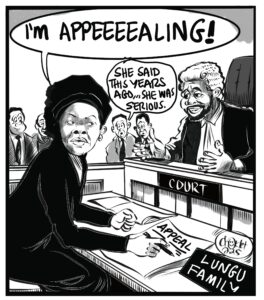

Last week, the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) arrested Minister of Infrastructure and Housing Development Ronald Kaoma Chitotela on suspicion of corruption. Chitotela, 46, was subsequently charged with two counts of concealing property suspected of being proceeds of crime, contrary to Section 71 (1) of the Forfeiture of Proceeds of Crime Act Number 19 of 2010. The minister was then released on police bond and is set to appear in court soon. Responding to public calls that Chitotela be removed from his ministerial position, President Edgar Lungu argued that he can only dismiss the Pambashe constituency Patriotic Front (PF) lawmaker if he is eventually found guilty. To avoid misrepresenting what Lungu said, it is worth quoting his remarks at length: “A suspect in the eyes of law enforcement agencies can be arrested. And they have chosen to arrest Honorable Chitotela…so they have to prove before the courts of law and I hope they give him a chance to prove himself, if he is corrupt…[To] those who are calling for the removal of Honorable Chitotela now, I say ‘no, give me space to breathe’, but don’t interfere with the process, bring your evidence but let him also have his day in court. That’s what justice [entails], and I am a lawyer. And if you look at the Bill of Rights, I think Article 18, it starts with presumption of innocence. So as far as I am concerned, he is innocent. I [have previously] lost Chishimba Kambwili because of allegations of corruption by the same forces. I don’t want to lose Chitotela in the same manner.”

I do not know which ‘same forces’ Lungu was referring to. What I know is that Lungu’s claim that his decision to keep Chitotela in his ministerial position has to do with his previously unknown commitment to the principles of natural justice is as unconvincing as it is laughable. Since when did one find Lungu and justice in the same sentence except when contrasting the two? Much has been said about the dismissal of former Minister of Community Development and Social Services Emerine Kabanshi as well as Zambia Postal Services Corporation Master General Macpherson Chanda to whom the principle of the presumption of ‘innocent until proven guilty’ was never applied before they were fired. Lungu has also been callously indifferent to thousands of civil servants who have been retired in his official name or in national interest, many of whom were never given a chance to be heard before they lost their jobs. In any case, both the Ministerial Code of Conduct and Section 47 (1) of the Anti-Corruption Act Number 3 of 2012 provide for the immediate suspension of those charged with corruption or facing criminal offenses in court. So what explains Lungu’s double standards in relation to Chitotela’s case? In my view, and broadly speaking, there are three reasons why Lungu is reluctant to drop Chitotela from Cabinet.

First, Lungu’s presidency has many centres of power, whose unifying and driving energy is accumulation, and Chitotela’s centre is one of them. The President fears that firing Chitotela might seriously disrupt the stability of the whole and potentially drive the Pambashe PF MP into the welcome arms of the opposition. Were he to be fired, there is no guarantee that a disappointed Chitotela might remain in the governing party; he may opt to join ranks with the fledging opposition Democratic Party, led by former Minister of Foreign Affairs Harry Kalaba, or even the main opposition United Party for National Development. Such a move, were it to materialise, is likely to embolden Lungu’s political opponents ahead of the likely-to-be-competitive 2021 election. The President’s reference to his ‘loss’ of Kambwili should be understood in this context.

When serving as a minister in government, Kambwili was not only one of the many centres of power but also Lungu’s most vociferous and fervent defender. There was no action the government and Lungu could take that he would not try to justify. Out of office, he has experienced a conversion like St Paul on the Road to Damascus. To diffuse any potential charge that he was previously close to the levers of power, Kambwili has quite successfully recast himself as the spokesperson for the ‘common man’, street vendors, university students, the workers and many others who are disillusioned with Lungu’s rule. In a context of what appears to be a systematic crackdown on free speech, he has also become one of the PF’s most trenchant public critics – exposing corruption in government, highlighting Lungu’s manifold inadequacies, denouncing economic exploitation by Chinese investors and refusing to be silenced. Although he is no Michael Sata, Kambwili is an effective grassroots mobiliser who has taken a significant portion of support away from the PF, which could potentially hurt the ruling party’s re-election prospects – especially on the Copperbelt where he is quite popular. This is the kind of political effect that Lungu fears may follow Chitotela’s dismissal from Cabinet and prosecution on corruption charges. Whereas Kabanshi was a political nonentity of little financial muscle, the President knows that Chitotela, who is part of a significant internal party faction dubbed ‘Luapula United’, may have amassed sufficient wealth to seriously mount an effective challenge to Lungu’s power outside the PF. Given his narrow election victory in 2016, his subsequent loss of Kambwili’s centre of power, and the impending social unrest that is likely to result from Zambia’s worsening economic situation, Lungu may have reasoned that he cannot afford to ‘lose’ Chitotela. Keeping him in his ministerial position thus prevents the arrested minister from leaving the PF to join Lungu’s opponents. A legal process conducted outside the ruling party could also provide Chitotela with a platform to launch criticisms of the government or accuse other key figures in the government including Lungu of corruption.

