Throughout the year 2021, Zambia experienced no shortage of disappointments and set backs in the political landscape. Yet there are some individuals and institutions whose actions, courage and principles offered hope and inspiration in a year that was dominated by a historic vote that saw the defeat of incumbent president Edgar Lungu and the election of long-time opposition leader Hakainde Hichilema. In this article, I focus on the conduct of those in public political life who risked the ire of the authorities in defence of the common good, or whose actions, some reported in the mainstream media, contributed to the consolidation of democracy.

Edgar Lungu

After many years of sliding into authoritarianism and acute economic decline, Zambia reclaimed its democracy and set itself on a possible path to economic recovery with the election of Hichilema in August 2021. Ironically, one person who deserves much credit for this change in direction is former president Edgar Lungu. So calamitous was his leadership that he inadvertently united most Zambians to register as voters and oust him via the ballot. Ordinarily, it takes many people and institutions to raise the collective civic consciousness of a population. Thanks to his incompetence, Lungu achieved this task almost single-handedly.

Then, despite all his anti-democratic machinations before the vote, after losing it, he gracefully conceded (though not before negotiating terms with his would-be successor), congratulated the president-elect, and presided over a smooth transition. It is worth noting that Lungu could have challenged Hichilema’s election in the Constitutional Court, an option that is available to any losing presidential candidate. Had he done so, it is not inconceivable that the court, which was widely seen as biased in his favour, would have invented reason to nullify the election of Hichilema. Such a decision may have triggered violent protests and plunged the country into turmoil. Democracy usually thrives on unwritten norms. In many cases, these turn out to be more important than the written rules. Although Lungu’s concession was strictly not necessary, it was crucial to paving the way for a smooth transition and consolidating Zambia’s culture of peaceful transfers of power whenever an incumbent is defeated.

Hakainde Hichilema

Hakainde Hichilema has stood in successive elections since 2006, but it was as if everything he did in the past was preparing him for 2021. At a critical moment, he emerged to carry the aspirations of a generation, serve as a symbol of what is possible, and inspire the hopes of so many millions of Zambians who, overwhelmed with a collective sense of hopelessness, were on the brink. These included the ordinary citizen weighed down by the high cost of living, the common man and woman eking out a living from the street, the impoverished parent who could no longer afford to send their child to school, the student whose living allowance was withdrawn at short notice by the Lungu administration, the restless graduate looking for a formal job, and the withered retiree whose benefits remained unpaid years after serving Zambia so diligently.

Others were the dismissed, dispirited or highly indebted public sector workers including the poorly paid teacher and health worker, the marginalised citizen in rural communities, the urbanite who longed for a return to law and order, the soldier living in deplorable conditions and barracks unrenovated since Kenneth Kaunda’s day, the professional police officer fed up of receiving instructions from the political elites in power, the small-scale entrepreneur whose concerns went unnoticed, the hardworking farmer whose yield went to waste or fetched a price that hardly met the cost of production, and the mineworker who sought a win-win solution to the challenges at Mopani and Konkola Copper Mines.

All these diverse interests and dreams were placed into the custody of Hichilema, an enormous load for one person to bear and which I suspect keeps him awake at night. Will he disappoint or will he deliver? Time will tell. Neighbouring countries scheduled to host elections over the course of the next few years, such as Zimbabwe in 2023, will likely look to Zambia for evidence of the effects of political change. The first few months of the new presidency have shown a combination of promising steps to progress and some highly alarming signs of broken promises.

The Zambia Army

The professionalism of the leadership and rank and file of the Zambia army is a decisive reason why the country had a peaceful election and transition. Nearly two weeks before the election, Lungu deployed the military onto the streets of the 10 provinces in the name of preventing potential violence. If the objective was to promote the partisan political interests of the incumbent and his Patriotic Front (PF) party, then it spectacularly failed. When police officers tried to curtail the free movement of Lungu’s main rival during eleventh hour campaigns in Kapiri Mposhi and Nakonde, for instance, and requested for a helping hand, the deployed soldiers refused to cooperate in the scheme. Then, when it became apparent that he was losing the election, the then president attempted to influence the outcome with a two-fold strategy.

