On 8 November 2019, President Edgar Lungu, speaking in his first press conference for four years, brought up Zambia’s elections scheduled for 2021 before declaring: “I am game”.

Breaking with his usual practice of governing through press aides and off-the-cuff remarks delivered on airport tarmacs, he stressed publicly that he would be the presidential candidate for the ruling Patriotic Front (PF), in power since 2011, and would leave no stone unturned in his quest to secure a third term.

President Lungu was first elected in the 2015 presidential by-election that followed Michael Sata’s untimely death in office. He was then re-elected in the disputed 2016 polls, narrowly defeating Hakainde Hichilema, leader of the opposition United Party for National Development (UPND).

Since then, Zambia’s economy has faltered thanks to a combination of government incompetence, venality and external shocks. A devastating drought has left close to 2 million people in need of food aid and contributed to an electricity crisis that has seen power cuts for as long as 20 hours a day. Grand corruption has become so endemic one might be forgiven for mistaking it for an election promise on which the government has been striving to deliver. Meanwhile, policy uncertainty in the crucial mining industry has, together with low copper prices, slowed production. These factors have halved Zambia’s annual growth rate from nearly 4% in 2016 to just 2% in 2019, while external debt and inflation have surged.

These negative economic indicators have not only led to rising costs of living for ordinary Zambians, but also fed calls for political change within the ruling PF. Two broad factions have emerged in recent months.

Team Lungu

The first comprises party leaders supportive of President Lungu and his 2021 candidature. PF Secretary-General Davies Mwila has emerged as the most vociferous member of this group, while sources in the party say others in this faction include: presidential political adviser Kaizer Zulu; Health Minister Chitalu Chilufya; Minister of Home Affairs Stephen Kampyongo; Tourism Minister Ronald Chitotela; Minister of National Planning Alexander Chiteme; Lusaka Province Minister Bowman Lusambo; and various of Lungu’s business associates.

Among other things, those in this cohort are trying to show their loyalty to the president in the hope that if he does not stand, he will anoint one of them as his successor. Lungu is afraid of being prosecuted for corruption, embezzlement and criminal misuse of power if he leaves office. To protect himself, he might decide to remain in power for as long as possible or find a pliant replacement, the more loyal the better. Members of this faction also have deep vested interests in Lungu remaining as president. This is the surest way of guaranteeing their current positions of power and protecting themselves from prosecution.

Lungu’s attempt to secure a third term is therefore not just an individual aspiration. It is part of an elaborate plan by a whole PF faction that seeks to ride on his presumed popularity and control of the state apparatus to retain its positions of influence for the purposes of accumulation. One or two members of this group – such as Chilufya and Chitotela – are also rooting for Lungu in the hope that should he stand in 2021, he might nominate one of them as his running mate, a position that would give them great advantage in a future presidential bid.

The anti-Lungu brigade

The second faction consists of PF leaders who believe that fielding Lungu in the 2021 elections would be courting electoral defeat.

Although it lacks a clear leader, this group revolves around the figurehead of Kelvin Bwalya Fube, a former PF election deputy chairperson and charismatic lawyer who played an important role in securing Lungu’s nomination for the 2015 election. Fube has considerable appeal among disenchanted party youths, an influential constituency that was central to the dramatic fall of former PF Secretary-General Wynter Kabimba and the subsequent rise of both Mwila and Lungu following Sata’s death. Also backing Fube are some senior PF figures, including some cabinet ministers who fear reprisals if their support for him is revealed.

This group believes that Lungu is unpopular among the party’s rank-and-file as well as Zambians more generally. The massive turnout at public rallies of the main opposition leader Hichilema, even in supposedly PF strongholds such as the Copperbelt, has further raised concerns. This ruling party faction therefore wants a different presidential candidate for 2021.

The four-point plan to stop Lungu

PF Secretary-General Mwila has poured scorn on this possibility. Nonetheless, the group has designed a strategy to get rid of Lungu made up of four possible plans.

The first is to simply persuade Lungu to abandon his aspirations for 2021 and name a successor.

If this fails, the second is to turn to Zambia’s constitution, which now requires political parties to hold regular elections, to call on the PF Central Committee to hold an elective party convention. Sources in the party say plans are already underway to hold one in April 2020. At this convention, members of the Fube faction would sponsor a candidate to challenge Lungu for the 2021 nomination. Given Lungu’s lack of a firm grip on the PF, he might be vulnerable in such a race. This is why Lungu’s supporters are now lobbying the Central Committee to either ensure the incumbent is the only candidate or to cancel the need for a convention altogether.

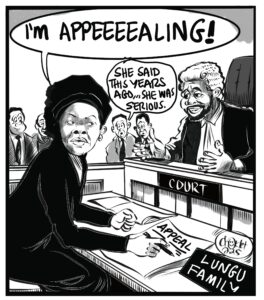

The third strategy is to use the courts to disqualify Lungu from running. Despite the president’s confidence, many people believe he is not legally eligible to run for another term as the constitution contains a clear two-term limit. The president’s supporters argue that his first term of just 18 months should not count towards this total, but Zambia’s Constitutional Court recently delivered an ambiguous ruling on this question, which has emboldened Lungu’s opponents.

Worried by the prospect of a legal challenge to Lungu’s nomination, the pro-Lungu faction has put forward a widely condemned constitutional amendment bill. Among other things, the bill would abolish constitutional provisions that currently allow any person to submit a legal contest to a candidate’s nomination.

The bill is set to be tabled for second reading at any time. To pass in Zambia’s 167-member National Assembly, it would require at least two-thirds support (at least 111 MPs). This is a tall order – especially if done through a secret ballot – given the PF’s narrow majority and questions over its MPs’ loyalty to Lungu. Aware of this uncertainty, its backers seem keen to postpone the process until it can be more confident of its outcome. The problem is that the more they delay, the more traction the anti-Lungu faction may gain.

Should all this fail, the Fube faction has a final fourth option: form a breakaway party, recruit many who have already been hounded out of the PF, and launch a political assault on Lungu as the opposition. Its aim would be to win power or, at the very least, make it impossible for Lungu to retain it.

Despite the PF’s disastrous management of the economy, it is fair to say that the internal factions in the ruling party are the real effective opposition in Zambia – that the PF’s greatest enemy is itself. One of the driving energies behind the ongoing rebellion against Lungu is the push for a Bemba-speaking candidate to succeed him. Although they harbour distinct presidential ambitions, PF leaders who are pro-Lungu, but hail from Bemba-speaking communities, and those outrightly opposed to him agree on one point: that his successor, be they from Team Lungu or the ant-Lungu brigade, must be a Bemba speaker.

The outcome of this raging power struggle for the leadership of Zambia’s governing party will have significant implications on its political standing and, depending on how the successful faction handles the political fallout and economic collapse, the potential for a transfer of power in 2021.

It is worth stressing that while the PF is saddled with deepening rifts, opposition parties appear to be holding together. They have continued to capitalise on the gradual implosion of the ruling party as well as the growing public revulsion to Lungu over his poor handling of the economy, the kleptocratic behaviour of his administration, the breakdown in the rule of law, and the shrinking democratic space.

2 responses

Dr. LUNGU THIRD TERM shall be heavily resisted by Zambian voters. Mr. SHALL be easy opponent to beat. Bishop JERICHO SIKWIILALA

I AGREE