On 17 January 2025, President Hakainde Hichilema appointed a new five-member board of the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) to replace the Musa Mwenye-led ACC board that he dissolved in panic after one of his presidential aides is said to have informed him that the anti-graft body was preparing to arrest Solicitor General Marshal Muchende. Those appointed include retired Supreme Court judge Evans Hamaundu, who succeeds Mwenye as chairperson, legal practitioner Kaumbu Mwondela, former diplomat Jack Kalala, and governance activists Engwase Mwale and Nalucha Ziba. Hichilema also appointed Daphne Chabu, a member of the ruling United Party for National Development (UPND), as ACC director general.

Commenting on these appointments, former ACC board member and University of Zambia (UNZA) constitutional law lecturer O’Brien Kaaba praised the new ACC board for its “collective courage to accept to serve on the ACC board”, despite the likelihood that they will “be scrutinised and insulted for nothing in return.” The University of South Africa (UNISA) graduate continued: “During my term there [on the ACC board], for example, Sishuwa Sishuwa wrote about three articles claiming that the government had bought us [i.e. the ACC board] into silence”, Kaaba wrote. The former ACC board member assured the Hamaundu-led board of presidential support, describing Hichilema as someone who “is committed to letting no one in his government to escape accountability”. All that the new team would need to do, Kaaba explained, is simply “actualise that [presidential commitment] and ensure [that] no one is spared”.

There are three fundamental points I wish to make on this subject.

The first is that I have never written a single article, let alone three articles, in which I “scrutinised” or “insulted” the Mwenye-led ACC board or stated that the government had bought the board into silence. I have the highest regard for Musa Mwenye and consider him one of Zambia’s most forthright and upstanding citizens. I respected his leadership of the board notwithstanding the significant constraints within which he and his team operated. Not once did I say that the government had bought the Mwenye-led ACC board into silence. All my political commentaries are in the public domain, and their review would yield no evidence in support of any assertions to the contrary. Like anybody else, Kaaba is welcome to criticise my commentaries on Zambia’s political affairs, but his decision to spread falsehoods is regrettable.

The only substantive criticism I have ever made about Kaaba’s actions – criticism that had absolutely nothing to do with the ACC board – was his decision to cut a questionable deal with Solicitor General Marshal Muchende days after telling the public that Muchende was corrupt and that he had sufficient evidence to prove his assertion in the courts of law. It is worth recalling that Kaaba was the sued party in the matter and had no reason whatsoever to cooperate with the Solicitor General, who had two clear options: either discontinue the case on his own or continue with it so that he could prove his innocence. After Kaaba wilfully entered into a consent judgement with Solicitor General Muchende, whom he had publicly branded corrupt, I felt that the UNZA law lecturer had not only betrayed public trust but also demonstrated a disturbing lack of loyalty to principle. If Kaaba is truly an anti-corruption activist, I asked myself, why did he not allow the case to proceed to trial so that the public is afforded the opportunity to know the truth about the alleged corruption of Solicitor General Muchende who, because of Kaaba’s actions, remains in his position to date?

A principled person and defender of public interest should never be intimidated by anyone, particularly if they are certain of what they have stated. Such a principled person should, especially if an intellectual, be willing to bring out the truth irrespective of the consequences that may come their way. They should be prepared to defend the justness and veracity of their convictions even in the face of death. By entering into a shady deal with Solicitor General Muchende without any rational explanation of how the public interest was advanced through it, Kaaba lost, in my opinion, the right to be taken seriously when he talks about corruption. If Kaaba is trying to launder or cleanse himself of his questionable consent judgement with Solicitor General Muchende, he should do so without trying to cast aspersions on my reputation – as understandable as his penchant for doing so is.

The second and more serious point to be made about the new ACC leadership is that their appointment demonstrates Hichilema’s continued lack of serious commitment and political will to fight corruption. Any effective or serious fight against corruption requires, in my view, three crucial elements.

