About nine months ago, on 29 September 2017, six human rights defenders and activists staged a peaceful protest outside the Parliament buildings in Lusaka to demand answers for the controversial purchase of 42 fire trucks by the government in 2015 at a cost of US$42 million. Zambians questioned both the procurement process and the cost of the trucks. Many expressed outrage with the exorbitant cost and saw this as a misuse of public funds in a country where millions are living in poverty.

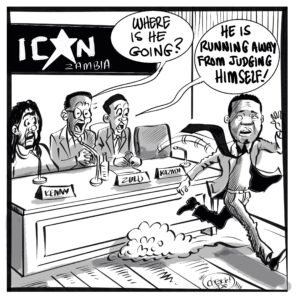

Among the activists on that fateful day in September was a renowned musician and artiste Fumba Chama, also known as Pilato. No sooner had the activists gathered, the police descended upon them, using excessive force. They were beaten, arrested and charged under the Zambian Penal Code with “disobeying lawful orders”. They were later released on bail pending trial. In a sad twist of events, Pilato fled the country early this year after receiving a video message in which supporters of the ruling party threatened to beat him for releasing Koswe Mumpoto (rat in the pot), a major hit song criticizing the ruling elite. When he failed to turn up for the hearing in February, a warrant for his arrest was issued. He returned to the country on 16 May, only to be met at the Kenneth Kaunda International Airport by a contingent of police officers who promptly arrested him. He was later released on bail.

The trial of Pilato and the five other protestors begins today in Lusaka, coincidentally, the same day that the 31st Summit of the African Union kicks off in Nouakchott, Mauritania. A discomforting irony surrounds this coincidence. As the prosecution will be trying to build a case against Pilato and his co-accused, leaders from across the continent will be reflecting on and discussing this year’s African Union (AU) theme: ‘Winning the fight against Corruption: A sustainable path to Africa’s transformation’. Given these recent events at home, what contribution the Zambian delegation will make during this discussion is a matter of pure conjecture. What is clear is that domestically, Zambia is pursuing the fight not against corruption, but against the very people who are calling for transparency and accountability in the use and management of public funds; the very people the authorities should encourage and allow to participate in the fight against corruption if the authorities are ever going to successfully combat corruption.

By all accounts, the trial that begins today is a cynical attempt to suppress the voices and belittle the actions of those who are leading the fight against corruption in Zambia. The questions around the procurement of the 42 trucks reflect concerns about a deeper or endemic corruption problem in the country. In 2017, the Zambian Financial Intelligence Centre reported that an estimated US$450 million was lost through tax evasion, corruption, money laundering, and fraud. Corruption amounted to a massive 39% of the number of reports analysed, with many cases linked to procurement contracts involving government and quasi-government institutions.

The trial of Pilato and the five other protestors is also a reflection of yet another bigger concern: the shrinking or dwindling space for the rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association in Zambia. In the recent past, there have been many shameful attempts to silence critical voices. Individuals who criticise the government have been anonymously contacted and threatened. Peaceful assemblies have been interrupted and broken up by the police, often time with the use of excessive force. The cumulative effect of these unfortunate actions is to prevent the people from holding their government to account.

As Zambia participates in the discussions on this year’s theme of the AU, it must reflect on its commitment to the continent-wide resolve to prevent and combat corruption. Is the government strengthening or undermining this resolve? Is it even genuinely part of this resolve in the first instance? An honest answer to these questions should prompt the government to recall its voluntary obligations under the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption, which Zambia ratified in March 2007. Under this Convention, Zambia has undertaken to abide by a specific set of principles, including “respect for human and peoples’ rights in accordance with the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and other relevant human rights instruments” and “transparency and accountability in the management of public affairs”. The combined effect of these commitments is that the government must change course. It must respect the rights of those who speak out against corruption. It must guarantee, promote and respect their rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association. And in the immediate term, crucially, it must unconditionally drop all charges against Pilato and the five other protestors.

Only when Zambia starts to live out the principles espoused by the African Union in the fight against corruption, will it truly be able to play a meaningful role in the continental efforts to end the problem.

The Author is Africa Director for Research and Advocacy at Amnesty International