Second, Lungu may be reluctant to drop Chitotela from Cabinet probably because he thinks that the ACC has no power under the current legal dispensation to prosecute a serving Cabinet minister for corruption and abuse of office. Informed by this thinking, he may have reasoned, especially when the first point is taken into consideration, that the courts are thus likely to dismiss Chitotela’s case at its preliminary stage and, given this prospect, the benefit of keeping him in his ministerial post far exceeds the cost of dismissing him. Before demonstrating how flawed this thinking (reportedly espoused by the ACC itself) is, it is important to establish its roots. The view that the ACC presently has no powers to prosecute ministers is predicated on the idea that the earlier cited Anti-Corruption Act, under which the investigative body operates, only empowers it to initiate legal action against a ‘public officer’. The Act defines a public officer as ‘any person who is a member of, holds office in, is employed in the service of, or performs a function for, a public body, whether such membership, office, service, function or employment is permanent or temporary, appointed or elected, fulltime or part-time, or paid or unpaid’. The Act further defines a ‘public body’ as ‘the Government, any Ministry or department of the Government the National Assembly, the Judicature, a local authority, parastatal, board, council authority, commission or other body appointed by the Government, or established by, or under, any written law’. Zambia’s amended 2016 Constitution has however introduced another term, ‘state officer’, which is separate from ‘public officer’. Article 266 defines a public officer as ‘a person holding or acting in a public office but does not include a state officer, councillor, constitutional office holder, a judge and a judicial officer’. The clause further defines a ‘state officer’ as ‘a person holding or acting in state office’, itself defined as any office that ‘includes the office of the President, Vice-President, Speaker, Deputy Speaker, Member of Parliament, Minister and Provincial Minister’.

The ACC has read and understood these changed constitutional terminologies to mean that it no longer has any mandate to prosecute public officers who are now classified as State officers. It is this thinking that helps explain why the ACC charged Chitotela using the Penal Code and the Forfeiture of Proceeds of Crime Act, under which he can be prosecuted in his individual capacity, rather than the Anti-Corruption Act of 2012. It might also explain why the ACC may have decided against charging Chitotela with abuse of office for his other reported serious offences that emanate from the exercise of his official duties. I acknowledge the need to amend the relevant sections of the Anti-Corruption Act if only to formally bring the legislation into line with the changed provisions of the Constitution. However, I am not persuaded by the argument that the ACC cannot prosecute ministers as a result of Article 266, though the provision may have been specifically inserted into Zambia’s Constitution by the would-be plunderers based on the thinking that doing so would help cover them from prosecution. There is no law that expressly confers immunity from prosecution on Cabinet ministers. The only public official who enjoys such immunity is the President and even in his or her case, such immunity is not absolute. So, the ACC can still prosecute ministers for abuse of office, notwithstanding the definition of a public officer in the amended Constitution. I urge the ACC to bring more serious charges against Chitotela and any minister suspected of involvement in corruption.

I must confess though that I have little faith in the current ACC Acting Director-General Rosemary Khuzwayo and I am not the only one. I know many Zambians who also think she was put into the position because Lungu regarded her as a pliant individual who, like her counterpart in the office of the Director of Public Prosecutions Lillian Siyunyi, would be less likely to take the requirements of her job seriously, which in Khuzwayo’s case means proactively investigating corruption. Khuzwayo and her team should not use the terminologies of who is a public or state officer as the pretext on which they cannot prosecute perpetrators of corruption and those who abuse public office. They must enforce the law and, if in doubt about the meaning of who a public officer is in relation to the Anti-Corruption Act and the amended Constitution, should be the first to test the law and cause the courts to interpret it. Charging Chitotela or any minister with abuse of office would serve this purpose. Maintaining the status quo will only reinforce widespread public perceptions that Khuzwayo was put into her position to do the bidding of the executive arm of Government. I am aware that there are many forthright and upstanding junior officers in the ACC who are ready to go wherever the evidence leads them, but whose efforts are continuously thwarted by their superiors, who are more susceptible to political influence. If Khuzwayo does not enforce the law, she should prepare for the day when she will leave office and possibly face prosecution for perverting the course of justice.