The first element is supportive or empowering legislation. There will be no serious fight against corruption in Zambia if the law that establishes the ACC is not amended to address its longstanding weaknesses. As currently structured, the Anti-Corruption Act is not equipped to fight corruption. In fact, I would go as far as saying that the Act is so flawed that one must be out of one’s mind to accept an appointment to the board because there is nothing serious that they are going to do. The Act currently provides for the board and the director general to be appointed by the President. This is an anomaly since it makes those in the ACC management feel answerable to the President, not the board. This limitation helps explain why former ACC director general Gilbert Phiri and his successor Thom Shamakamba showed contempt for the very board on which Kaaba served because they knew that there was nothing that the board could do to them, even if they failed to discharge their responsibilities. This should not happen. The ACC should be an independent body that must not be under the supervision of the President – himself a prime candidate for high-level corruption.

What is needed is to empower the board to choose the director general and the deputy so that the management officials are answerable to the appointing authority: the board. The board itself should be made answerable to the National Assembly, not to the President. This can only be possible with amendments to the existing law. As it stands, the ACC board has no control over the ACC management. The board can neither discipline nor fire those in the executive leadership. If Hichilema was as committed to fighting corruption as Kaaba would want us to believe, the President would have first changed the law to address these structural inadequacies that undermine the work of the board, including the one on which Kaaba served, before appointing a new board. After all, such a change requires a simple majority in the National Assembly and can easily be passed by ruling party MPs alone. After three years in office, and with a clear majority in parliament, what excuse does President Hichilema have for his failure to enact the necessary changes to the anti-corruption law?

Any President of Zambia who is seriously committed to fighting corruption, rather than merely paying lip service to it, would also have no problem amending the law to increase the sentences for those convicted of corruption. Currently, the law provides for very short sentences for corruption offences, generally ranging from two to five years. The net effect of this lack of stiffer punishments is that potential offenders feel emboldened to engage in acts of corruption since they know that even if they are convicted and sent to jail, it would not be long before they are out to enjoy the loot, stolen from poor Zambians. Again, if Hichilema had the will to fight corruption as Kaaba would want us to believe, the President would have changed the law to ensure that corruption offences attract a life sentence or a minimum of at least twenty years in prison. Since Zambia’s experience shows that most of those who engage in high-level corruption are members of the executive, we may understand the reluctance by Hichilema to enact stiffer penalties for corruption as entirely self-serving or deliberate.

The second element of a successful strategy of fighting corruption is the presence in anti-corruption bodies of men and women with proven integrity. Individuals who are appointed to the ACC board and management positions should be professionals with a clear track record of fighting corruption. This explains why the appointment of Mwenye as ACC board chairperson was met with widespread approval, given his distinguished record of opposition to corruption. In fact, what successive Zambian presidents have done is to appoint pliable executive heads of the ACC and seemingly strong-minded individual board members who cannot effectively supervise the pliable heads due to the structural constraints I cited earlier. This is the strategy that Hichilema has now perfected. In appointing highly regarded professionals like Mwenye to the ACC board, Hichilema’s objective was never to fight corruption – noticeable evidence suggests that the President retains an extraordinary fear for competent and independent-minded people and has a penchant for surrounding himself with Yes Persons – but rather to hoodwink Western actors into believing that he is committed to fighting corruption by hoisting a strong board that is however rendered ineffective by legal constraints and a pliant ACC executive leadership.

This strategy might explain why Hichilema, even this time, has appointed a ruling party loyalist as ACC director general whilst giving a veneer of seriousness to the anti-graft campaign by appointing individuals with generally respectable characters like Nalucha and Mwale as board members. Until her appointment, Chabu was Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Lands. Successive surveys by Transparency International Zambia (TIZ) have shown that the most corrupt ministries in Zambia are health and lands. How does anyone who is serious about fighting corruption appoint a controlling officer from one of the country’s most corrupt ministries – and potentially a corruption suspect herself– to head an anti-corruption body? Given her well known political ties to both Hichilema and the ruling party, can the new ACC director general be expected to prosecute her fellow party members including ministers involved in corruption? Simply put, what anti-corruption credentials does Chabu have that made her a suitable choice for the role she has been assigned?

