Since the adoption of the Non-Governmental Organisations Act in 2009, the question of a regulatory regime for NGOs has plagued successive governments. On the one hand civil society actors demand an enabling regime which respects the full scope of the freedom of association, on the other hand the state insists that NGOs must lead by example and reflect the transparency and accountability they so fervently champion. The result? Nearly 2 decades of consultation, negotiation and drafting. Zambia’s Parliament is currently considering a Non-governmental Organisation’s Bill (the NGO Bill), the latest attempt to repeal and replace the current NGO Act.

For many ordinary citizens the operations of NGOs are shrouded in mystery. For others, NGOs are synonymous with the watchdog role that many have come to rely on from civil society. NGOs, the NGO Bill and whether NGOs are regulated would therefore appear to be a problem for a select few Zambians. This is far from the case. In developing nations like ours, NGOs are key development partners working across various sectors from health to education; empowering marginalised communities such as children, women and persons with disabilities; and providing vital services to the remotest parts of our country. In recent times, NGOs have emerged as a vital stakeholder in our democracy, providing an independent voice on behalf of citizens on governance issues and championing human rights. NGOs are defined very broadly under the Bill as a private voluntary group of individuals or associations, excluding those pursuing partisan politics, which organise themselves for the promotion of civic education, advocacy, human rights, social welfare, health, the environment, charity, research or other activity or program for the benefit of the public. The regulation of NGOs is therefore everyone’s business.

After several years of dialogue on the question ‘what is the best way to regulate NGOs?’, we are hardly any closer to consensus. The regulation of NGOs is both complex and context-dependent, there is no one-size-fits-all answer. International and regional best practice emphasizes the need for laws to encourage rather than restrict the establishment of associations such as NGOs including through clear and simple registration processes, limited intervention into their operations and the freedom to seek and receive funding. The current NGO Bill seeks to address some of the concerns from the 2009 Act. It addresses the issues of registration, oversight, coordination and self-regulation of NGOs. However, in many respects, the current NGO Bill falls short of international and regional standards.

With regard to registration, the NGO Bill proposes that in addition to registering, NGOs who wish to operate in Zambia must also obtain licenses. These licenses attract an annual fee and are to be renewed every 5 years. The requirement for a license in addition to registration creates additional financial and procedural barriers to operation for small and rural organisations which operate at grassroots level with limited access to resources. There has been no reason given as to why an additional licensing requirement is being proposed or what issue this licensing seeks to address.

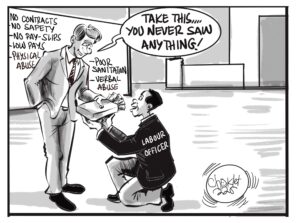

Oversight over the activities of NGOs forms a large part of the Bill. The Bill establishes a Department of NGOs which is under the “general direction” of the Permanent Secretary of the ministry responsible for community development and social services. The functions of the Department include providing guidance to NGOs on how to harmonise their activities with the national development plan and facilitating access to funding. The Bill further introduces “inspectors” of undefined qualifications who will have the power, with a warrant, to enter any premises on which they have reasonable grounds to believe an offence is being committed and search the premises and anyone on those premises and take extracts of documents. A person who ‘delays’ or ‘obstructs’ an inspector in the performance of these functions can be imprisoned for up to 3 years. These provisions should be cause for great concern to all citizens for several reasons.

Firstly, the freedom of association, which is guaranteed in Article 21 of the Constitution, means the freedom to undertake activities of ones choosing, jointly or individually within the law without unjustified interference from the state. While the national development plan is an aspirational document, it should not be used to limit the activities that NGOs can undertake. Secondly, if NGOs are to be independent, the ‘facilitation’ of access to funding greatly undermines this independence. Thirdly, the powers of search and seizure in the interest of preventing crime are already legally performed by qualified law enforcement personnel. There is no justification for giving such powers to persons of unclear qualification with limited judicial oversight.

It is worth noting that NGOs are not opposing regulation for the sake of opposing it. However, when statutory regulation is adopted, it should be developed and applied from the standpoint of creating an environment which legally, politically and financially enables civil society by allowing NGOs to form freely, operate independently, and contribute meaningfully to public life. The adoption of such regulation ought to be preceded by a transparent legislative process informed by broad-based meaningful consultation given the wide range of areas of work which NGOs in Zambia are involved.

At the core of an enabling environment for NGOs is respect for fundamental rights, freedom of association, expression, and assembly, as well as the state’s duty to refrain from unjustified or excessive interference in NGO affairs. In practical terms, this means that laws governing NGO registration should be simple, transparent, one-time event. NGOs should be able to freely undertake activities of their choosing within the limits of the law without political interference, and access resources, whether domestic or international, without undue restrictions. Oversight mechanisms should be fair, proportionate to the size and nature of the organisation, and designed to promote good governance rather than control. An enabling framework ought also to provide incentives for NGOs which are development partners and fill gaps in the provision of services.

Chapter One Foundation is a civil society organisation that protects and promotes human rights, constitutionalism, rule of law, and social justice in Zambia. Please follow us on Facebook and LinkedIn under the page ‘Chapter One Foundation’ and on X and Instagram @CofZambia. You may also email us at [email protected].