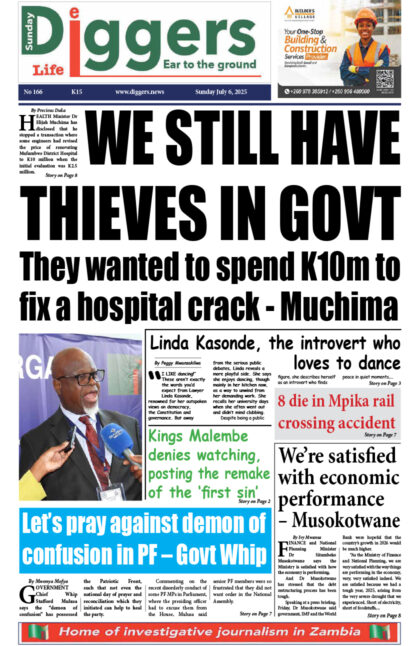

In response to my column, ‘Class of 2020: Zambians who gravely disappointed last year’, the board of Chapter One Foundation took issue with my inclusion and criticism of the actions of its executive director, Linda Kasonde. In an article dated 28 January 2021 and signed by Sara Longwe, the board chairperson, the advocacy organisation exercised its right to reply and thus made an important contribution to fostering a culture of reading and written debate in Zambia.

I welcome the response from Chapter One Foundation and take my hat off to them for acknowledging that they are not immune to public criticism. Other individuals and institutions operating in the public sphere should consider adopting the same policy because it is healthy and encourages open discussion of some of the most salient issues of our time. Even for me, the idea behind writing in the public domain is to encourage open engagement. In fact, I am disappointed that more people do not criticise what I put out. Readers should freely question my views and positions on any given subject. Their feedback may either broaden my perspectives or cause me to counterin a manner that both raises the quality of public debate and promotes wider understanding of the issues being discussed.

I believe that those who welcome praise must also accept criticism. Having claimed and exercised my freedom of expression, I am only all too aware of the right of others to exercise the same free speech on any matter, including when commenting on my public commentaries. Being human, it is natural that we will have varying lines of thought. I do believe, however, that it is only through many conversations that we can reconsider our positions, challenge our assumptions, question our convictions, and come to appreciate our own ignorance. Of course, the notion of content-based discussion seems like a tall order in today’s polarised Zambia, where any criticism of the government is deemed as support for the opposition, and vice-versa. We must get rid of this binary divide. It is unproductive, curtails meaningful interactions, and draws attention away from the real issues.

I also wholeheartedly and warmly welcome the invitation by Chapter One Foundation to engage further on the matters I raised in my column. To this effect, I look forward to receiving a formal invite on a date and at a venue appointed by them. I am open to a web meeting too!

I am keen to learn from them how they process decisions on crucial national issues and to inform them that my criticism of the public actions of their executive director is nothing personal. It is about the damaging cost of un-strategic litigation on crucial national issues. As a matter of fact, I respect and appreciate Linda Kasonde, but I insist that she messed up big time for the reasons I outlined in the article that attracted the Foundation’s reply and which I develop further below.

So, let us unpack Chapter One Foundation’s response on a paragraph-by-paragraph basis. The civic institution starts its reaction to my article with a disingenuous attempt to manufacture a position for me on the roots of my criticism of Kasonde’s actions in 2020.

“Chapter One Foundation has noted that its Executive Director, Ms. Linda Kasonde, has been placed on Dr. Sishuwa Sishuwa’s list of ‘Zambians who gravely disappointed’ in 2020 which appeared in the 26th January 2020 edition of News Diggers newspaper. The critique arose out of a decision that Chapter One Foundation took to challenge the 2020 voter registration and national registration card registration exercise in the Constitutional Court.”

Comment: Did Chapter One Foundation really understand my article? Had they done so, they would have noted that my rebuke of Kasonde’s conduct had nothing to do with her actions to challenge the selective issuance of mobile National Registration Cards as being unconstitutional and the decision of the Electoral Commission of Zambia (ECZ) to conduct the registration of voters in 30 days only as being contrary to the constitutional mandate of the electoral body. My criticism was based entirely on her decision to amend her original cause of action in the Constitutional Court to ask for a third relief over and above the initial two: that the decision by ECZ to ‘disallow currently registered voters from voting in the 2021 general election is unconstitutional and therefore null and void.’

