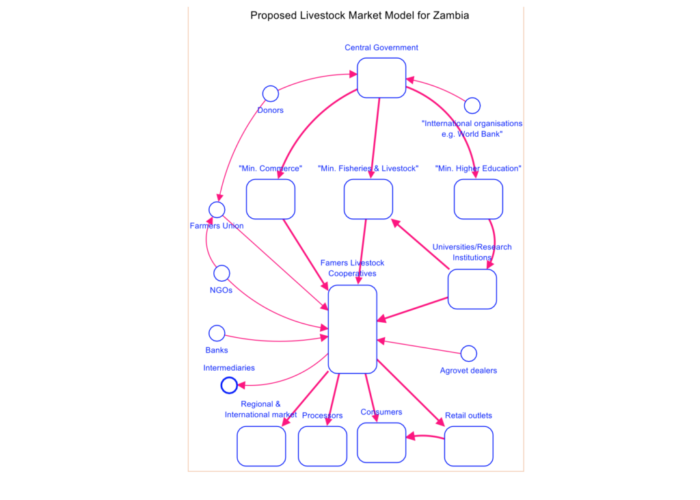

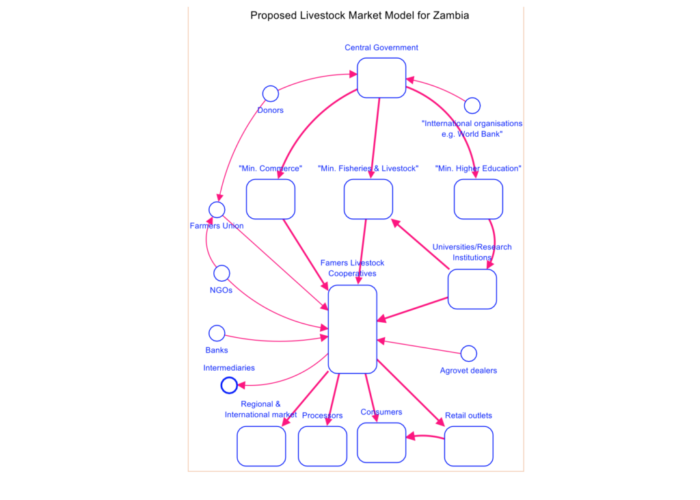

Since the goat and sheep market is mostly informal, the government and stakeholders must start by formalising it through a cooperative market model. This can be achieved by organising farmers in cooperatives (bulking centres) just as is the case for smallholder dairy farming in Zambia. These cooperatives must be run by the farmers with the government only playing the market or value chain governance role (policy and technical guidance). The cooperatives must run as market hubs where all activities such as training in production technologies, business management, research and innovation, animal health management, extension services, feedlots, butchering, buying and selling of live goat/sheep and other small livestock etcetera will be conducted. Some of the advantages of cooperatives include risk pooling, bargaining power, easy access to finance and centre of excellence. The Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock, with the engagement of stakeholders, MUST quickly develop the livestock policy to facilitate livestock market models such as the one in the figure below. Currently, the Second National Agricultural Policy (SNAP, 2016) attempts to address the livestock aspects, but there is a need for a strategy to operationalise the objectives already set in the policy, as we develop a nexus livestock policy.

to facilitate livestock market models such as the one in the figure below. Currently, the Second National Agricultural Policy (SNAP, 2016) attempts to address the livestock aspects, but there is a need for a strategy to operationalise the objectives already set in the policy, as we develop a nexus livestock policy.

One Response

Nice, clear, and deatailed insight of the saud arabia goat market opportunity in Zambia