First, he tried to exert pressure on the Electoral Commission of Zambia (ECZ) to cancel the election results for violence and alleged irregularities in three provinces that had historically voted for the opposition. Lungu cited the unexplained killing of a PF official in Northwestern province and unsubstantiated claims that agents of the ruling party had been chased from several polling stations in Southern and Western provinces as evidence of an unfree and unfair election. The ECZ asserted its independence and refused to co-operate. Second, the outgoing president then reportedly turned to the military for support, according to well-placed sources in the security and intelligence services. Unfortunately for Lungu, the soldiers, who overwhelmingly voted against the incumbent in nearly all the barracks, refused to intervene. The latter point possibly explains the incumbent’s willingness to hand over power, but only after he had successfully negotiated the terms of his exit with his soon-to-be successor, which saw him dropping his plan to challenge the election results in the Constitutional Court in exchange for the non-removal of his immunity after stepping down. The role of soldiers in Zambia’s transition, especially when seen in the context of the previous refusal by elements of the army to back the attempts of former president Frederick Chiluba to secure an unconstitutional third term in 2001, demonstrates how the military remains an important political actor in Africa for better or for worse – and that it may in some cases be more likely to secure rather than undermine democratic gains.

UK High Commissioner to Zambia Nicholas Woolley and US Charge d’affaires to Zambia David Young

Diplomats are international citizens. They are the eyes and ears of the world in the country that hosts them. Their job is to shine light on what is happening in that country. If they keep quiet, the world will think everything is fine. Notwithstanding their diplomatic postings and their need to respect local politics, diplomats have a responsibility to maintain an international order that respects democracy and human rights. In the run-up to the August general election, President Lungu’s administration became so repressive that it struck fear even among several diplomats accredited to Zambia who kept a disturbing silence amidst murderous attacks on democracy and human rights. Those who dared to criticise or cross paths with the authorities were declared persona non grata and promptly expelled. Among the victims were United States Ambassador to Zambia Daniel Foote (expelled in December 2019), South African High Commissioner Sikose Mji (September 2018) and Cuban Ambassador Nelson Pages Vilas (April 2018).

Riding against this climate of fear was UK High Commissioner to Zambia Nicholas Woolley and US Charge d’affaires David Young. As well as holding a series of fruitful meetings with ECZ officials on voter registration and strengthening the capacity of civil society to monitor the elections, Woolley combined shuttle diplomacy with public condemnation of human rights violations and the lack of a level playing field ahead of the election. He was scathing on violations of the right to public assembly, freedom of expression and association and the lack of equal access and coverage on public media by all political contenders. Young went further, delivering a strongly worded public statement on the eve of the elections. In it, he warned that the American government would impose visa restrictions, travel bans and financial sanctions on government officials, quasi-governmental bodies, security and police forces, political party members, business financiers, election managers, or any other individuals who promoted violence, undermined electoral process, engaged in fraudulent or corrupt behaviour, or otherwise violated democratic rights and the foundations of free elections.

Young’s warning may explain why several individuals in key institutions who had appeared compromised ahead of the election ultimately fell into line. By threatening to enforce travel restrictions on the errant officials, the American diplomat tapped into the gullible psyche and inferiority complex of many African political and economic elites whose measure of success in life is linked to their ability to obtain a visa to travel to Western countries. For such figures, cutting that link constitutes a form of amputation or emasculation. The fact that the threat was extended to their family members upped the stakes further. This was not the only occasion when the threat of a travel ban made a critical contribution to Zambia’s democratic process. A few days before the 12 August election, an opposition leader on the presidential ballot hatched a suspicious plan to quit the race, amidst speculation that the governing party, sensing defeat, was attempting to delay the poll to devise ways of excluding Lungu’s main opponent or change its unpopular running mate. According to Zambia’s constitution, the withdrawal would have caused the cancellation of the presidential election, the filing of fresh nominations by eligible candidates, and the holding of a new election within the next 30 days.

Upon learning of the scheme, a senior diplomat met the concerned candidate and threatened to revoke a long-term existing visa that had earlier been issued to them. This intervention was enough to force the individual to immediately abandon the idea, which then paved the way for the vote to take place as scheduled. One or two other diplomats also helped to secure the peaceful election. For instance, when the police twice attempted to arrest Hichilema (first in December 2020 over private farmland he had procured in 2004 and then in April 2021 in connection with two missing, allegedly abducted, people linked to the same case) as part of a wider strategy to exclude him from the 2021 election race, it was a few diplomats who intervened on both occasions to thwart this.