I then showed how this specific action closed the possibility of halting the process initiated by ECZ. In effect, Kasonde’s amendment prevented the immediate relief being won in a lower court, one that could have gained interested people more time to mount a final assault on the matter and ultimately stopped the electoral body from going ahead with its plans. By claiming that my criticism of the actions of its executive director “arose out of a decision that Chapter One Foundation took to challenge the 2020 voter registration and national registration card registration exercise in the Constitutional Court”, the board of Chapter One Foundation either genuinely misread my article, is deliberately misleading readers, or is unforgivably ignorant – and whichever one it is, it is unacceptable from a group of people responsible for providing critical direction, advice and oversight to the running of the institution.

The board: “Chapter One Foundation was the first organisation to challenge both registration processes in August 2020. We did this in line with our mandate to promote and protect human rights, the rule of law, and constitutionalism in Zambia.”

Comment: Here, the civic body was making a poor attempt at concealing the sequence of events. Yes, Kasonde might have gone to court early, but it was her subsequent amendment and refusal to adjust this that matters here. For the sake of transparency, it is important to show the sequence of events in a clear manner that misleads no one and is easy to follow. On 3 August 2020, Kasonde approached the Constitutional Court with two legal challenges: that the selective issuance of mobile National Registration Cards by the Ministry of Home Affairs was unconstitutional and that ECZ’s decision to conduct the registration of voters in 30 days only was contrary to its constitutional mandate. The case was filed on 3 August 2020 and has not been heard to date.

The second case was filed urgently in the High Court on 28 August 2020 by the main opposition party, the United Party for National Development (UPND) who, among other things, challenged the Commission’s decision to discard the existing voter’s register as being against the Electoral Process Act No. 35 of 2016. The third case was filed in the High Court on 15 September 2020 by a quartet of civil society activists led by Chama Fumba, popularly known as Pilato, who sought to halt the decision to discard a valid and lawfully established voters’ register on the ground that this action violates the cited Electoral Process Act.

While the first two cases have suffered delays, the one filed last was dismissed by Lusaka High Court judge Gertrude Chawatama on 29 September 2020 on the ground that the UPND had raised a similar matter before a different High Court judge, Mwila Chitabo. Justice Chawatama ruled that granting the activists the reliefs they sought before the UPND case was determined might lead to conflicting decisions and ‘bring the integrity of this court into disrepute’. Two days later, on 1 October 2020, the UPND case was itself postponed indefinitely when justice Chitabo ruled that he would only hear the matter after the determination of similar pleadings filed before the Constitutional Court by Chapter One Foundation. A few days earlier, Kasonde had sought leave to amend her petition before the Constitutional Court in order to include the third ground: “a declaration that ECZ’s decision and intention to disallow currently registered voters from voting in the 2021 general election and future elections is unconstitutional and, therefore, null and void.”

After the Constitutional Court approved the application on 1 October 2020, the High Court’s Judge Chitabo – with unprecedented judicial efficiency – used this development in the superior court to indefinitely adjourn the UPND case on the same day! I do not know what exactly motivated Kasonde to make the problematic amendment when both the UPND and Pilato cases had already raised similar pleadings in the High Court. What I know is that itis this lack of coordinated action between civil society and the opposition that has led to the present situation where both the UPND’s case in the High Court and that of Chapter One Foundation in the Constitutional Court have become moot. In the meantime, the ECZ has implemented its plans and produced a new voters’ register, one that the commission is refusing to subject to any independent audit.

Now, the board of Chapter One Foundation must answer to the substance of my rebuke of the actions of their executive director: why did Kasonde, acting in the name of a public interest strategic litigation, amend her case to include a part that gave the lower court the escape route from offering the immediate relief that could have halted the ECZ’s manoeuvres? On the day Kasonde was granted leave to amend her original petition by the Constitutional Court, even before the substantive issue was dealt with, the High Court used that development as a basis for indefinitely adjourning the UPND petition. It is therefore impossible not to argue that the High Court was given a lifeline by Kasonde’s action. Without the action from Kasonde, the lower court would have struggled – as it did between August, when both cases were filed, and October – to find a valid excuse to adjourn the case indefinitely. By making the amendment, Kasonde delivered them the reason. This is the crux of the matter. No one is challenging their mandate.