The final and most probable reason why Chitotela is unlikely to lose his ministerial position is that his arrest is arguably a smokescreen designed to undermine growing public criticism of increased levels of corruption in Lungu’s administration. Opposition Patriots for Economic Progress (PeP) president Sean Tembo made reference to this point last week. Tembo is right. Hurt by the persistent criticism that he is presiding over a kleptocratic regime and eager to undermine such legitimate charges, Lungu may have sanctioned Chitotela’s arrest to intentionally mislead international donors and civil society organisations that he is committed to fighting corruption. Corruption has become so synonymous to Zambia under Lungu’s rule that outsiders’ knowledge of the country extends to little else. Previously, a Zambian could travel abroad in the knowledge that curious strangers would greet them with predictable remarks: ‘Oh, you are from Zambia, Kenneth Kaunda’s nation; or Kalusha Bwalya’s country’. Nowadays, the country is infamous for its commitment to corruption, especially in relation to public procurement, perpetrated by the basest of us – a coterie of unscrupulous elite scumbags, hypocrites, kakistocrats, and scoundrels of all sorts who somehow find themselves in power. The $42 million that the government allegedly spent on buying 42 fire trucks provides a trending example of how the country’s previously benign image has been replaced by a notorious one, characterised by the rampant official pillaging of public resources. The new image is one that even Zambia’s former vice-president Guy Scott could not escape from addressing in his recently released memoirs:

“The case of Zambia’s forty-two secondhand fire engines became known to everyone who has heard of Zambia – or at least cares about it. It seems so straightforward that it appeals to everyone, especially those who do not want to delve into more complex issues. In December 2015, Inonge Wina – now my successor as vice-president – reportedly announced that government had spent K40 million (perhaps $4 million, but it is hard to be exact as the Kwacha was wildly fluctuating at the time) on firefighting equipment, including forty-two fire engines. The whole issue then went quiet. Nearly two years later, fire engines were back in the news. Still forty-two of them, but by then costing $42 million. Even with spare tyres and smart new uniforms, there is simply no fire engine, new or secondhand, big or small, that costs $1 million.”

There are other cases, too numerous to mention, of grand official corruption that have occurred under Lungu’s watch. The point is that Lungu lacks any genuine commitment to fighting corruption. If anything, a predilection for corruption is generally seen by many Zambians as a prerequisite to winning Lungu’s favour or friendship. For some reason, Lungu generally repels the talented and attracts the violent, inept and most debased – those whose conduct betrays a lack of respect for themselves, for any moral and ethical values, the law and their appointing authority. This consideration probably explains why he re-appointed Chitotela – who, in December 2013, was dismissed from his ministerial position by then President Michael Sata for suspected corruption – to a ministerial post soon after his election in 2015. No sane Zambian can therefore accuse Lungu of retaining any hostility to graft. In more recent times, however, the tag of corruption has begun to really hurt both his and the PF’s image. It is one that they had hoped would fade away with time. Unfortunately for them, it has persisted and threatens to undermine the ruling party’s electoral prospects in 2021. Lungu’s lacklustre response to corruption has also seriously eroded public confidence in the credibility of state institutions such as the ACC, whose mandate is to fight the scourge.

In endorsing Chitotela’s arrest, Lungu is possibly seeking to hoodwink many into thinking that he is ‘a born again’, committed to fighting corruption and that State investigative agencies like the ACC retain the autonomy and support required for them to operate effectively. They can, if such institutions want, institute any charges against his ministers and he will not stand in their way. Khuzwayo and the ACC may also use this possibly staged stunt against Chitotela to project a modicum of independence and a false commitment to fighting corruption. Lungu and the ACC probably know, however, that all this is simply a façade. In the nearly impossible instance that Chitotela is convicted of corruption, Lungu can then use him as an example of his administration’s commitment to combatting the scourge. By that time, Chitotela would have become so disgraced that any party that welcomes him into its fold risks going down with him. Were he to be ultimately acquitted, Lungu, who has done much to undermine internal opposition to his rule, especially from those with wider political ambitions, would have succeeded in convincing Chitotela to see him as his paternalistic saviour who deserves sycophantic support.

For feedback, [email protected]; Twitter: @ssishuwa