Rupiah Banda

The death of Zambia’s founding president Kenneth Kaunda in June 2021 left the previously polarising Rupiah Banda as the only surviving former president ahead of the August election. Frederick Chiluba, who had defeated Kaunda in 1991 and led the country for a decade, died in June 2010.His successor Levy Mwanawasa died in office in August 2008 and was replaced by Banda, hitherto Mwanawasa’s vice-president, who won the subsequent presidential by-election. In the scheduled general election of September 2011, Banda and his then governing Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD) were in turn defeated by the PF under Michael Sata. Following Sata’s death in office in October 2014, Banda, who still commanded significant national support within the MMD, staged a political comeback. He attempted to oust Nevers Mumba, who had succeeded him at party level, from the leadership of the MMD and install himself as its candidate in the presidential by-election. When the Supreme Court ruled that Mumba was the MMD’s rightful nominee, Banda, who hails from the same language group and province as Edgar Lungu, the PF candidate in the election, abandoned his party and urged his supporters to vote for Lungu, whom he successfully campaigned for in both the 2015 poll and the 2016 general election.

Before and after the August election, Banda did three things that elevated his status and contributed to a successful transition. First, following Kaunda’s death, he finally embraced the role of a statesman, stressing the importance of national unity, having a peaceful election, and adhering to the five golden rules of preventing the spread of Covid-19. Second, he decided against endorsing any presidential candidate, a move that was generally interpreted as a vote of no-confidence in Lungu and a message to his supporters to vote for other candidates. Amidst growing fears that the incumbent, fearing possible prosecution if he lost the election, may not concede defeat, Banda issued a strongly worded public statement in which he urged all the candidates to respect the will of the people: “Any attempt by any entity acting alone or in consent with others to impose the leadership outside the concept of one man one vote would be an assault of sacrifices of our founding fathers and will imperil the sovereignty and independence of the country and also jeopardise peace and unity of this generation and those to come,” he said, before pleading “with [the would-be] winners to remain humble, magnanimous, and show respect to losers. On the other hand, the [would-be] losers must be able to accept the defeat, congratulate the winners, reorganise themselves, and try again in the next elections.”

Third, following the election, Banda played a crucial role in getting the incumbent to concede amidst rising tension in the country. He organised the closed-door meeting that brought together the outgoing president and president-elect Hichilema, who was reportedly furious that he was not being allowed to win the election. The meeting was also attended by Ernest Bai Koroma, the former President of Sierra Leone who headed the African Union Election Observation Mission, and Jakaya Kikwete, the former President of Tanzania who led the Commonwealth Observer Group. Shortly after the meeting, Lungu who had initially planned to challenge the results in the Constitutional Court, switched tack. In a short, televised address, he conceded and congratulated his soon-to-be successor, who in turn addressed him, saying “do not worry; you will be okay, sir” – remarks that were widely seen as the public expression of the two men’s private political settlement; namely, that Lungu would drop his planned legal challenge in exchange for not lifting his immunity after stepping down.

Banda’s intervention ended the heightened political tension and averted possible chaos. There is also a wider point to be made here about the possible institutionalisation of the role of former presidents in political transitions in Africa. The Zambian experience shows that incumbents are more likely to concede defeat and preside over a peaceful transfer of power when they are encouraged to do so by those with that experience. When Banda lost the 2011 election, reports suggested that he was persuaded to concede by Kaunda who, having done the same in 1991, provided the clearest example that it is possible to retire and be a respected former president. Zambia has thus created the norm where power is somewhat divided between an incumbent and a previous president and where the former president will step in at a crucial moment and moderate the latest leader. In other words, what we are seeing in Lusaka is a process of transition in which come the next election, it might be Lungu who would be called upon to broker the next transition, which gives former presidents a hugely significant role.

The voters, especially young people

Democracies survive on the strength of formal institutions and mass support for democratic processes and outcomes. Since 1999, survey data by the Afrobarometer has consistently shown that a majority of Zambians think democracy is the best political system for the country, even during the preceding seven years of authoritarian drift. In keeping up with this trend, the country’s citizens carried out four important pro-democracy tasks in 2021. First, with less than a year before the election, the electoral commission moved to abolish the existing voters’ roll, numbering 6million, and draw up an entirely new one in a 30-day window. If the objective was voter suppression, then it failed as 7 million people in both rural and urban areas defied long distances, heavy rains, and the shadow of an invisible threat in Covid-19 to register as voters.