Chapter One Foundation has no right to evade the essence of my arguments and rebuke by creating strawmen. Kasonde and the civic board have every right to go to court, but it is not enough for them to justify their actions on the ground that they are following their mandate. Their mandate does not supersede public interest. It should only and always be exercised in furtherance of public interest. In other words, their right to litigate does not give them the licence to injure public interest. As I stated in my originating article, by making the amendment and refusing to withdraw it when she was asked to do so, Kasonde effectively injured the rights of the same people – not the rights of her organisation – whose interests she was seeking to protect.

Let us pull the next paragraph from the board of Chapter One Foundation:

“Dr. Sishuwa has issue with the fact that we opted to go to the Constitutional Court to seek redress instead of opting to file a judicial review application in the High Court which he states affords greater avenues for interim relief. In our view, there is no remedy that the High Court can give that the Constitutional Court cannot give. Unfortunately, as the case is still in court, we are unable to discuss the merits of the case save to say that we took out our petition to defend our constitutional right to vote, a claim which cannot be remedied in the High Court.”

Comment: First, I did not dispute the fact that the Constitutional Court can give all the reliefs that the High Court can provide. The issue was about where one can get an effective remedy, which in this instance would have meant a decision that arrests the process initiated by ECZ or stops an administrative action from being implemented, one whose consequence would have been the removal from the existing register of people who may not have the opportunity to register again before the general election In any case, the ECZ’s decision to abolish the permanent register rather than updating it, as required by law and as has been done in each election since 2005 when it was first created, violated a parliamentary statute, particularly the Electoral Process Act Number 35 of 2016, not Zambia’s constitution. This type of violation is typically a cause of action for judicial review.

Second, I never discussed the merits of Kasonde’s arguments in her petition before the Constitutional Court nor questioned the wisdom of using an organisation as the litigant to defend the right to vote. My rebuke of her conduct in 2020 rested solely on her demonstrated poor judgement on a very specific issue: the previously cited amendment to the original cause of action that she raised in the Constitutional Court, which had profound adverse consequences. Strategically, and given both the record of the court that she approached on that specific issue and the wider political climate within which the Judiciary is operating in Zambia today, her action was ill-advised. It is not enough to go to court. One must have a clear strategy behind the choice of the level of court approached.

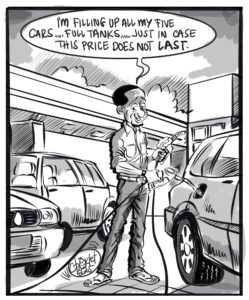

The ECZ’s admission that the government had not provided it with sufficient funds for voter registration implies that the exercise was not going to be completed to the best satisfaction of even the Commission itself. What does this mean in political terms? That stopping these administrative actions would have contributed to eliminating possible electoral violence and guaranteeing a credible electoral process. What was at issue was the need to move with speed to prevent the electoral commission from going ahead with its intended actions. The rest of the constitutional questions could have been raised separately or later. This is why the judicial review option in the High Court was important to securing urgent interim reliefs that could have halted the ECZ’s plots. If this remedy is so readily available in the Constitutional Court, why has Chapter One Foundation failed to secure it? A petition in any court is successful to the litigant only when they have achieved their objective. Now that the new voters’ register has been produced and thousands of people have been disfranchised, can Kasonde and her organisation declare that they have achieved their objective of going to court to make that specific amendment?

The board of Chapter One Foundation again: “One of the advantages of having an action declared unconstitutional by a court of law is that the action that is subject of the petition will be rendered null and void; meaning that the action being challenged will no longer be legally binding. Also, as a court of first and final instance, taking the matter to the Constitutional Court was the quickest way of ensuring that the issues were determined before the 2021 general elections. Cases in the High Court are subject to appeal which may delay the determination of the case.”

