Zambia transitioned from a one-party state to a multi-party democracy in 1991. This transition entailed a change in Zambia’s constitution to reflect the ideals of a plural democracy in which rights and freedoms were entrenched and an attempt to the remove the cult of the all-powerful political leader was made. Zambia now stands on the cusp of yet another constitutional review process, the sixth of its kind since the country gained independence in 1964.The Constitutional Amendment Bill No. 7 0f 2025, like its predecessor the Constitutional Amendment Bill No. 10 of 2019, threatens to take the country down the dark path of constitutionally entrenched dictatorship. Constitutionalism is the limitation on government power through the Constitution. I would argue that the reason constitutionalism has largely failed in the country is due not only to failed constitution-making processes, but also due to a lack of temerity on behalf of the judiciary. This has forced the people of Zambia to save themselves time and time again.

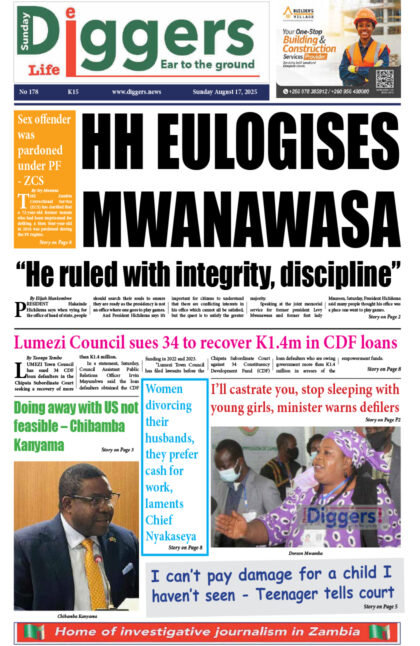

As I write this, today is Africa Freedom Day 2025. Ironically, on the eve of Africa Freedom Day, the Government gazetted the Constitutional Amendment Bill No. 7 of 2025 which will rob the people of Zambia of their rights and freedoms by increasing the already extensive powers of the Executive and the ruling party in Parliament. It is not an exaggeration to say that this Bill is even more frightening than Bill 10 of 2019. What’s worse is historically, when previous governments have tried to reverse our democratic gains, they at least put up a semblance of national consultation structure: President Kaunda held a national referendum in 1969 ahead of the 1972 amendments, other governments held national constitutional review assemblies such as the National Constitutional Conference under President Levy Patrick Mwanawasa, and the National Dialogue Forum under President Edgar Chagwa Lungu.

To put it mildly, the current government is not only rushing the process but insists that there is no need for broad-based consultation because the clauses they are proposing are “non-contentious”. Some of these so-called “non-contentious clauses include the following:

1. The proposed Article 81 scrapping the provision that provides that Parliament should be dissolved three months before the general election. The safeguard under the current Article 81 of the Constitution ensures that the government cannot sneak in pieces of legislation that will favour them during the election. This provision saved Zambians from the enactment of Bill 10 in 2021 because the ruling party did not manage to pass the Bill before Parliament was dissolved ahead of the 2021 general elections. Given the fact that the current ruling party has an almost two-thirds majority in Parliament, the ruling party appears to have the power to pass or change any law, which requires a simple majority, or to amend the Constitution which requires a two-thirds majority. Under the proposed Article 81(3), Parliament would be dissolved a day before the general election. It is worth bearing in mind that the current Constitution under Article 81(10) allows for the President to recall Parliament due to a state of war of emergency so it is unclear why Parliament should not be dissolved three months before the election.

2. Article 57 of the Constitution may be repealed and replaced by a new Article 57 under which by-elections would now only apply to independent elected MPs, and independent Mayor, a Council Chairperson of Councillor. Regarding vacancies of party-sponsored MPs, the proposed new Article 72(8) provides that “a political party that sponsored the member who held the seat shall elect another person to replace that member”. This potentially means that political parties can force out democratically and popularly elected candidates and replace them with individuals who are party yes men who have no real constituency.

3. Also worrying is the repeal and replacement of Article 58 of the Constitution to increase the number of elected MPs to 211 seats from the current 156 seats. It also makes an additional number of seats for women (up to 20 seats), youth (up to twelve seats) and disabled persons (up to three seats) whom are all to be “elected” by proportional representation as prescribed in an Act of Parliament. Until that statute is enacted, we do not know how the political parties to be represented in the proportional representation election will be elected. There are also the additional ten nominated MPs under Article 68(e). What we do know is that the ruling party will typically have the majority of parliamentary seats in a general election. When you add to that the number of proportional representation seats and nominated seats, all of which have voting rights, it makes it more likely for the ruling party to have an in-built two thirds majority. Not to mention the delimitation exercise by the Electoral Commission, from which the increased number of constituency seats has purportedly been derived, was shrouded in secrecy.

4. Like MPs, under the proposed Article 158(1) of the Bill, in the case of a vacancy of an elected Mayor, Council Chairperson, or Councillor of a local authority, the political party that sponsored them may elect a replacement. Again, this potentially means that a popularly elected local government official can be forced out at the whim of their sponsoring political party.

5. The Proposed Article 176(3) of the Bill reduces the qualifications of the Secretary to the Cabinet from the current requirement of having ten years’ experience at Permanent Secretary level or equivalent rank to only five years of such experience. This diminishes the weight and depth of experience required of the Civil Service’s most senior office holder.

6. Article 52 of the Bill proposes the removal of corruption and misconduct as the basis on which a court can disqualify a nominee for election which is very worrying indeed. It appears that now any basis is permissible for a court to disqualify a candidate. This provision appears to be targeting the eligibility of President Lungu to stand in the general election. It now means that a court can disqualify a candidate on any basis, it is no longer confined to corruption or misconduct.

There are other troubling provisions of the Bill, but in my opinion the above are the most egregious and contentious ones.

Undoubtedly, the Courts will be called upon again to adjudicate over whether these proposed provisions adhere to our constitutional values, principles, and the very fabric of our democracy. However, if the previous case in which the Constitutional Amendment Bill No. 10 of 2019 was challenged is anything to go by, our courts may not rise to the occasion. Subsequently, the buck stops with us, the people of Zambia for whom the Constitution is created. To quote a Zambian legal luminary:

“The country of our dreams should be a country that is known for unity, liberty, tolerance, and rule of law. It should be a country where the citizens and not the politicians are sovereign.”

Linda Kasonde is a lawyer and activist. She is also a 2014 Archbishop Desmond Tutu Leadership Fellow.

One Response

To the point. Let’s not go for constitutional amendments.