Appearing on Radio Christian Voice’s Chat Back programme last week, opposition United Party for National Development (UPND) leader Hakainde Hichilema revealed that mining companies in Zambia have told him that they cannot wait for him to ascend to power because they see him as someone who will clean up the mess in the sector. ‘“The mining companies are talking to us; they are saying ‘HH we are waiting for you to come, we are waiting for you’”, he said. The UPND leader criticised as chaotic the new mining tax changes proposed by the government in this year’s budget. He however stopped short of explaining what exactly is wrong with the proposed mining taxes, what his administration would have done differently had he been in power, and why he thinks mining companies, generally seen by many Zambians as not paying their fair share of taxes, want him elected. Before I discuss the meaning and implications of Hichilema’s extraordinary disclosure, I would like to go back to an article I wrote in this column on 25 December 2017 under today’s title. I seek the reader’s indulgence to publish it in full and unchanged because it is important to the point I wish to make next week, when I plan to examine in greater detail Hichilema’s jaw-dropping ineptitude on the mining issue.

…

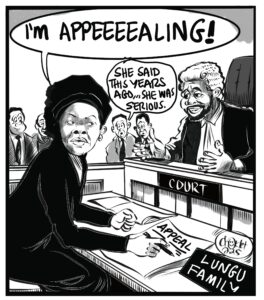

On 17 December 2017, opposition United Party for National Development (UPND) leader Hakainde Hichilema appeared on Sunday Interview, a Zambia National Broadcasting Corporation (ZNBC) television programme hosted by Grevazio Zulu every Sunday evening that typically consists of an in-depth, one-on-one 60-minute interview with a prominent guest. Hichilema’s rare appearance on the public broadcaster followed the UPND’s successful request to ZNBC that the opposition leader be granted an opportunity to feature on the show in order to “address some key issues affecting the nation”. Zambians who had hoped that Hichilema would use the platform to share his vision for the country and explain why anybody deserves to be led by him were left disappointed. The UPND leader failed to reveal any enthusiasm or sense of outrage, gave a series of vague and superficial replies to the interviewer’s questions, condescendingly berated his host as an ignorant worker who did not understand this or that, insisted on the legality of the court challenge to Lungu’s election without providing any political reason for continuing with the contest, and argued that he is rich because he has worked hard smartly.

To be sure, Hichilema did promise to increase maize prices and keep mealie meal prices down but stopped short of explaining how exactly he would pay for these moves. He also mentioned the recently acquired $42 million fire trucks and the inflated cost of public procurement, but only in passing. Unbelievably, he hardly mentioned anything in relation to Zambia’s swelling debt, a very odd position for someone who frequently proclaims himself to be an economist. All in all, Hichilema missed a huge opportunity to talk about the real issues – poverty, inequality, poor services, corruption, unemployment, the erosion of the rule of law, etc. – that affect majority Zambians, to critique the performance of the governing Patriotic Front on these concerns, and to project his own ability to handle them better. Even though he was not asked, any effective politician with skilled advisors knows how to answer a question but shift the answer towards delivering the substantive message. In Hichilema’s case, there was no message and throughout the ZNBC interview he seemed to be seriously in need of some ideological, strategic and tactical sense.

Hichilema’s unsatisfactory performance on the Sunday Interview underlines two of his major weaknesses as a political leader seeking Zambia’s most coveted elective public office. The first is a longstanding and costly failure to connect with the majority of ordinary Zambians. This is a weakness that his political opponents like Lungu have repeatedly exploited and probably one that arises from the feebleness of Hichilema’s political character. Other than having money (the origins of which are open to question), there is absolutely nothing to the man, politically speaking. He has no magnetism or charisma, he lacks a political strategy, he finds it impossible to identify with the majority of Zambians who are poor (by his own admission, he is rich because he has worked hard smartly, and by implication, the majority of Zambians are poor because they are lazy and not smart – so how the hell can he speak and act for them?) and he lacks the rhetorical skills necessary in politics. Perhaps his greatest weakness is that he did not enter politics as an individual with a political axe to grind, but saw an opportunity with the death of UPND founding president Anderson Mazoka and took it.

The second is Hichilema’s enduring inability to explain clearly his motivations for seeking public office and power. Why does Hichilema want to be President of Zambia? This is a question he needs to articulate a convincing answer to. What exactly does Hichilema offer Zambians other than the fact that he is not Edgar Lungu? On the evidence he has given so far, it appears that the answer is very little. Hichilema has no distinctive political positions nor any real desire for genuine radical emancipatory politics the country is badly in need of. His politics appear to be entirely anchored on reminding us about the tragic ineptitude, unlimited greed and unscrupulousness of President Lungu, but Lungu’s weaknesses must never be allowed to become Hichilema’s main strengths. Politics in Zambia is not only the activities and opinions of Lungu.

