This feature makes an argument that lost COVID-19 window of opportunity for Zambian farmers should help us to reflect on what has gone wrong in Zambian food systems – reliant on inflows from regional countries – and wider support for smallholder agriculture – politically inclined and suffering from what can be described as short termism. I call for long-term view of agricultural support and development of national food systems.

Political statements of the previous regime set the tone for COVID-19 policy responses and agricultural activities in Zambia. These statements advanced a gradual but conscious facilitation of continued economic activities amid the pandemic. A full lock down, it was feared was going to affect revenue flow for the government, ability to pay salaries and social cash transfer. There were concerns about delivery of inputs and wider agricultural activities that could have affected livelihoods and national food security. State actors used this to argue that COVID-19 presented a new window of opportunity for small to medium scale farmers to produce/sell their products to chain stores that for a long time have denied them business and opted for foreign products. Chain stores should, the argument went, prioritise local agro products in their localities and that only products that could not be sourced from locals should be imported. One immediate move was to ban importation of onions, but failure for local producers to meet demand compelled the government to lift the ban few weeks later.

Recent research within the Centre for Trade Policy and Development has shown that disruptions in regional supply chains such as Zimbabwe and South Africa did not present any transformative opportunities for local farmers. It is clear in our research that national policy statements did not automatically translate into production and market responses by local producers. We ask: What are the reasons behind this and what can we learn from this dynamic?

Our research reveals four important lessons underpinning lost opportunities for local farmers. First is policy fluctuations which affected price transmission but also stability of markets. For instance, a 2021 report by Lusaka Times shows that on 10 February 2021, the Government of Zambia banned the importation of onions (Lusaka Times, 2021). This ban was aimed at presenting an opportunity to local producers to capitalize on supplying the onions. Interestingly, a month later on 26 March 2021, there are reports that the government reversed this ban, arguing that local producers failed to meet the demand. The lifting of the ban allowed 100,000Metric tonnes (Mt) of onions into the country as a move to ‘normalize prices of onions.’ Little debate ensued on how to address the deficit in the short-term. Ignored also was how the country have boosted production to meet market demand. Was there really a shortage of onion supply in the country? Was it a question of production (availability) or question of access? What about quality and product specification issues vis a vis chain stores and other off takers? These are questions for policy but also for producers.

Second is the issue of smallholder capacity. Since independence, successful governments have followed maize-centric policies and support towards agriculture has unfortunately narrowly been viewed that way. Agricultural support in Zambia has largely revolved around food security, only now are measures aimed at broadening value chain support emerging. COVID-19 exposed this gap as producers failed to garner enough quantities or failed to meet specific specifications. This is reflective of historical interventions that failed to see agriculture in its broader sense beyond food security.

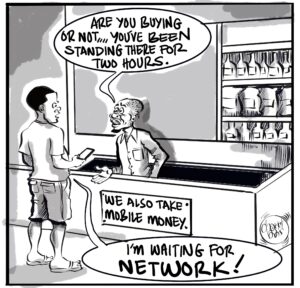

Third is the question of infrastructure. More broadly, in Zambia (as with other countries across sub-Saharan Africa) infrastructure deficiencies are typically framed in terms of a “financing gap” in need of private capital. There are issues around transport infrastructure, with some producers poorly linked to markets. COVID-19 containment measures did not help rural producers and in many cases did not emphasise safe trading. One consequence of this relates to a fourth component on unclear market linkages. As far as we know, there has been no mapping of how different agro-ecological zones in Zambia could be linked to what markets. This potential disjoint is a major issue facing local producers. There is potential here for interventions to explore and understand dynamics related to territorial markets or prospects for collective marketing and bulking centres. These gaps have been laid bear with COVID-19.

COVID-19 pandemic has exposed fragilities in Zambia food systems at different levels. It is time to reflect and think carefully about our future sources of food, who producers and for which markets. There is need to think beyond the COVID-19 gaze here and plan with a long-term perspective beyond traditional silos. The materiality of specific agriculture produce mean farmers cannot automatically respond to market demands – and here lies the point. The current government has ambitiously increased Community Development Fund (CDF). Whereas it is too early to explore and understand impacts, CDF, we contend, can be deployed in such a way as to build regional competitiveness. Constituencies can explore potential of joint infrastructure projects that can aim to build regional trade competitiveness and enhance wealth accumulation for the locals. There is scope for innovation here but actual realities might be more complicated than we might think.

Dr Simon Manda is Non-Visiting Senior Research at the Centre for Trade Policy and Development under the Trade and Development Desk.

Email: [email protected].