Introduction

In 2018, the National Health Insurance Act was passed which saw the establishment of the National Health Insurance Management Authority (NHIMA)— a corporate body tasked with “implementing, operating and managing the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in Zambia”. NHIS was set up for the sole purpose of “providing universal access to quality insured health care services for Zambians”. NHIMA has, however, faced numerous challenges that have threatened its ability to deliver on this promise. In April 2024, NHIMA attempted to adjust the benefits package which included the removal of 24 benefits but reversed the decision. The Minister of Health also accused the private sector, alleging that they had contributed to NHIMA’s financial problems. NHIMA has also reported that it is paying service providers more than total monthly contributions. This article looks into the underlying causes of NHIMA’s struggles.

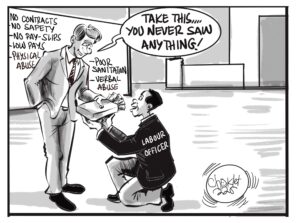

1. Inadequate Regulation and Opportunism by Private Providers

When the NHIS was initially rolled out, it was tested on government health care providers. Recognising that the government alone would not be able to meet the health care needs of its people, accreditation was extended to private health care providers (HCPs). However, this hybrid model of government and private health care accreditation has two fundamental requirements for its sustainability: absolute compliance and cost reflective claims by HCPs. While government HCPs have a little incentive to inflate claims, private HCPs often view NHIS as an opportunity to maximise earnings at the scheme’s expense. Unfortunately, this practice has continued for several reasons; there is currently no mechanism to verify and match claims against actual services provided. The issue is compounded by allegations that private HCPs do not show the bill to the patients after consultation and treatment. Thus, claims have exploited weaknesses in the system, leading to abuse and financial losses for NHIMA thereby undermining the scheme’s sustainability and efficacy.

2. Premature Rollout of NHIS

Before the rollout of NHIS, private HCPs were concerned about service costs and NHIMA’s ability to cover them. They also doubted the efficiency of government payments. Within just three years of NHIS’s launch, the total number of HCP rose to 219 of which 80 were private providers with over 100 pending applications. By May 2024, a total of 423 health care providers had been accredited, of which over half are private, reflecting increased interest from private HCP.

While subscribers to NHIS increased, it is the monthly claims that rose more sharply from just under 5,000 claims at inception to over 70,000 claims by end of 2021. Private HCP including dental hospitals and opticians saw an increase in delivery of services. Initially, patients could walk into an accredited optical facility, undergo an eye test, and obtain spectacles. This conflict of interest often led opticians to recommend lenses or services covered under the scheme. Although the requirement of independent hospital assessments eventually addressed this, it highlights how small loopholes can be exploited

3. Beneficiaries do not fully understand the scheme

A significant obstacle to the efficient operation of the NHIS is the widespread lack of understanding among beneficiaries regarding the scheme. While most beneficiaries understand basics such as the accredited HCPs and who can access them, there is a large gap in understanding other important aspects of the scheme such as the benefits package, the cost of services (which should ideally be given by HCPs but often is not) as well as approval process and timelines.

There have been reported cases where once a beneficiary logs in with an accredited HCP, they are pressured to continue with that provider and face difficulties if they wish to halt the process or switch to another provider. Some healthcare providers exploit this situation, making it difficult for beneficiaries to log out or change providers, thereby ensuring they can continue to make claims.

4. Insufficient Sensitization

Although NHIMA has been sharing “critical information” to the public through media and stakeholder engagements— under what it terms a “robust communication and stakeholder engagement plan”— it appears information on the role of beneficiaries in ensuring prudent financial management has not been part of NHIMA’s dissemination efforts.

Despite the visible root causes of NHIMA’s financial challenges, beneficiaries seemingly still do not understand fully that claims are drawn against their combined contributions with NHIMA. As such, they have a role to play in ensuring that these claims accurately reflect the services they receive.

Look out for part two next week, where I will delve into the reforms needed to save NHIMA.

About the Author

Ibrahim Kamara serves as the Head of Research at the Centre for Trade Policy and Development. He holds a bachelor’s degree in economics and finance as well as a master’s degree in public finance and taxation from the University of Lusaka. Ibrahim also served as the Coordinator for the Zambia Tax Platform until 2023.

2 responses

NHIMA should remove their services from the private hospital and clinics.

They should introduce a platform of Gold, platinum and silver for members