There exist a wide variety of pressing concerns on which Hichilema is silent. For instance, controversial estimates by a High Level Panel Report on Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs) indicate that Zambia accounts for 65 per cent of Africa’s IFFs, largely ‘facilitated by a global shadow financial system comprising tax havens, secrecy jurisdictions, disguised corporations, anonymous trust accounts, fake foundations, trade mispricing, and money laundering techniques’. What is Hichilema’s position on this important issue and how does he plan to curtail this massive flight of capital from Zambia’s economy – money that could otherwise be used for poverty alleviation and economic growth?

What would be the approach of a Hichilema presidency towards mining investment? This sector is absolutely not only crucial to Zambia’s economy but one that Hichilema was closely associated with. Questions remain about his relationship to the privatisation of the mines and the mining corporations themselves. What does he think about the poor wages and living conditions of black Zambian mineworkers on the Copperbelt and in North-Western Province today, especially when seen against the lavish earnings, housing and social facilities of their white counterparts? How exactly does he intend to ensure that the exploitation of Zambia’s natural resources benefits the country as much as investors? Having ascended to the UPND presidency in 2006, Hichilema has had ample opportunity to explain his political vision and tell Zambians why he became a politician, yet he has not done so. The UPND’s ten-point plan is, to put it mildly, short on answers. Its formula simply copies PF policies by promising more. How will these policies be enacted and paid for? Zambians deserve clear responses.

Zambia’s economic malaise and slide into political authoritarianism require a robust and effective opposition. In many ways, Hichilema’s failure to provide such an opposition makes him a great friend to Lungu because a more competent leader of the opposition would have delivered Zambians from the failed PF experiment a long time ago. In a space of only three years, for instance, Lungu has effectively destroyed the vestiges of autonomy in all state institutions outside the executive arm of government for the purposes of establishing an authoritarian regime and a slide into a fearful dictatorship. The President has carried out this task with considerable ease, impunity and skill (albeit of a criminal variety), employing a line of political rhetoric and well-concealed hypocrisy that went unrecognised until it was far too late. As leader of the opposition, Hichilema was supposed to identify, analyse, reveal and oppose Lungu’s project from the outset. In this regard, Lungu has been very competent in revealing Hichilema’s incompetence, ineffectiveness and impotence.

In some ways, Lungu and Hichilema need each other. Lungu’s failures encourage many Zambians to support Hichilema even though he offers little. Hichilema’s weaknesses and inability to mobilise voters around wider concerns or shared elements of a national programme enable Lungu to remain in power largely undisturbed. They appear as two mediocrities, each benefiting from the other. Lungu has consistently demonstrated over the last three years that he is not a leader and he only appears to be one because the opposition is extremely weak. Hichilema and the UPND, for instance, have failed to address Lungu’s manifold inadequacies, making him seem more competent than he is. In turn, Hichilema benefits from the incompetence of Lungu, doing nothing as he simply waits for Zambians dissatisfied and angered by Lungu’s rule turn to him as the default alternative.

Yet if there is anything that Hichilema has demonstrated over the past decade, it is that he is not a leader of the future or a credible opposition figure of the present. He is yesterday’s man. However, thanks to the waves of present weaknesses and mediocrity in Zambia’s politics, a man whose politics and personal qualities are largely unknown may well become Zambia’s next president. He is getting so confident of this prospect that he now comes across as someone who must be President of Zambia simply because it is him. In a recent interview with News Diggers, Hichilema gave the example that when he was at Coopers and Lybrand Zambia (later Grant Thornton), he was several times elected as the firm’s chief executive officer for 13 years, and seemed genuinely puzzled that the more than five million voters of Zambia are not looking for the same leadership qualities that so impressed the few shareholders of Coopers and Lybrand.

Hichilema should, however, be warned that he cannot rely on the passive support of voters. It is even possible, if he is not careful, that an upstart presidential hopeful such as Chishimba Kambwili may reach State House earlier than him. The UPND leader needs to develop an affective political strategy and a clear vision, one that resonates on a very phenomenological level with majority Zambians, especially the common man. Although he almost won in 2016, many of those who supported him were not UPND members; they did so only because they opposed Lungu’s continued misrule. There is no guarantee that the same voters will support Hichilema or the UPND in a future election. The fate of the Movement for Multiparty Democracy should be a lesson to the UPND about how quickly political support can evaporate. Zambian voters do not have a history of party loyalty and there is no guarantee that the 47.6 per cent who voted for Hichilema in 2016 would do so again tomorrow.

Feedback: [email protected]; @ssishuwa