Second, of those who registered, 70 percent voted, the highest turnout since the 2006 election. Most of these were young people who were first-time voters. Of the 4.8 million who cast valid votes, 2.8 million or 59% chose Hichilema, while 1.8 million (39%) supported Lungu. The remaining 2% voted for the other 14 candidates. Third, after voting, Zambians kept vigil at polling stations to guard or protect the vote. Their alertness and vigilance made it difficult to manipulate the results. Finally, following inauguration, they refused to go to sleep, choosing instead to hold the new government to account by finding their voice during the remainder of the year on the choice of presidential appointments to public office and governance issues more generally. By actively participating in the democratic process, Zambians stood up for the issues that they care about, decided who should lead the country for the next five years and made their voice heard. In the end, the real winner was Zambia’s democracy.

John Sangwa

One of Zambia’s most admired and honourable lawyers, John Sangwa has become more of an institution. So credible is his voice on issues of good governance and constitutionalism that it strikes fear in elected leaders who betray public trust, has become the go-to source for ordinary Zambians seeking to understand complex ideas, and commands great attention even in silence. Last year, he placed his head above the parapet to hold the authorities to account in three main ways.

First, Sangwa initiated or handled several court cases against the abuse of state power and breaches of Zambia’s constitution by the Lungu administration. Though he hardly won any, the cases demonstrated the compromised state of the judiciary and drew attention to the erosion of the rule of law. Second, Sangwa contributed towards a growing culture of legal activism through informed media commentaries on relevant issues of public interest. As most Zambians retreated into silence for fear of repression, he railed against the incompetence of Lungu, the high levels of political intolerance and corruption in government, the debilitating public debt, and the extreme levels of poverty and inequality. His persistent attacks raised awareness among voters, helped delegitimise the governing party, and contributed to Lungu’s defeat. Third, after the transfer of power, Sangwa showed consistency by turning his attention to the governance slippages of the new presidency. In addition to criticising Hichilema’s failure to initiate a transparent process of choosing judges before the presidential appointment of the new Chief Justice, he lambasted Lungu’s successor for backtracking on key campaign promises. For instance, when campaigning in opposition, Hichilema promised to reduce the cost of petroleum products for consumers, claiming that rampant corruption by PF officials and unnecessary middlemen were responsible for the high prices. Immediately after his election, he increased the fuel price by 33 percent and resisted public calls to explain the U-turn, which undermines public trust.

Sangwa’s heroic activism has earned him the respect and admiration of Zambians who appreciate his contribution to protecting the rule of law and defending democracy and the constitution. Predictably however, it has also led to huge risks to his personal security, some of which can be blamed on the new government. So sensitive to public criticism and afraid of his towering voice are senior members of the Hichilema presidency that they have already started harassing Sangwa’s closest relations as part of a calculated strategy to intimidate him. Given the absence of a credible and effective political opposition and the fact that many of the critical voices from academia, civil society and the church who spoke truth to power under Lungu have failed to remain impartial after Hichilema’s election, individuals like Sangwa will assume ever greater significance in 2022 and the years to come. The demobilisation of progressive forces has seen previously neutral voices become part of the choir of praise or lulled into silence after the opposition they supported won. Others have been co-opted into government through appointments to parastatal boards or presidential advisory entities, while one or two have applied for professional ranks that can only be conferred by the president and are therefore unlikely to speak out on Hichilema’s worrying tendencies unless their bids fail. Most remain in the long queue for appointments to public office.

Unless this context changes or new progressive voices emerge, Zambia’s democracy may suffer from the absence of a robust non-state sector capable of checking the power of the government. Already, there are serious questions about Hichilema’s commitment to fighting corruption, but civic bodies that could have previously raised alarm have taken a back seat. Elected on a platform of anti-corruption, accountability and transparency, Hichilema has so far failed, in Trumpian fashion, to release his assets value –the first major-party presidential nominee and Zambian president, alongside Lungu, in more than 30 years not to disclose his net worth. Zambian presidents have generally used state power to accumulate. For instance, in less than sixteen months in power, Lungu’s net worth grew from K10.9 million when he first ran for election in 2015 to K23.7 million in 2016 when he ran for re-election. Since the president’s salary is gazetted and he had no known businesses, angry Zambians demanded to know the source of this exponential growth of his earnings. Lungu’s failure to explain fuelled accusations that he had acquired the wealth corruptly. The former president’s assets value may have increased considerably since 2016, which could explain why he did not release his net worth last year out of fear that the public’s knowledge of his opulence would increase calls for the removal of his immunity if he lost the election. Although there is no evidence to suggest that Hichilema has started stealing public funds or using public office to promote his private interests, the president’s reluctance to publish his net worth is most concerning, given his extensive business interests. Zambians interested in knowing the difference in his assets value between 2021 when he assumed office and, say, 2026, when he will be filing his nomination papers for a second term, will be left frustrated.

