NAREP president Elias Chipimo has insisted that President Edgar Lungu abused his office when he accepted land as a gift in eSwatini as it was given to him in his official capacity.

On Tuesday, the Council of the Law Association of Zambia issued a contradictory statement on the subject matter; whilst maintaining that the Head of State did not breach any law, LAZ asked the Head of State to relinquish his gift without explaining why and how they arrived at this conclusion.

But in a letter addressed to LAZ president Eddie Mwitwa, Wednesday, Chipimo noted that the legal body’s statement was concerning as it failed to answer the right question about the whole saga.

Chipimo told LAZ that it was the mere act of receiving a gift whilst on official duty which constituted ‘abuse of office’ and therefore translated into corruption.

He stated that the question to ask was “Did he or did he not receive the eSwatini land in the course of the performance of his official functions”? and not: “Did he abuse his office before accepting the gift”.

Below is Chipimo’s full letter to LAZ:

Dear President Mwitwa,

Receipt of a gift by the Republican President and Section 21(1)(b) of the Anti-Corruption Act

I refer to the official statement issued yesterday by the Council of the Law Association of Zambia (LAZ) regarding the controversial acceptance of a purported gift of land in eSwatini by the Republican president, Mr. Edgar Chagwa Lungu. As an Opposition leader, I am concerned that our Head of State and Government can receive monumental gifts from foreign Heads of State while acting in his official capacity and there is only timid and fawning public debate about such a development. The whole event is particularly troubling given the shifting explanations as to what actually happened and in whose name the title of the land was held at the time of its gifting.

Having reviewed the statement you issued, I am concerned that the LAZ opinion demonstrates two errors:

(a) in referencing Article 266 of the amended Republican Constitution as part of the rationale in determining whether the Republican President is a “public officer”; and

(b) in arguing that the mere receipt of a gift by the Republican President in and of itself does not constitute a breach of Section 21(1)(b) of the Anti-Corruption Act, especially in the absence of any evidence that the receipt of the gift was preceded by either:

(i) some abuse or “corrupt element”; and

(ii) evidence that the acceptance was unreasonable or in some way prejudicial to the nation.

Let me address each of these issues.

Does the definition of “public officer” include the Republican President?

Although you draw the conclusion that the Republican President is indeed a “public officer” and therefore subject to the provisions of the Anti-Corruption Act, your argument is couched in somewhat speculative terms and does not appear to be grounded on the correct legal source. In pointing to Article 266 of the amended Republican Constitution, you run the risk of muddying the waters of interpretation and allow some doubt to enter the path to your conclusion. There is a more straightforward answer to the public officer conundrum:

– The amended Republican Constitution defines the term “public officer” for the purposes of interpretation of that Constitution and not as a general definition to be applied to all statutes while the specific definition of public officer in the Anti-Corruption Commission Act is exclusively for the purpose of determining whom this specific statute in intended to regulate.

– In fact, Article 266 of the amended Republican Constitution starts with the words: “In this constitution” confirming that the terms defined are purely for purposes of interpreting the provisions within the constitution and not in any other law.

– This is made abundantly clear by the fact that the term “public officer” under the pre-amended Republican Constitution does not include and unpaid public official whereas in the Anti-Corruption Act – which was passed long after the pre-Amended Republican Constitution – includes both paid and unpaid public officials.

– The definition of public officer under the Anti-Corruption Act includes any person employed in the service of Government, whether appointed or elected, which would clearly include the Republican President.

Did the purported land gift violate Section 21(1)(b) of the Anti-Corruption Act?

For the purposes of examining whether the purported presidential land gift violates Section 21(1)(b) of the Anti-Corruption Act, we can first of all summarise the position by stating that the offence of abuse of office under this section occurs:

(a) when a public official uses their official position to obtain property for themselves or another person; or

(b) when a public official uses information obtained as a result of their official functions to obtain “property, an advantage or benefit” for themselves or another person.

This Section has to be read in conjunction with the definition of “casual gift” as set out in Section 3 of the Anti-Corruption Act which stipulates that a gift must be one that is not “in any way connected with the performance of a person’s official duty so as to constitute an offence under Part III”. Part III is of course where Section 21 resides.

What this means is that:

1. Even a casual, modest or unsolicited gift will constitute an offence under Section 21(1)(b) if it is in any way connected with a person’s official duty.

2. A gift given as a gesture of goodwill will constitute and offence under Section 21(1)(b) if it is in any way connected with a person’s official duty.

3. The use of the official position is what creates the offence of ‘abuse of office’ and is what amounts to corruption. Section 21(10(b) does not say the offence occurs when someone “abuses” their official position but when one “uses” their official position meaning you only have to show that the property or benefit was acquired through the use of the official position.

4. To argue that the receipt of the gift has to have been preceded by abuse or evidence that acceptance of the gift was prejudicial to the interests of the nation would defeat the entire purpose of Section 21(1)(b). We can use a simple analogy to amplify this point: if the law was to state that to enter Parliament buildings after 18:00hrs is an offence, it would be strange to argue that for anyone to be found guilty of the offence of entering the building after the stipulated hour, prosecutors would have to show that the offending person entered the building before they had actually entered it.

5. There is no requirement under Section 21(1)(b) to show the receipt of a gift has to be preceded by evidence of abuse. The act of using one’s official position to receive any gift is what constitutes the abuse, not the action before receiving the gift.

6. In summary, accepting a gift that is given as a gesture of goodwill will constitute an offence of abuse of office if that gift is connected to the performance of a person’s official duty, no matter how small. This is clear when you look at the construction of the definition of “casual gift”. The simple question to be answered by the Republican President is this: “Did he or did he not receive the eSwatini land in the course of the performance of his official functions”? The question is not: “Did he abuse his office before accepting the gift”, as your opinion would have us believe.

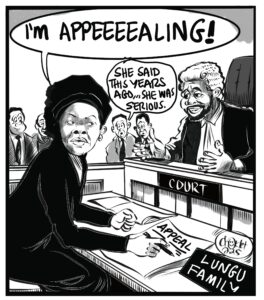

It is possible that this matter will only ultimately be settled by the courts of law but I thought it prudent to set out my summation of the key arguments underlying this important national debate.