Comment: In this paragraph, one sees the naivety and poor judgement that may have guided Kasonde’s actions when making the specific amendment to the Constitutional Court. If the board and Kasonde had familiarised themselves with the current practice and precedence coming from the Constitutional Court, they would have known that even the declaration of an action or decision as unconstitutional does not translate into the reversal of such an action or decision. The recent case of former Roan constituency MP Chishimba Kambwili is illustrative here. In this matter, the court confirmed that if a horse has already bolted, it is too late for it to intervene. Despite finding that the Speaker of the National Assembly Patrick Matibini acted unconstitutionally when he declared Kambwili’s parliamentary seat vacant, the Constitutional Court refused to grant the ex-lawmaker the relief that he had asked for: “a declaration and order that the ruling of the Speaker dated 27 February 2019 is null and void ab initio.”

By refusing to invalidate the Speaker’s action, the Court sanctioned the violation of the Constitution and commission of an illegal act contrary to the express provisions of the Constitution in Article 1(2), which states that “an act or omission which contravenes this Constitution is illegal.” In effect, the Constitutional Court sanctioned the illegality and gave an incentive to the Speaker of the National Assembly, or any other public official, to breach the Constitution with impunity. It does not help that the Court referred to the fact that another MP had been elected to replace Kambwili as potentially creating a constitutional crisis. This position communicates the idea that unlawful violation of the Constitution is fine – one must simply act fast enough and secure their unlawful position in a manner that would cause political disruption before the court renders its judgment. The court would then tailor its decision to accommodate the illegality, thereby undermining the supremacy of the Constitution. Given this very recent history, what possible relief is the board of Chapter One Foundation expecting to get from the ConstitutionalCourt, realistically speaking? Are they serious when they say that “One of the advantages of having an action declared unconstitutional by a court of law is that the action that is subject of the petition will be rendered null and void”? Is the board of Chapter One Foundation seriously expecting the court to render the action of ECZ as unconstitutional and declare that the commission must restart the voter registration process?

Let us assume, for argument’s sake, that the court, after hearing the matter, grants Kasonde the reliefs she is seeking including on the crucial amendment she made in October but then this happens after the existing voters’ roll has been abolished and a new one created, or the general election has taken place, with the president and members of parliament elected and sworn in. Is it the legitimate expectation of the board and Kasonde that the court would declare the new voters’ register as invalid; that the whole process is null and void and that these actions – the creation of a new voters’ register and results of the elections – be set aside because the voters’ register was faulty, and voters were disfranchised? Really? The board and Kasonde should know better how our courts behave in matters like this – as the cited case of Kambwili has shown.

The board’s explanation that they went to the Constitutional Court because it offered ‘the quickest way of ensuring that the issues [it raised] were determined before the 2021 general elections’ does little to weaken my argument that, in this instance, the High Court was a better option for seeking urgent reliefs, as her own actions in the Concourt have proved. I applaud the fact that Kasonde and Chapter One Foundation were the first to go to court, but the matters for which they went to court were not the urgent matters at issue here. The board is putting a big distance between her originating cause of action and what was at issue. The issue was the amendment to her cause before the Constitutional Court which was then used by the High Court to undermine proceedings before it.

By refusing to withdraw the amendment as requested, Kasonde and the board preserved the static status of their matter before the superior court. But where are we now? Trial in their case has not even commenced, yet a new voters’ register is out. Is this not the same outcome that Chapter One Foundation had planned to prevent? By the time Kasonde gets her “trial” in the Constitutional Court, that is if the matter is not dismissed for being an academic exercise, the horse will have already bolted! If time has not confirmed their poor judgement on this specific issue, can Kasonde and the board of Chapter One Foundation account for how their actions translate into victory NOW or before the 12 August general election? Can they explain how the amendment that they lodged in the Constitutional Court in October 2020 and refused to withdraw when asked to do so will benefit anyone, given where things are at?

