GOVERNMENT is likely to end up refinancing Zambia’s huge public debt because of the possibility of failing to service repayments when they fall due, says economist Professor Oliver Saasa.

And Prof Saasa observed that the country’s current debt figures, coupled with the climatic conditions, clearly prove that the Treasury is strained.

Speaking on Diamond TV’s COSTA, Sunday, Prof Saasa observed that Zambia’s huge public debt stock figures indicated that it was no longer sustainable.

Zambia’s external debt leaped to US $11.20 billion as at December 31, 2019, for the first time in the country’s history, mainly on account of new disbursements on existing loans, mostly earmarked for infrastructure development.

The country’s new external debt position represents an increase of around US $1 billion from the previous US $10.23 billion by June 30, 2019, compared to US $10.05 billion as at December 31, 2018, and US $8.74 billion by the end of 2017.

Data also reveals that Zambia’s domestic debt stock equally jumped to K80.2 billion at the end of last year from K60.3 billion at end-June 2019, compared to over K58 billion by the end of 2018, and K48.4 billion by end of 2017.

“If you look at service of the debt, we have started eating to the social sector expenditure by getting from health and education. Last year, we did that in order to service the debt so that we do not default because defaulting leads you to a debt crisis, which we are not yet there, but if you fail to manage it properly, you may run into a serious problem. Firstly, our debt is not sustainable at the moment; government has said so; the IMF said so two years ago when they said you have actually toned down. The figures show you that we may not actually be able to deliver the debt; we may end up refinancing,” Prof Saasa said.

“What it means, then, is two-fold: firstly, tone down on your contraction of new debt. Now, US $11.2 billion, so, meaning during this period, we have actually acquired close to a billion (dollars); it means there is something that is happening where we are failing to restrain our appetite; that is what exactly it means. When the first Eurobond of US $750 million, the bullet payment is due in 2022, and the Sinking Fund at the moment, of course, there is likely any money; so it means we have to refinance. Refinancing means that we have to sell the setbacks to someone, but we are going to pay more!”

He said government needed to reduce on its expenditure pattern and focus more on income-generating programmes.

“The message from the Minister of Finance (Dr Bwalya Ng’andu), and I like it, what he is saying is that, ‘let us reduce our expenditure pattern!’ The generators of excess expenditures are Ministries. Take, for example, Ministry of Health; we all want hospitals. What is a hospital? A hospital is not just a building, a hospital is a combination of a number of factors apart from the buildings, you are talking about the doctors; you are talking about medicines; you are talking about diagnosis equipment; you are talking about support staff and healthcare givers, including nurses and paramedics…all those become a hospital. So, each time you build a new hospital, much that it is required, you have to look at your resource envelop because immediately it becomes a recurrent cost centre,” he said.

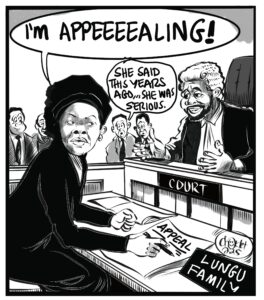

“If you build 10 hospitals, it is good, politically, and, of course, it is appealing to the people. But the question is: would you be able to maintain those? When you go to the hospital and you discover there are no drugs, don’t get surprised because you have actually run much faster in the facilitation of the building without the doctors, without the medicines, without everything. So, now, the Minister of Finance will have to be dumb-founded because the question will be: where do we get the money to run these hospitals that we have created?”

And he observed that the country’s current debt figures, coupled with the climatic conditions, clearly proved that the Treasury was strained.

“Figures tell you something. If you look at the debt servicing and you combined it with the civil service salaries, they account for slightly above 90 per cent of government revenue. So, when you talk about the effects of climate change, flooding and the like, it means there is significant stress on the Treasury and this is not the time one can be envious of being a Minister of Finance; it is a challenge that has to be contended with! The challenges that associated with climate change can be easily programmed in a certain degree; they must be anticipated. Almost every two to three years we will have a climate like this; it is almost standard in the past 20, 30 years. You will have to prepare for it; you have to budget for it, of course, when the economy is not performing well; you will have a challenge. But if each time it comes you call it a disaster, it means you are not prepared. At the end of the day, if you are not prepared for something that is anticipated, it is no longer a disaster, you are the disaster!” argued Prof Saasa.

“Import cover essentially means that if a disaster was to happen today, and looking at our expenditure pattern, we have to import things to balance things to make them level. We can only survive for six weeks. If a disaster happens, the room for manoeuvre by the Central Bank or generally the Executive is restrained. That is where the challenge is; when you put that together with debt stress, which is also bringing up some challenges. That is why when you bring in the IMF (International Monetary Fund), they will tell you that one of the challenges and major drivers to the level of your own expectations and the projection that you put is that you have to tame your appetite for contracting sovereign debt. You are actually bearing much more than you are not able to service. You heard the honourable Minister last week; he was actually appealing to government: ‘let’s narrow down our appetite for contracting more debt in certain sectors some of which may include infrastructure’.”