Introduction

Last week, I explored critical issues undermining Zambia’s National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) and how they pose a threat to NHIMA’s financial and overall sustainability. I noted four fundamental issues which have contributed to the current financial struggles that NHIMA is experiencing— inadequate regulation, opportunism by private healthcare providers, premature rollout and poor beneficiary awareness have placed NHIMA in a precarious position. These gaps and weaknesses have jointly undermined the authority’s capacity such that NHIMA has publicly announced that it was making more monthly payments than receipts. This is bad enough. Any insurance scheme that does not get more revenue than claims drawn on it is bound to collapse. Therefore, urgent measures will need to be undertaken if NHIMA is to provide universal access to quality insured health care services for Zambians.

In this second part, I shift focus to the necessary reforms and policy measures that could save NHIMA from further deterioration.

1. Strengthening Regulatory Oversight and Claims Verification

Without dedicated oversight and claims verification, financial hemorrhage will continue to occur. NHIMA must do the following: Implement a robust digital verification platform for pre-approval requests to be submitted by health care providers on high-cost claims. While NHIMA has already pre-existing protocols on this—such as CT and MRI scans, there is room to expand this given that it is the frequency of other claims that in fact are problematic. Furthermore, an itemised billing, simplified to the extent that every beneficiary can understand and counter sign against before adoption as a legitimate claim should be mandated. This measure gives an opportunity for beneficiaries to report any discrepancies they observe. In addition, spot checks and audits should be conducted especially on private health care providers.

2. Financial Restructuring to Ensure NHIMA’s Long-Term Viability

NHIMA’s financing model is one that depends sorely on beneficiaries’ contributions pegged at a rate of 2 percent of the basic income for formal sector contributors and an average of 50 Kwacha (covering a family of up to 7 members) for those in the informal sector. NHIMA has acknowledged that this income stream is not adequate to sustain its operations and has called for an upwards adjustment. What needs to happen, however, is an assessment of the situation to ascertain what is required to sustain NHIMA based on current revenue and expenditure patterns. Furthermore, given governments position not to inject capital into the scheme, NHIMA may consider external partnerships with other institutions. However, Given Zambia’s regulatory framework and NHIMA’s role as the sole mandatory health insurer, a direct risk-sharing partnership with private insurers may not be immediately feasible. NHIMA can gradually integrate private insurers into the national health financing framework through a structured hybrid model.

3. Improving Public Awareness and Beneficiary Engagement

Raising awareness of beneficiaries through targeted sensitisation campaigns that educate them on their rights and responsibilities under NHIS is a necessary measure. It is only when beneficiaries are fully equipped with knowledge about the scheme, including financing and verification processes, that they can hold service care providers accountable and assist in making the scheme more transparent.

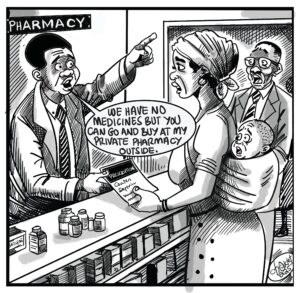

4. Revising NHIMA’s Accreditation Model for Private Providers

Given that private health care providers have been cited be opportunistic, NHIMA needs to reassess the criteria for accrediting private healthcare providers. This assessment must into account financial and ethical compliance as to reduce the risk of incorporating entities that are not compliant with NHIMA’s regulations. A performance-based system where accreditation is subject to continuous review based on service quality and compliance.

Preventing NHIMA’s Collapse

Financial distress is a common challenge facing most health insurance schemes. While a complete collapse of national health insurance schemes is uncommon, it is worth noting a few schemes around Africa that have experienced similar challenges. Ghana and Nigeria have both faced difficulties extending health care services to the poor due to financial and administrative inefficiencies. Kenya’s Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) also faced challenges albeit, due to inadequate infrastructure and consultation leading to a premature rollout. Tanzania’s National Health Insurance Fund is in dire need of an estimated $80 million owing to increased claims which it hopes government can settle. These cases underscore the practical challenges that health insurance schemes can experience if proper measures are not put in place.

Conclusion

NHIMA has not collapsed but it is evident that the current financial position is not sustainable. Making NHIMA resilient and viable in the long-term will require bold steps to effectively manage claims made by HCPs. While dealing with inflated claims will reduce the stress on NHIMA, it is the beneficiaries who also have an important role to play in ensuring the scheme is transparent and thus must be sensitized continuously.

About the Author

Ibrahim Kamara serves as the Head of Research at the Centre for Trade Policy and Development. He holds a bachelor’s degree in economics and finance as well as a master’s degree in public finance and taxation from the University of Lusaka. Ibrahim also served as the Coordinator for the Zambia Tax Platform until 2023.