Since 2022, Zambia has made significant steps towards consolidating democracy through law reforms. The decades-long debate about the constitutional legitimacy of the crime of defamation of the President was resolved by the National Assembly through the amendment of the Penal Code, Chapter 87 of the Laws of Zambia, and the Criminal Procedure Code, Chapter 88 of the Laws of Zambia. These amendments also abolished the death penalty for civilians; those in the defence forces are still liable to receiving the death penalty for capital offences.

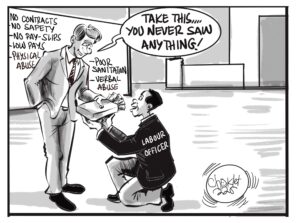

Despite these notable legal reforms, the struggle against draconian laws is unfortunately not yet over. As the jubilation continues, over the scrapping of the offence of defamation of the President, opposition political parties, civil society, activists, and citizens should understand that the offence of criminal defamation still exists and could potentially be used by successive governments to curb dissent, even against the Republican President. Section 191 of the Penal Code, Chapter 87 of the Laws of Zambia still criminalises the publication of any defamatory matter concerning another person with the intention of defaming that other person and it covers any defamatory matter published by print, writing, painting, effigy, or by any means otherwise than solely by gestures, spoken words, or other sounds. Any person who is found guilty of this misdemeanour is liable to serve a sentence of up to 2 years in prison or a fine or both.

Defamation generally is concerned with the protection of reputations of other persons even as one enjoys their freedom of expression. Criminalising free expression is not justifiable in a constitutional democracy. I It creates an atmosphere of self-censorship among journalists, the media and general citizenry. This is more dangerous for a society than actual censorship, which occurs on a case-by-case basis, as opposed to self-censorship which operates like a dark cloud of fear on all citizens and constrains their ability to express themselves.

This position is fortified by resolution 168 of the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights, at its meeting on 24 November 2010, in Banjul, Gambia, on its 48th Ordinary session. By this resolution, the Commission made it very clear that “Criminal defamation laws constitute a serious interference with freedom of expression and impede the role of the media as a watchdog, preventing journalists and media practitioners [from] practising their profession without fear and in good faith.” The African Commission on Human and People’s Rights further urged States Parties to “repeal criminal defamation laws or insult laws which impede freedom of speech, and to adhere to the provisions of freedom of expression, articulated in the African Charter, the Declaration, and other regional and international instruments”. Despite this resolution, African States, including Zambia, have actively kept insult laws and those relating to criminal defamation on their statute books, a position which continues to stifle free speech, press freedoms and globally accepted freedom of expression standards which Zambia has constitutionally guaranteed.

One may ask, how then does the law continue to protect the reputations of people who are defamed by the writings, print, effigy, paintings, or other expressions of those who claim to be championing freedom of expression? The answer is very simple – civil defamation proceedings. Through civil defamation, one will be able to prove that they have been defamed through the publication of a defamatory matter and their reputation has been lowered in the eyes of right-thinking members of society and therefore they seek an apology, retraction, and damages for the injury they have suffered. An opportunity would also be given to the other party to defend themselves with defences that are available to a defendant in a defamation action. The idea is that whereas we wish to protect the reputation of persons, there should not be arbitrary and restrictive provisions that completely water down freedom of expression though arrests, imprisonment, or self-censorship.

Zambian citizens should know that though the offence of defamation of the President is gone, criminal defamation is still enforceable law under our statute books. This is a reminder that there is need to work on its repeal. While it is in force, citizens must be careful to not find themselves on the wrong side of the law. A law can be arbitrary and undemocratic and at the same time enforceable, it is up to the citizens to join the call for its repeal, a position which is necessary for creation of a conducive environment for democracy and freedom of expression in our country.

Chapter One Foundation is a civil society organization that promotes and protects human rights, constitutionalism, the rule of law and social justice in Zambia. Please follow us on Facebook under the page ‘Chapter One Foundation’ and on Twitter and Instagram @CofZambia. You may also email us at [email protected]