Telesphore Mpundu

Every country deserves its Desmond Tutu – the conscience of the nation. For Zambia, the person who comes close to that standing is retired Catholic Archbishop of Lusaka Diocese Telesphore Mpundu. The 74-year-old is a dignified individual who exercises his constitutional rights and is among a very small number of the Zambian clergy who are incapable of finding peace in an environment in which human suffering is manufactured by politicians. Throughout last year, Mpundu, as he has consistently done for much of his public life, raised both his voice and the quality of his argument to speak out against human rights violations, corruption in government, the shrinking democratic space, the indifference of the country’s political leadership to the plight of many, and the constant harassment of Hichilema. It is as if he was spurred by the knowledge that to be silent in the face of these human-made sins is to actively participate in sustaining the status quo.

In addition to bearing sympathy for the elites in power who found his ability to speak out on issues of public interest unbearable, the man of God refused to be bullied into silence by the governing party’s familiar tactic of accusing anyone who criticised Lungu’s administration, however well intentioned, of being an opposition supporter. A highly principled individual with the strength of convictions respected even by his adversaries, Mpundu served as an inspiring example of the kind of clergy Zambia and indeed Africa needs – those with a deep sense of responsibility and a conscience that is restless in the face of injustice, human rights violations and the degrading poverty that surrounds them.

Justice Margaret Munalula

Many Zambians generally consider the Constitutional Court as the slaughterhouse of the country’s justice system because of its often reason-averse judgments, lack of demonstrable commitment to protecting the Constitution and the rule of law, and failure to render decisions in a timely manner. Despite being a nascent court, it has done more damage to Zambia’s democracy than the conventional courts that safeguarded constitutional order before its founding in 2016. The only person on the nine-member court who has consistently tried to stay true to its constitutional mandate even in the face of executive pressure, outright intimidation, and obstruction from the ruling elites, is Mulela Margaret Munalula. When eight of her colleagues went out of the law in June 2021 to rule that Lungu was eligible to stand for another term of office because the eighteen months he had served as president following Sata’s death constituted an ‘inherited term of office’ – a proposition that is not supported by the constitution and overlooks the fact that he was ushered into office through a competitive presidential by-election – Munalula dissented. Seeing the matter concerning Lungu’s eligibility to stand for a third term as a landmark case which offered the country a chance to develop its constitutional jurisprudence, strengthen its democratic credentials and restore public confidence in the Judiciary, Justice Munalula delivered a convincing minority judgement showing that Lungu had twice been elected, twice been sworn into office, and was constitutionally barred from standing for a third term.

In taking this position, she confirmed her growing public reputation as the court’s most independent-minded judge, who prefers to give a progressive interpretation of constitutional provisions at the risk of being seen as anti-executive. Zambia’s judiciary will be better off with justices like her – those with the qualities she possesses, which are admired and treasured by her colleagues: an active conscience, a keen mind, intelligence, fairness, devotion to scholarship, and a willingness to learn, to understand better, to judge better. Munalula’s consistent utilisation of these outstanding attributes in a way that lives up to fulfilling the mandate of the Constitutional Court – protection of the constitution – is inspiring and gives hope to many. Individuals like her sustain the struggle for an effective and impartial judiciary that is not susceptible to political and financial interests, and which is unafraid of asserting its constitutional power, even if this means ruling against the government and the ruling party.

