Is there such as thing like ‘let us cut a million-tree campaign in Zambia? Yes, there is but only in practice. This submission dares to make an argument that what Zambia is currently experiencing is somewhat of a campaign aimed at cutting only a million trees – environmental destruction and deforestation to the core. I extend this to suggest that without a national system of national innovation, it will be very difficult to win any arguments around climate change and environmental protection in the country. Some of this relate to fluctuations between sounding climate and environmental protection alarm bells on the one hand to ignoring them on the other – all within one country context. Here, I show how problematic this is for the wider arguments on climate change and environmental protection.

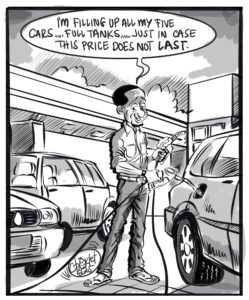

The World Bank recently reported that clearing forests for agriculture, charcoal and fuelwood production, are among the country’s main drivers of deforestation. Zambia’s deforestation rate is remarkably alarming – 5th globally with an average loss of between 250,000 and 300,000 hectares of forest every year. In early 2017, President Edgar Lungu reported the country was losing an average 276,021 hectares of forest per year between 2000 and 2014 thanks to deforestation. By implication the country lost 3,864,294 hectares of forest in just over a decade and it can only get worse. With the unprecedented energy crisis, things can only get worse especially that the existing power utility company is a shell of its former self – reducing itself to formulating load shedding timetables (which it hardly follows) as opposed to showcasing innovation for energy diversification. Rather than showcasing cutting edge innovations with great profitability potential, ZESCO has since asked the public to reduce consumption of electricity and most importantly consider other sources. Indeed, high poverty levels in Zambia (85% of the population living on less than US$2 per day) means that many people see a unique profitability potential in the energy crisis to enhance charcoal-based livelihoods. Charcoal has witnessed a sharp demand growth as a cheap source of energy for household cooking needs in Lusaka and other cities. Indeed, in some areas in Lusaka, charcoal prices have moved from ZMK50 to ZMK120 per 50kg bag, leading to steep rates of illegal and destructive tree cutting.

As if that is not enough, inefficient subsistence agriculture expansion among farmers is reportedly destructing deforested areas. Our recent research has shown the downside of road infrastructure expansion across rural areas. The argument is that distant, inaccessible and less appealing rural geographies now connected through road infrastructure have now become desirable and up for grabs, enhancing land use expansion across various uses including agriculture. Within agriculture, land use expansion have been recorded in crops such as soya beans – warranting a soy transition. Recent reports such as by Dr Felix Kalaba of the Copperbelt University show that agricultural production increases deforestation in two ways. Firstly, farmers may engage in charcoal production to raise income to purchase agricultural inputs, and secondly land under cultivation may be increased to increase crop yields. Several research projects including our own there is a lack of intersectoral cooperation and coordination between the agriculture, energy and forestry sectors, indicating a need for a more holistic landscape management approach to bridge sectoral divides.

All these play out in the wider culture of politics. Many speeches and alarm bells such as those coming from Edgar Lungu’s State of the National Address (SONA) appear in isolation. Efforts around environmental protection are guarded in silos. Our research has shown tensions and contestations between and among state departments, raising challenges for coordination of environmental efforts. Institutions responsible for the management of the environment appear in isolation with little room to manoeuvre such as on controversial large-scale projects. Rather than making recommendations, these institutions have failed to get their maximum weight on protecting their recommendations. This is not a question of capacity only. It is my opinion this is also the question of the nature of politics at play which entrenches unsustainable environmental practices. The case of the lower Zambezi and Forest 47 strengthens this point.

This brings me to the country’s obsession with mining, an account which raise issues at the heart of contested development debates in Zambia and southern Africa. A resource-led agenda has been at the heart of Africa’s development strategies. The argument is that allowing capital – often foreign capital – to exploit our natural resources can lead to sizeable benefits for the host country. This argument points to opportunities for revenue collection for the state, employment creation and generation of foreign exchange. But this view is false and completing misleading and it appears our politicians will never repent from the injustice imposed on Zambians through the erstwhile privatisation of the mines. Mining companies are not interested in Africa’s development, and are not interested in supporting policies that will transform the continent’s development. Despite the rhetoric, they have violated human rights and left communities dispossessed. Zambia is replete with historical cases of such violations.

The history of mining in Zambia shows that international mining companies will continue to extract high profits from the continent whilst peddling a false view of corporate social responsibility. Ray Bush and Yao Graham, writing for the Guardian argue that “[w]ith the support of their home governments, including the UK, they have pressured African governments to introduce policies that have resulted in dispossession of communities, environmental degradation and human rights violations, while yielding woeful revenues for national treasuries. They continue to argue that this asymmetry of power, between mining companies on the one hand and African states and communities on the other, is one of the many issues obscured by the heavy focus on aid and governance in the debates about Africa. So, what does Zambia want to achieve in the lower Zambia that has not been achieved in Kabwe, Munali, Copperbelt and North-Western provinces? What does this mean for the agenda on climate change as advanced by the President’s SONA and environmental protection as highlighted in different policy documents?

I go back to the beginning that practices in agriculture, water resources, energy in Zambia can only point to one thing: that Zambia might be on a campaign of let us cut only a million tree. I extended this to suggest that without a national system of national innovation, it will be very difficult to win any arguments around climate change and environmental protection in Zambia. Some of this relate to fluctuations between sounding climate and environmental protection alarm bells on the one hand to ignoring them on the other – all within one country context. I show how problematic this is for the wider arguments on climate change and environmental protection across various sectors. We can borrow from the Cree Indian Prophesy when the last tree is cut, the last fish is caught, and the last river is polluted; when to breathe the air is sickening, you will realize, too late, that wealth is not in bank accounts and that you can’t eat money. Once again, this transitory moment in the history of development of our country deserves to be understood – at least by all well-meaning Zambians.

(Simon Manda, PhD (Lecturer, University of Zambia). His research interest in Environmental Sustainability and Rural Livelihoods Comment: [email protected]. ‘When it’s a matter of opinion, make your opinion Matter’)