Today, what is the value of them being in the Constitutional Court on the matter? I would like to believe that they did not go to court for an academic exercise or merely to give a signal to donors about how their funds are being utilised.They did so in the public interest because there were actions from the government that needed to be stopped. In this instance, it was important that the ECZ was stopped in its tracks from abolishing the existing voters’ register, producing a new one and creating the possibility of electoral gerrymandering that would effectively guarantee President Edgar Lungu victory. By amending their initial petition and refusing to change course when the damaging consequences of their action were shared with them, Kasonde and the board effectively paved the way for this outcome. If Lungu and the PF ‘win’ re-election thanks to a dubious voters’ roll, Chapter One Foundation might as well claim credit for that outcome, for they would have played a significant role in facilitating it. Whatever they intended, outcomes matter more than intentions. Kasonde and her organisation should acknowledge that they made a fatal miscalculation – though they do not appear to comprehend the magnitude of their error. If they can stubbornly defend failure, thenthey are not permeable to reason.

The board: “Chapter One is all for fair comment however, we think that Dr. Sishuwa’s article makes a number of worrying assumptions that we feel that we must address: The assertion that Ms. Kasonde acted as a “lone wolf”.Chapter One Foundation consists of a team of professional and qualified staff, who makes decisions collectively and did so in this case.”

Comment: My original argument is about Kasonde’s role through Chapter One Foundation, as she is the best-known member and public face of the organisation. It is not a comment on Kasonde’s persona or the internal workings of the organisation she represents. In the originating article, I stated that “If she is to succeed in her advocacy work, which includes efforts to defend democracy, Kasonde would do well to learn, urgently, the value of building consensus with other progressive forces, especially when dealing with important national matters. By nature, advocacy is collaborative and requires the subordination of one’s ego to the collective, no matter how informally constructed. It is dangerous to retain a lone-wolf kind of attitude when one needs to work with other people to determine the most effective strategy for achieving certain goals and the best course of action on issues of greater public interest”.

This is the context in which I used the term ‘lone wolf’, one that had nothing to do with Kasonde as a person or the organisation’s internal operations and culture. I insist that when Kasonde, in her representative role as chief executive of Chapter One Foundation, failed to work with other people pursuing the same objectives outside her organisation, she exhibited a lone-wolf kind of attitude. Put differently, Chapter One Foundationacted as a lone wolf through Kasonde.

I do not know the quality of staff that Chapter One Foundation has. Since the organisation presents itself as a civic body that seeks to protect human rights, defend and promote constitutionalism ‘through strategic litigation and advocacy’, I can only imagine that they have employed, among others, individuals with specialised training in human rights and constitutional law. I am therefore disappointed that such a ‘team of professional and qualified staff’ not only committed a fatal strategic error of judgement in relation to the specific amendment at hand but also lacks the courage and humility to acknowledge this glaring point even when presented with evidence. If the board and the ‘team of professional and qualified staff’ sanctioned both the un-strategic amendment and the refusal to withdrawal it, then I sincerely apologise for not labelling the rest of the organisation disappointments as well, because such a scenario would confirm that more people were to blame than Kasonde.

The board: “As a team, we decided that the case had merit and we decided to file it in August 2020.”

Comment: No one is disputing the possibility that legally and constitutionally, there might be merit in those two initial issues for which Kasonde and the Foundation filed their petition in the Constitutional Court. The issue was about how their specific amendment, in early October 2020, on plans by ECZ to discard a valid and lawfully established voters’ register gave the High Court reason to stay proceedings on the ground that a superior court was dealing with a related matter.

The board: “Dr. Sishuwa neglects to state that, as the first organisation to commence an action, we were the first to reach out to the lawyers and litigants who had commenced the two subsequent actions in the High Court to see if we could work together. Our efforts at collaboration did not yield any results. By the time that they came back to us seeking to work together on a completely new judicial review court case at the end of 2020, our case had advanced to near trial stage.”

Comment: I am not disputing the consultations Kasonde made with other lawyers in relation to the two causes of action she filed on 3 August 2020. It is the amendment that I said was the problem because it gave the High Court the opportunity to decline hearing any applications for quashing the ECZ’s schemes using the pretext that Chapter One Foundation had a related matter before the superior Constitutional Court. Which lawyers did she consult before making the amendment in October? When those concerned about the consequences of her amendment reached out to her the same month, neither voter registration nor trial in her matter had started, so there was still time to stop the electoral body’s manoeuvres. Why did she refuse to remove the amendment on a specific matter? This is what is at issue and needs to be addressed.