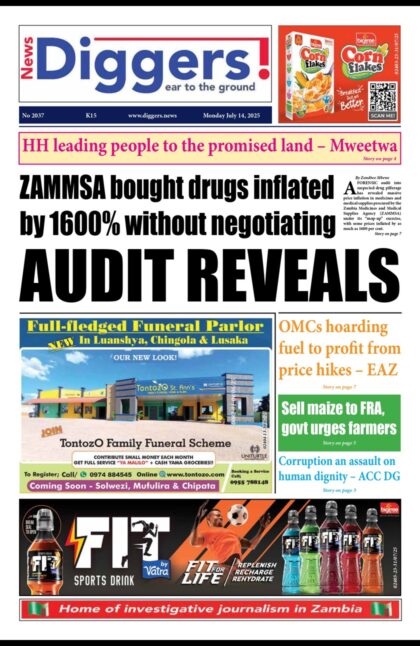

News Diggers newspaper

Established in 2017, News Diggers has emerged to becoming the most influential and trusted newspaper in Zambia. Last year, the publication stood out as a rare bright light in the country’s dysfunctional democratic institutions. As well as holding power to account and providing an important platform for increasing public voices in the processes of governance, the newspaper exposed several scandals in government, kept open the civic space despite operating under a political climate that was hostile to critical free press, provided a platform for major political players to articulate their campaign promises ahead of the election, and published stirring editorial comments whose depth and wisdom were truly inspiring. Like in many African countries, to be a journalist in Zambia is risky, less financially rewarding than other careers, and requires a lot of sacrifice. That is the more reason why the editors and reporters of News Diggers deserve praise for their inspiring passion, dedication, commitment to work and for running the paper so well on a shoestring budget.

Andrew Ejimadu alias Seer 1

The flamboyant Nigerian self-styled prophet Andrew Ejimadu, popularly known as Seer 1, arrived in Zambia around 2010, grew his ministry over the next seven years and became part of the protestant Christian community. As well as rooting himself in the country’s spiritual fabric, he also began to rub shoulders with the powerful political elites in president Lungu’s Cabinet. Somehow, he fell out with the authorities, who deported him in April 2017. By that time, however, he had become a Zambian by faith and learnt three things about many of the people he was leaving behind: their gullibility, hypersensitivity to the occult and Christian fundamentalism. Using South Africa as his base and Facebook as his organising platform, Seer1 held a series of online meetings in which he railed against the then ruling PF. Initially, many saw his antics as motivated by vendetta following his deportation. As such, in the beginning, his live chats provided the much-needed comical relief in what was a highly polarised and depressing pre-election environment. Things changed in 2021 when Seer 1transformed himself into a well-informed analyst of Zambian politics, mixing the ultra-bizarre (claims that the PF would lose because he had withdrawn the black magic that he gave them to win power in 2015 and 2016) and the sensible (sound understanding and analysis of the country’s geopolitics, economic issues and how Lungu’s failure to tackle corruption made his electoral defeat an inevitable reality). At his peak, his online live rallies would attract as many as 30,000 viewers on a single platform – a feat that no Zambian influencer, artist, or media institution has ever achieved.

Whatever his intentions and motivations, Seer 1, through his persistent rantings against the governing elites, made two significant contributions to Zambians’ struggle to rid themselves of a repressive regime and achieve political change. First, he raised the levels of civic awareness in a population that is prone to clerical mobilisations and where political messages are sometimes more effective when delivered in a religious language. Second, he exploited Zambians’ deep connection to faith to generate a national psyche of expectation that president Lungu would, regardless of whatever attempts he makes to stay in power, lose the election. In an environment in which the governing party had looked invincible insofar as their removal from office was concerned, the Nigerian prophet presented God as a proud partisan who was set to deliver a miracle: the destruction of the invincible via the ballot!

Honourable mentions

Those who deserve honourable mentions include Linda Kasonde, whose Chapter One Foundation successfully obtained a court order that stayed the government’s shutdown of social media platforms on election day; four University of Zambia lecturers – O’Brien Kaaba, Felicity Kayumba Kalunga, Pamela Sambo, and Julius Kapembwa – who provided regular, highly regarded and informed public commentaries on topical issues, which shaped public understanding and served as a critique of the state of governance under Lungu; civil rights activist Laura Miti whose effective use of social media contributed to high levels of civic awareness and fostering understanding about the importance of voting; and two civic institutions, namely the Christian Churches Monitoring Group (CCMG) and Governance, Elections, Advocacy, Research Services (GEARS), which deployed thousands of monitors in nearly all the 156 constituencies and conducted a parallel vote tabulation that captured the election results at polling station level, ensuring that any manipulation would be exposed.

One Response

Dr. Sishuwa, l don’t see Pilato here & ofcourse yourself sir ( you will not be blowing your own trumpet cos the majority Zambians know & are very appreciative of the bravity you showed during PF’s reign of terror).