The Public Order Act Chapter 113 of the laws of Zambia (henceforth “the Act”) was enacted into law on 19th August 1955, during Zambia’s independence struggle. The Act has been amended more 10 times since 1955 and has been the subject of Constitutional challenges without any meaningful change. Successive governments have used the Act to consolidate power by stifling Citizens rights to assemble and protest peacefully. The Public Order Act has been applied in a manner that offends Articles 20 and Article 21 of the Constitution which guarantee the freedom of expression and the freedom of assembly and association. This begs the question, is the Public Order Act necessary in a democratic society?

Article 20(1) of the Constitution provides that a person shall not except with their own consent, be hindered in the enjoyment of their freedom of expression. Article 20(3) provides for instances when limitations on a person’s freedom of expression may be imposed for purposes of maintaining public safety, public order, public health, and public morality provided the same are reasonably justifiable in a democratic society.

Article 21(1) of the Constitution of Zambia provides for the freedom of assembly and association. It guarantees that without one’s own consent, a person shall not be hindered in the enjoyment of his freedom of assembly and association. The limitations on this provision include anything contained in or done under the authority of any law providing for interests of defence, public safety, public order, public health, or public morality, or what is reasonably required to protect the rights and freedoms of other persons. Laws providing for such limitations have to meet the standard of being reasonably justifiable in a democratic society.

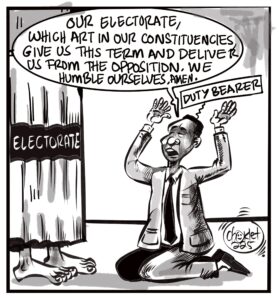

The promotion and protection of democracy and the rights and freedoms of all persons are at the root of our Constitution. Article 91(3) (c), (e) and (f) of the Constitution also provides that the exercise of executive authority by the President shall be to promote democracy, protect and promote the rights and freedoms of a person and uphold the rule of law. Further, Article 8(c) enshrines our national values and principles which include democracy and constitutionalism; these values apply to the enactment and interpretation of the law. Section 5(4) of Act requires every person who intends to assemble or convene a public meeting, procession, or demonstration to give the Police at least 7 days’ notice of that person’s intention to assemble or convene such a meeting, procession, or demonstration. Section 5(4) of the Act provides a list of conditions that may be imposed for purposes of such a meeting, procession, or demonstration. The conditions include the date, time and place, the maximum duration, persons who may or may not speak at the meeting and matters which may not be discussed at such meeting. The list of conditions which may be imposed is long and wide covering, one may argue that these are intended to suppress and dictate the manner in which individuals may express themselves or who they may want to assemble and associate with.

The offences created by sections 6 and 7 of the Act give wide powers to the Police to arrest without warrant any person who violates conditions of a permit imposed under Section 5(4), or the directions given by any regulating officer under section 5(3) of the Act. There is no room for consultation between organisers of a meeting and the police, the police can decide to stop the meeting, procession, or demonstration even after the “permit” is given without accountability to the organisers. Such discretionary and wide powers suppress the full enjoyment of these protected freedoms.

The African Guidelines on Freedom of Association and Assembly of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights adopted at the Commission’s 60th Ordinary Session in 2017, provide member States with guidelines on legislation governing the freedom of assembly and association. One of the fundamental principles of the guidelines is that sanctions imposed by states in the context of associations and assemblies shall be strictly proportionate to the gravity of the harm in question and applied only as a matter of last resort and to the least extent necessary. The offences under the Public Order Act do not align with this fundamental principle, section 6 and 7 of the Act give the Police discretion to arrest without warrant and in practice they have done so with unnecessary use of force and in a militarised manner.

While the maintenance of public order creates a balance between individual freedoms and the protection of the rights and freedoms of everyone else, the arbitrary implementation of the Public Order Act has proved to us that laws that provide for public order can be problematic if they are not continuously reviewed against current demands for democracy. The Public Order Act in its current state stands against Zambia’s aspirations for democracy and the promotion and protection of rights and freedoms and the rule of law in Zambia.

Chapter One Foundation is a civil society organization that promotes and protects human rights, constitutionalism, the rule of law and social justice in Zambia. Please follow us on Facebook under the page ‘Chapter One Foundation’ and on Twitter and Instagram @CofZambia. You may also email us at infodesk@cof.org.zm