And what constitutes ‘near trial’? If it means that the court was about to start trial, where is the proof? Was a date set for trial? Was a timetable given to Kasonde and the Foundation? Even if trial had started by December, that would have been several weeks into the voter registration exercise and the process of abolishing the voters’ register. How long was trial going to take? This is a court that has proven itself to be very unreliable when it comes to delivering decisions on time. Therefore, in a case where one wanted an action to be stopped immediately, was it really wise to rush to the Constitutional Court? If it was not, then doesn’t this confirm the poor judgement I was talking about?

The board of Chapter One Foundation: “It is worth noting that [it] is likely that our case would have been at trial stage now had it not been for the untimely passing of the judge presiding over our case, Justice Enoch Mulembe, in December 2020. The case has now been allocated to a new judge.”

Comment: Kasonde and Chapter One Foundation went to court in August 2020. The judge died over four months later, on 17 December 2020, when hearing in their matter had not even commenced. Had it not been for the joke of the four-day extension that ECZ implemented following the expiry of the 30-day registration window on 12 December 2020, Justice Mulembe would have died after the registration had already closed.

The board: “Dr. Sishuwa argues that the reason that the other litigants failed to proceed with their cases in the High Court is because Chapter One Foundation had filed a case in the Constitutional Court, a superior court.”

Comment: This is not what I said. I said the case of the other litigants before the High Court failed to proceed because of her October amendment. I invite the board to reread my originating article, more carefully. The issue is that when Kasonde was granted her wish to amend her original petition in the ConCourt, the High Court used that amendment to escape stopping the ECZ from manufacturing a potentially questionable register of voters. We are now saddled with a new voters’ register because Kasonde did not give us the possibility to stop that action. I am not arguing about the other things she raised.

The board again: “Chapter One Foundation simply asserted its constitutional right to defend the Constitution. Judges have the discretion to grant or deny leave (permission) to issue judicial review proceedings – there are no guarantees that leave will be granted. No leave is required to commence proceedings in the Constitutional Court. A person can take out a petition in the Constitutional Court to defend the Constitution as of right.”

Comment: It is true that judges have the discretion to grant or deny permission to commence judicial review proceedings. However, the discretion is not absolute. It is regulated by the factors stated in the law regulating judicial review proceedings, including establishing a prima facie case suitable for a full trial. Once these factors are met, a court cannot justify refusal to grant leave. If Kasonde and Chapter One Foundation are being honest, they would admit that the reason they did not pursue judicial review in the first instance is because they went to court to challenge the constitutionality of selective issuance of national registration cards and the failure of ECZ to conduct voter registration on a continuous basis, matters which are substantially different from what the petitioners included in the October amendment. The amendment sought to remedy the arbitrary disregard of legislative provisions which cause of action is suited for judicial review proceedings. If what the board alleges were true, the High Court would not have waited for Kasonde’s amendment to knock out the judicial review matter commenced by the UPND on a technicality.

The board: “Dr. Sishuwa also neglects to state that the Electoral Process Act has been in effect since 2016 and nobody had stepped forward to challenge the manner in which the right to vote has been violated until after Chapter One Foundation did.”

Comment: Although the Electoral Process Act has been in existence since 2016, the decision by ECZ to create a new register and effectively de-register registered voters was only first announced on 12 June 2020. I do not suppose that the Foundation wished for someone to challenge a decision that had not yet been made. In any event, Chapter One Foundation’s original case – as filed in the Constitutional Court on 3 August 2020 – did not include a claim relating to the abolition of the existing voters’ register. What this means is that the UPND, and not Chapter One Foundation, was the first litigant to challenge the decision of the ECZ to discard the existing voters’ roll. Further, why choose a court that takes a century to pass a verdict when what is needed is action now?