What is needed for a successful anti-corruption fight, in addition to structural reforms, is having non-partisan individuals with a proven commitment to anti-corruption and moral wealth of character in both the board and the executive roles of the ACC. The best way of finding or recruiting such talent is through an open and transparent system of appointment where vacancies on the ACC board or management are advertised and interested people are invited to apply. This way, only the most qualified, competent professionals and individuals known to be committed to the fight against corruption will be hired into the Commission. For this to happen, the government needs to first create a merit-based system that would provide for formal qualifications and requisite qualities that interested candidates must possess. This approach would allow anti-corruption bodies to fill existing vacancies only after a thorough interview and public vetting process in which the presidency is hardly involved. It is one that I have consistently advocated, even when it comes to other public roles such as judges.

Again, if Hichilema had the will and commitment to fighting corruption as Kaaba would want us to believe, the President would have first established such a system, as opposed to maintaining the status quo and packing the ACC with his loyalists. As it stands, it is difficult to know what non-subjective criteria is used to identify the ACC board members and management leaders for appointment. Where, for instance, is the evidence that the individual members appointed by Hichilema have, both in their personal and professional lives, the DNA that is required to fight corruption? If Hichilema was serious about it, he would have considered creating merit-based systems that would ensure that those who end up in bodies such as the ACC represent the best talent available for the roles. There is surely no shortage of competent, impartial, and professional Zambians who can serve both on the ACC board and in the executive.

As it stands, any person who agrees to serve on the ACC board, as currently constituted by law and despite their knowledge of the challenges that the Mwenye-led board encountered, is potentially corrupt. This is because they are, in effect, accepting to be drawing public funds in form of allowances for doing nothing meaningful. I know that Kaaba said board members get very little money, but the principal issue is the principle, not the amount. How does any self-respecting professional accept an appointment to a role where they know – ignorance is an even more serious defect – that they cannot make any meaningful change because of structural limitations? What exactly are they going to do? The point is that even if the ACC board and management positions are filled with professionals of proven integrity, they cannot do much about the fight against corruption if the law remains unchanged. In fact, anyone who is seriously committed to fighting corruption will first check the enabling law and, once they realise that the law sets them up to fail, respectfully decline the appointment.

The third element of a successful anti-corruption campaign is having a President who shows a clear or demonstrable will to fight past and especially present corruption. Such political will can be demonstrated in several ways. One is to strengthen anti-corruption laws. Two is to deal decisively with the corruption of their officials or associates including those in the inner circle. The other is leading by example. A brief review of Hichilema’s record over the last three years shows remarkable failure on all three examples. The President has not initiated any meaningful changes to the Anti-Corruption Act. Neither has he sought to align the Act with Article 216 of Zambia’s constitution that provides for the guiding principles relating to commissions:

“A commission shall —

(a) be subject only to this Constitution and the law;

(b) be independent and not be subject to the control of a person or an authority in the performance of its functions;

(c) act with dignity, professionalism, propriety and integrity;

(d) be non-partisan; and

(e) be impartial in the exercise of its authority.”

Since the Anti-Corruption Act was enacted before the 2016 constitutional amendment, it should have been amended to bring it in line with these constitutional principles. Hichilema has failed to preside over such changes while some of the officials he has appointed to executive roles in the ACC have, in subordinating themselves to his authority and acting in a manner that conveys partisanship or partiality, shown a clear lack of respect for these constitutional principles.

Furthermore, Hichilema has failed to lead the ant-corruption fight using personal example. The President, who boasts of extensive business interests in several sectors of Zambia’s economy, has refused to publicly declare his assets and liabilities as a show of his commitment to transparency and accountability. This makes it difficult to work out to what extent his policies are benefiting companies in which he has an interest. Hichilema and his supporters like arguing that there is no law that requires him to publish their declarations, but as US ambassador to Zambia Michael Gonzales correctly noted recently, “leadership is not about only doing the bare minimum that is absolutely required by law, but going beyond and doing what is right and needed to lead and shape reforms.” In any case, if Hichilema truly has the political will to fight corruption, and after three years in office, what exactly has stopped his administration from passing a law that would make assets declaration and publication – both for his office and other senior government officials – an annual requirement?

