Every so often in Zambia, you will hear of someone selling “sugar-free biscuits” or “diabetic-friendly cakes.” You may also find small shops or home bakers advertising these products. Because such foods are scarce here, people rush to buy them. If you live with diabetes, the promise of a safe biscuit or special flour feels like a small miracle. The problem is these labels are not always what they seem. Words like “sugar-free,” “gluten-free,” or “diabetic-friendly” sound reassuring, but unless we unpack what is inside, they can be dangerously misleading.

Let us start with the basics of how food affects blood sugar. Carbohydrates are the body’s main source of glucose, the simple sugar that fuels our cells. In Zambia, staples like nshima from maize meal, millet, cassava, sweet potatoes, bread, rice, chapati, and beans all contain carbohydrates. Once eaten, starches break down into glucose, which enters the bloodstream and raises blood sugar levels. Fibre slows the process, but the glucose still arrives. Protein from kapenta, chicken, beef, beans, and eggs has only a small effect. Fat, whether from cooking oil, groundnuts, butter, or cheese, does not turn into sugar at all, although it slows digestion and can reduce the glucose spike when eaten with carbohydrates. This is why a so-called “sugar-free cake” that still contains flour and starch will still push blood sugar up. The sugar has been removed, but the carbohydrates remain.

Now to the labels. Abroad, “sugar-free” means the product contains less than 0.5 grams of sugar per serving, including natural and added sugars. It is a threshold, not a guarantee of zero sugar. “No added sugar” sounds even more attractive, but it only means no extra sugar was poured in. The product can still contain natural sugars from fruit juice, milk powder, or other ingredients. Most people never check labels down to half a gram, and in Zambia, few products even provide that detail. Sellers take advantage of this. They know that if they write “sugar-free” on a packet, the product looks safe, even when it is not.

The term “diabetic-friendly” is even less reliable because it is not a regulated term anywhere. It is a marketing phrase. At best, it should mean that the food is low in total carbohydrates, high in fibre, and has a gentler impact on blood sugar. A baker might replace white sugar with honey and then declare the cake “diabetic.” These still raise blood sugar. A shop might import chocolates made with maltitol or sorbitol and sell them as diabetic sweets. Those sugar alcohols may raise blood sugar less than normal sugar, but they are not harmless, and in large amounts, they can cause stomach problems.

This lack of clarity matters. Imagine a man in Lusaka with type 2 diabetes who finds “diabetic biscuits” for the first time. He eats freely, trusting the label. Hours later, his blood sugar is dangerously high. The problem is not his discipline. The problem is that the product was poorly labelled, and no one explained that “diabetic” did not mean “carbohydrate-free.” Stories like this create confusion and can put lives at risk. They also erode trust. When people discover that supposedly safe foods still raise their sugar, they begin to doubt all health labels.

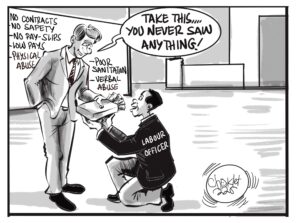

So where does responsibility lie? First with the sellers. If you want to advertise “sugar-free” or “diabetic-friendly” foods, do your research. Do not simply remove white sugar and replace it with honey. That is not the same thing. Do not mix millet flour with cassava and assume the product has no impact on blood sugar. If you do not know, consult a nutritionist. Be transparent. Give clear ingredient lists. Share carbohydrate counts where possible. At the very least, avoid calling your food “diabetic” if you have not tested how it affects blood sugar. Misleading claims may sell quickly, but they endanger the very people you want to serve.

Consumers also need to take responsibility. Do not be dazzled by labels alone. Ask sharper questions. How many carbohydrates are in each serving? How much fibre? What sweeteners are used? In Zambia, we often buy food in markets without nutrition labels, but when someone claims a food is “sugar-free” or “diabetic-friendly,” they are making a health promise. Hold them to account. If the seller cannot answer, think twice before trusting the label. Remember that no matter what the packet says, nshima is still starch, bread is still starch, and flour-based cakes are still starch. The sugar may be gone, but the carbohydrates remain.

Abroad, there are at least thresholds and definitions, but Zambia does not yet have strong regulation on such labels. That leaves people with diabetes unprotected. It also leaves families confused. Regulators should step in, but until then, education is our strongest protection. The more people understand how food is broken down in the body, the better their control over blood sugar. This is why self-monitoring is so important. Check your blood sugar before and after trying these foods. Notice how your body responds. Labels have their place, but your own meter and your own awareness are the best defence. That knowledge is the most empowering label of all.

Did You Know?

One medium sweet potato contains roughly 27g of carbohydrate—that is the same as almost seven teaspoons of sugar once broken down in the body. The form may look different, but the effect on blood sugar is still significant.

Next time you come across a product advertised as “sugar-free” or “diabetic-friendly,” do two things:

Ask the seller how many carbohydrates are in one serving.

If you live with diabetes, check your blood sugar three hours after eating it. Let your body tell you the truth behind the label.

Kaajal Vaghela is a wellness entrepreneur, sportswear designer, and diabetes health consultant with over three decades of lived experience managing Type 1 diabetes. Having previously served as Chairperson of the Lusaka branch of the Diabetes Association of Zambia, she remains a passionate advocate for breaking down myths and building awareness about diabetes. For more personalised coaching or corporate wellness workshops, visit: www.kaajalvaghela.com

and for any feedback: [email protected]