In last week’s Monday Opinion, I focused on elucidating how we can harness the economic potential of Zambia’s mining sector through the lens of local content and Artisanal and Small-scale Mining (ASM). Particularly, I dissected the challenges within the sector on these two fronts. In today’s Monday Opinion, I take the discussion further to prescribe solutions to these challenges.

(i) Local Content Strategy

Resolving Zambia’s local content challenges will require a thorough analysis of the local context. There is a need to identify intervention points in the mine project life cycle and create linkages between mining firms and local suppliers. This will aid in reducing the gap between supplier capabilities and demands by mining firms. To effectively build these linkages, it is cardinal that domestic firms supply goods and services on time and of reasonable quality. This can only come to fruition by developing a competitive local manufacturing and supply base. This partially entails the government creating incentives that support local contractors and suppliers. Secondly, it is cardinal that local content requirements reflect the realism of local supplier capability and demand of industrial assets by mining firms. Penultimately, those in leadership need to be selfless in instituting policies that benefit local suppliers and contractors. Lastly, there is a need for Zambia’s mining local content framework to focus on dynamic elements which aim to improve supplier capabilities rather than a narrowed static approach that merely focuses on employing and developing local manpower.

(ii) Artisanal and Small-scale Mining

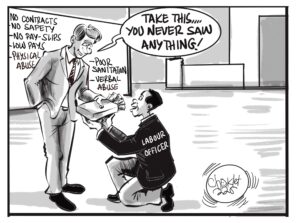

As highlighted in last week’s Monday Opinion the ASM sector faces several challenges including lack of capital, poor occupational health and safety, poor mine planning practices, presence of illegal miners, high fiscal rates, inefficient use of mining and processing techniques, lack of an easily available lucrative market, lack of geological information, etc. These challenges affect the industrialization potential of ASM and its real contribution to the Zambian economy. It is also important to appreciate the fact that there are interdependencies among these challenges. For instance, lack of capital and geological information has a transmission effect to cause other challenges such as poor mine planning practices, and the use of inefficient mining technology.

This subsequently leads to poor occupational health and safety conditions at mine sites. Similarly, high fiscal rates fuel illegality because informal miners will shy away from stepping into the formal space in fear of their hard-earned production being taxed. In formulating strategies to address these challenges it is cardinal that government comprehends their interdependent nature. In other words, the government must direct its energies in resolving causal rather than effect challenges. In dichotomising problems of the ASM sub-sectors, three causal challenges always emanate as being critical, namely, lack of geological information, lack of capital, and high fiscal rates.

Despite its important technical and economic function, the provision of geological information to ASM operators has always been problematic because the Geological Survey Department (GSD) under the Ministry of Mines and Minerals Development (MMMD) is poorly resourced and underfunded thus undermining its capability to discharge its functions.

This can be attributed to the fact that the Government has a limited operational budget to support the mining sector because resources need to be directed to other public expenditures. To partially resolve this challenge government can apportion a percentage of mineral royalty collected from the ASM sector to provide geological information. This fiscal instrument is suitable because it is paid by mining companies for the exhaustion of the mineral resource. Therefore, it is logical and rational to use it in replenishing exhausted deposits by searching for new ones. Secondly, lack of capital to exploit orebodies has been problematic for artisans and small-scale miners. This can be attributed to two primary reasons. Firstly, ASM operators are considered to be very risky debtors by financiers because they lack the collateral and bankable feasibility study reports.

This situation is exacerbated by a lack of geological information on their part. Therefore, the bankability of most artisan and small-scale projects cannot be ascertained in the absence of these reports. Even when finance is eventually sourced it is very expensive. Therefore, government needs to facilitate easy access to cheap finance. If government decides to provide this finance through dispensing equipment, it needs to ensure that this is a function of the amount of mineral reserves. This is because it is illogical to provide equipment to artisans and small-scale miners with limited reserve potential in their mining areas. Lastly, high fiscal rates can be remedied by crafting a sector-specific fiscal regime for the ASM sector which is reflective of their cost, revenue, and profit profiles.

To ensure the ASM sector is efficiently and effectively managed a separate unit should be created within the MMMD to manage its affairs. This unit must work in close collaboration with the Ministry of small and medium enterprises development.

This is it for this week. Look out for next week’s article as we discuss another exciting topic.

About the Author

Webby Banda is a Senior Researcher (Extractives) at The Centre for Trade Policy and Development (CTPD) and a Lecturer with the University of Zambia, School of Mines.