Here is the board again: “The assertion that Ms. Kasonde and Chapter One Foundation should have deferred to the lawyers in the other cases. As already mentioned, Chapter One Foundation works as a team and that we had earlier reached out to the other litigants in the other two cases. Dr. Sishuwa asserts that the position taken by the litigants in the other two cases was the more correct way to seek redress from the Courts of law.”

Comment: What in my view makes the judicial review process preferable are the following factors: the cause of action emanated from the blatant disregard of a statutory provision by the ECZ; evidence of the slow pace at which Constitutional Court matters are determined; the Constitutional Court’s deference to the Executive; and the fact that there is no right of appeal from the decisions of the Constitutional Court. The objective was not just to win the matter but to do so in an effective, efficient and timely manner. And I was right because Chapter One Foundation has not stopped the Commission from creating a new voters’ register using the strategy it adopted and the court it approached.

The board: “He further asserts that, as the more “junior” lawyers to the lawyers in the other cases, the lawyers on the Chapter One Foundation case should have yielded to the other lawyers’ position. As lawyers can attest, there are many ways of approaching a legal case that take into account various considerations, some of which we have discussed.”

Comment: The law is not only for lawyers. Ignorance of the law, as the board and Kasonde know, is no defence. I am not a lawyer but a citizen, and this identity places on me the duty and burden to know, follow, defend and obey Zambian laws and the Constitution, whether I am qualified and practising law or not. Every lawyer must know this. In the matter of the amendment that Kasonde made to her petition before the Constitutional Court which was then used by the High Court to stall related proceedings before it, the board and Chapter One Foundation should have seen the wisdom and combined experience of the well-meaning people who asked them to withdraw the amendment. Among these were senior lawyers. Alternatively, the board should explain why Kasonde and the Foundation did not remove the amendment. The burden is on them to explain why the combined wisdom and experience of ‘senior’ lawyers was inferior to the position they took which has landed us where we are.

The board: “Having weighed our options, we decided to file a petition in the Constitutional Court taking a broad approach to defend and protect the constitutional right to vote.”

Comment: The seriousness and urgent nature of the case did not provide for ‘broad’ approaches. It simply required an effective approach that would have stopped the immediate implementation of an administrative action from the ECZ: the discarding of the existing voters’ register and the manufacturing of a new one that would possibly favour the incumbent. That is what was at stake.

The board: “Also, this year marks Ms. Kasonde’s twentieth year of practice, she is hardly a novice.”

Comment: I am surprised at this uncharitable response. My reference was to “experience” not longevity – someone with two years period of practice may have more “experience” than a qualified person holding on to their qualifications for 40 years but never “practised” their trade in specific branches of the law. This was the sense in which l compared the lawyers. I was not questioning her longevity, but her exhibition of poor judgement on a very specific issue.

I hold Linda Kasonde in high esteem. Whatever I have written does not diminish my personal respect for her as a practising lawyer and civil rights campaigner. Even in my Class of Zambians who inspired public trust in 2019, I praised her for creating Chapter One Foundation and using the body to oppose the Constitution of Zambia (Amendment) Bill Number 10 of 2019. But as the Bembas say, ubulimi bwakale tabutalalika umwana – one cannot rely on past glory to solve current problems. Similarly, Kasonde’s inspiring conduct does not confer on her any immunity from future criticism of her subsequent actions.

My argument was that unlike in 2019 when her actions inspired public trust, she betrayed Zambians in 2020 when she unintentionally aided in a plot to circumvent the electoral process and create a possibly dodgy voters’ roll. Her performance in 2020, specifically on the amendment issue under discussion and the gravity of it all, earned her a spot among Zambians who disappointed last year. It would therefore have been improper and unfair for me to deny her that accolade. Nothing that I said was meant to diminish my estimation of Kasonde’s professionalism, qualifications and the work that she has previously done and is currently doing for Zambia. As a matter of fact, I still hold her in high esteem.

The point is that I was dealing with a professional and serious national matter of greater public interest that is above my personal interests or what I think about her as a person more generally. Based on a very specific incident of last year, I termed Kasonde rigid, with poor judgement and in this instance an uncooperative attitude. Anyone could disagree with this assessment, but it is hard to see how it constitutes a brutal or destructive attack. Given the board’s admission that they were part of the poor decision making that inspired the amendment action, Kasonde would do well to take a long hard look at herself, internalise the criticism that she has received from many other well-meaning people on this episode and learn from it.

