Chilufya Chanda had very high expectations of life after his studies at the tumultuous University of Zambia. Working in a video arcade sandwiched between bars in Lusaka’s sprawling Garden compound was not one of them. Chanda 33, is a holder of a bachelor’s degree in English and Literature and is supposed to be teaching in a secondary school, but he has been job hunting for over 8 years. Chanda is now resigned to his predicament.

“Mudala (old man), all my hope is gone,” laments Chanda. “Things are worsened by the fact that when government starts recruiting teachers there is no system that is followed.

“I’m just thinking they should have a plan on how the recruitment should be done,” he said. “Why should people who graduated in 2010 be asked to apply at the same time with 2015 graduates… is it fair?” Chanda thinks this is not proper and it is causing many graduates to wait for years to get absorbed. “I think a systematic way should be created,” he said.

“Now I hear there’s a new way of applying they have introduced. The Teaching Service Commission has advertised 2000 positions, I can bet more than 8000 people will apply. “Worse they are now asking applicants to pay K570 (about $58US dollars) registration fee before they apply, our own government has turned into an employment agency” Chanda said with a sigh of despair.

Of Zambia’s estimated 16 million population, about 800,000 people are in formal employment while over 2 million are said to subsist in the informal sector holding jobs that pay below the minimum living wage. According to the Central Statistics Office (CSO) employment figures for September 2017, Zambia has slightly over 12 million people in the working age group representing almost 75 per cent of the population.

Zambia’s employment situation reached crisis point in the mid-1990s when the state with the advice of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), was forced to sale off state owned enterprises in order for the country to receive balance of payment support.

The view of the two multilateral institutions at that time was that state-owned enterprises were inefficient and were shielded from competition.

As a result of the privatisation program, hundreds of Zambians working for state enterprises ranging from mining to tourism, lost their jobs many have never been compensated to this day. Consequently, poverty levels and unemployment levels went up resulting in the country losing its middle-income status. Government is not sitting idle. President Edgar Lungu recently announced government plans to create over 1 million jobs through the newly created state company Industrial Development Corporation (IDC).

President Lungu said his government intends to use growth areas of agriculture, tourism, infrastructure, manufacturing and information and communication technology. Government plans to list state owned enterprises on the Lusaka Stock Exchange so as to ensure citizens are economically empowered.

“We want to stimulate job creation, and as government we will create an industrial policy, for industrialisation and job creation agenda, mining will continue to play a key role,” said President Lungu at the opening of parliament.

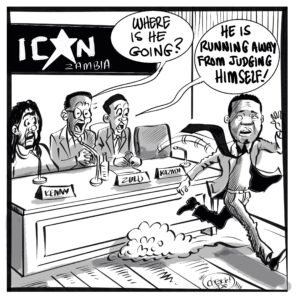

Such an investment agenda demands upholding good governance which underpins investor confidence and flourishing of private-business. It is therefore doubtful how President Lungu and his government will be able to create these jobs in the wake of poor governance, characterised by abuse of human rights, lack of freedom of association, dwindling government revenue, lack of press freedom and a general drop in investor confidence. Coupled to the foregoing, the judiciary seems not to operate independently.

Alex Vines of British think-tank Chatham House argues why good business can never flourish under poor governance. “Economic growth on its own is not enough. Business, especially good business, will not flourish under poor governance. Likewise, state-building is tied to business, via the key linkage of tax – central to the social contract between people and their government, and a driver of accountability,” notes Dr. Vines.

In his September 2017 study dubbed Size Matters: Developing Businesses of Scale in Sub-Saharan Africa that focused on Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia, Dr. Vines urged Africa’s policymakers to formulate policies that will help promote growth of companies and create better jobs. He said it was important that Africa’s policymakers understood drivers and obstacles to growth of companies if they were to create jobs for the continent’s youthful population.

Africa’s young people like Chanda have very high expectations and their governments have the responsibility to meet these expectations if they are to stop undertaking perilous journeys across the Sahara Desert in-order to seek opportunities in Europe.