Hichilema has also shown an incriminating reluctance to dismiss ministers and other senior government officials accused of involvement in corruption. There are several credible reports of ministers and other public officials who engage in vote buying or use government resources to campaign for the ruling party in parliamentary or ward level by-elections. These include reports from civil society organisations such as TIZ and the Christian Churches Monitoring Group. None of the errant senior officials serving in Hichilema’s administration have to date been dismissed from their roles or prosecuted for this blatant abuse of authority of office – an offence under the Anti-Corruption Act. As Gonzales argued, “There must be consequences for individuals who abuse their public positions for personal gain. They must lose their jobs, their assets, and/or their freedom. The costs of corruption must exceed the financial gain if we are going to stem corrupt practices.”

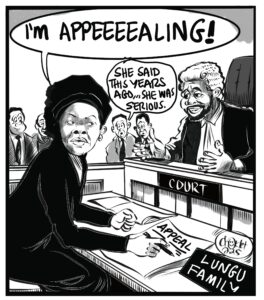

Given this abbreviated history of Hichilema’s cavalier attitude to the fight against corruption, I am at pains to understand why Kaaba would present such a record of failure as evidence that “Hichilema is committed to letting no one in his government to escape accountability”. If there is anything that Hichilema has done, it is to throw away any pretension that he is serious about the fight against corruption. I just wish the President could go a step further and change the name of the Anti-Corruption Commission to the more appropriate Pro-Corruption Commission (PCC).

The third and final point to be made about the new appointments to the ACC leadership relates to Hichilema’s continuing failure to reflect adequate ethnic diversity in his public appointments. What is with Hichilema and his clear preference for Zambians who hail from Southern, Western, and Northwestern provinces and/or the auxiliary ethnic language groups? It is as if a general prerequisite for appointment to investigative wings or law enforcement agencies under Hichiema is that one must hail from these provinces, collectively known as the Zambezi region, or at least have a biological parent who does. Director of Public Prosecutions Gilbert Phiri and another head of a separate law enforcement agency are prime examples on this score, since at least one of their biological parents is an ethnic Tonga. Out of the six latest appointments that Hichilema has made to the ACC leadership, at least five of them hail from the Zambezi region and/or the auxiliary ethnic language groups. Having an anti-corruption body that is dominated by Zambians from one region may justifiably give room to perceptions of persecution from the marginalised ethnic-language groups. In any case, wasn’t this kind of regional bias or lack of adequate diversity in public appointments the same thing that Hichilema criticised when he was in opposition?

I repeat: Hichilema lacks serious or demonstrable political will to fight corruption. His strategy on this subject appears to be covering his tracks and hiding corruption. The President knows voters despise graft – a key reason they ejected his predecessor – and he is determined to prevent not so much corruption itself but the perception of it under his administration or among his senior officials. Mwenye’s board, as Kaaba has said, attempted to fight corruption in Hichilema’s administration, but ended up humiliatingly booted out by the very President who, according to the UNZA law lecturer, “is committed to letting no one in his government to escape accountability”. What exactly is the UNISA graduate trying to communicate about Hichilema and the new ACC board? Given the President’s poor record on fighting corruption in his government, why is Kaaba laundering Hichilema’s bogus fight against corruption?

2 responses

Sishuwa – that’s so shallow to go as far as mentioning where one graduate…, what are you insinuating? Clearly, you want to contrast with you time at Oxford.., and guess what, it matters less where one qualified. No wonder everyone calls themselves Dr. Bla.., it’s mindset of characters like that think academic grades and or name value of a learning institution is correlated to relevance after school.