The board again: “But that notwithstanding, at Chapter One Foundation we do not believe that junior lawyers have nothing to offer. Our team is made up of highly competent young lawyers whose advice we rely on.”

Comment: Here, the board is doing some form of image building for its executive director and wants to turn young lawyers against me. I am aware that there has been a good and progressive movement to campaign for young lawyers who cannot find work. I know the acuteness of the state of joblessness among young lawyers, many of whom are very talented. I take my hat off to the young people Kasonde has gathered around her and appreciate the fact that she is doing her bit to develop and bring up some of them. But this was not the issue. What was at stake was that the October amendment, generated by Kasonde and her young lawyers, frustrated the efforts of others to stop the ECZ from effectively disfranchising registered voters. Would they rise to the occasion and acknowledge that they failed at this task? Competence includes having the judgement to acknowledge one’s mistakes and failures.

The board: “The one sidedness of his arguments.In his article, Dr. Sishuwa questions the decisions taken by Chapter One Foundation on technical grounds without having engaged Chapter One Foundation on the issue.”

Comment: In the public domain, I have every right to deal with the effects of any organisation that operates in it. I accept the view that the board of Chapter One Foundation might have their own explanations for what they did, but the truth is that they have failed to stop what they sought to prevent. What is at fault is the wisdom, strategy and legal and technical grounds that informed their actions. Everything that went into producing those decisions needs to be evaluated, which is why I have accepted meeting them so that they may educate me on how they arrived at making those decisions and actions. Needless to say, just because I am not a lawyer does not mean that my argument should be dismissed. If a child tells an adult that they are lying, the task of the adult is not to dismiss what has been said based on the idea that the child is not culturally and morally qualified to pass that verdict. It is to go beyond the cultural sensibilities to convince the child that what they (the adult person) are saying is true.

The board again: “He however does not seem to question the decisions taken by the other litigants.”

Comment: On the decisive and specific issue of how Kasonde’s amendment in the Constitutional Court led to the indefinite postponement of proceedings before the High Court, what am I supposed to question about the other litigants? Is the board disputing the argument that their executive director offered the High Court a lifeline? In this instance, I agree with the others that going to the High Court offered the most effective way of stopping the planned action of ECZ. It did not matter who went to court to ask that the process be stopped. The issue here is that Kasonde amended her cause in the Constitutional Court which amendment enabled the High Court to stall proceedings until her matter was determined. That is what is at stake.

The board: “We look forward to engaging with Dr. Sishuwa to provide our viewpoint on these matters as we believe in constructive debate on issues, particularly issues of national importance.”

Comment: I appreciate this sentiment from the board members of the civic body. I truly look forward to meeting all of them and having an informed conversation on these issues. As previously stated, I am ready to meet them and am looking forward to receiving the invite at the venue of their choosing, given the pandemic.

The board: “Chapter One Foundation expects and indeed welcomes fair criticism of our actions. We do not believe that anyone has a monopoly on knowledge. Our small team works very hard to promote human rights, constitutionalism, and the rule of law in Zambia to the best of our ability.”

Comment: This is a slogan. It is not my wish to interfere with other people’s slogans. Many are not what they claim to be. What is at issue is how the board and Kasonde, through their infamous amendment, enabled the High Court to not give the decision that would have stopped ECZ from disfranchising many Zambians.

3 responses

Iyo kwena. Chapter One Foundation should really think this one through objectively. Because Sishuwa is merely holding a mirror for them and they clearly didn’t like what they saw! What a grave mistake, of which we have not even begun to experience the true consequences of it all. I now understand why EL is confident of winning. He has the new register that is favourable to him, certified by chapter one foundation.

Thanks dedication to interrogate learned behaviour is inspirational,never at anytime in our lives assume that humans will behave the same way as programmed robots,all what someone need to do when presented with truth(new light) is to seek for a remedy so that character is preserved.