‘Let’s just look at how this school is organized,’ said Mr Kafundisha, ‘and perhaps from that we can begin to build the picture of how the entire country is governed.’

‘Or misgoverned,’ came a voice from the back.

‘Fikansa,’ said Kafundisha sternly, ‘I hope you’re not going to follow your usual pattern of contradicting everything I say.’

‘And I hope you are not going to spoil your own lesson by constantly trying to stifle any discussion,’ replied Fikansa calmly.

‘The purpose of our lesson today,’ said Kafundisha, ‘is to discuss Chapter Ten on Our System of Government which you were asked to read for homework, so as to fully comprehend what it tells us about how our democracy works.’

‘Or doesn’t work,’ sneered Fikansa.

‘Taking the example of how this school is organized and governed, let us start off with an apparently simple little question: Who is in charge of this school?’

‘The headteacher,’ answered Bwalya.

‘Nonsense,’ declared Fikansa. ‘The poor old fellow can’t decide anything of any importance. He can’t even choose which teachers he wants for his school, they are just posted like parcels from the District Office.’

‘Fikansa,’ said Kafundisha, ‘you think I was posted here like a parcel?’

‘Yes,’ laughed Fikansa. ‘And when the day comes you will find yourself posted somewhere else, whether you like it or not.’

‘That’s enough, Fikansa,’ said Kafundisha sternly.

‘I only wish that were enough,’ retorted Fikansa. ‘But unfortunately that’s only the beginning of the sad story. The headteacher can’t control academic quality, since the Examinations Council sets the exams and decides what is academically acceptable. He cannot even decide what is taught, since that is decided by the same Curriculum Development Centre that wrote this silly chapter on Our System of Government.’

‘Oh, so now you know better than the Curriculum Development Centre! Tell me, Mr Clever Fikansa, what is wrong with this chapter on Our System of Government?’

‘It is entirely dishonest and misleading because it provides only an explanation of how government is supposed to work, but nothing at all about how government actually works.’

‘Can we have an example, please? We cannot conduct a discussion with empty generalities.’

‘Certainly,’ said Fikansa. ‘Only yesterday the secretary-general of the ruling party claimed that he is No.3 in the government and that all cabinet members are subordinate to him and accountable to him. But this book says cabinet ministers are accountable to parliament and doesn’t even mention any secretary-general.’

‘It seems to have escaped your attention, Fikansa, that to make this discussion more simple and understandable we are using the analogy of the governance of this school. In our chosen example, we would say that the headteacher is accountable to the Board of Governors and to the PTA.’

It seems to have escaped your attention,’ replied Fikansa, ‘that the headteacher is accountable only to the school caretaker, Mr Cadre Malonda, who happens to also be the party chairman for this District.’

‘Don’t be ridiculous, Fikansa. Mr Malonda may have a position in the party, but at this school he is just one of the support staff. The caretaker is responsible to the headteacher, and not the other way round.’

‘It seems to have escaped your attention,’ said Fikansa, ‘but Malonda has moved into the headteacher’s official residence on the school campus and has taken the headteacher’s eldest daughter as his third wife.’

‘That can’t be right,’ gasped Kafundisha, ‘that girl is only twelve years old.’

‘It seems to have escaped your attention,’ said Fikansa, ‘that child marriage is very prevalent, and Malonda is said to have paid K20,000 lobola.’

‘That can’t be true,’ scoffed Kafundisha, ‘you’re making this up as you go along. A caretaker is very lowly paid, and cannot possibly have afforded such a huge amount for lobola.’

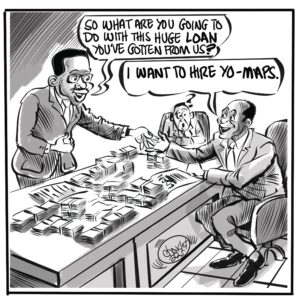

‘It seems to have escaped your attention,’ said Fikansa, ‘but Malonda used his party influence to get elected as treasurer of the PTA, and all the fees paid by parents are paid directly into his account. With his knowledge of the education system and his massive contributions to the party mobilization fund, he is strongly tipped to be appointed as the next permanent secretary in the Ministry of Education.’

‘Now you go too far. Perhaps there might have been a bit of slippage from good governance, but now you’re clearly just retailing some of the nonsense you read on social media. I’ve seen his file, and Mulonda is a Grade Four dropout.’

‘This may have escaped your attention,’ replied Fikansa, ‘but last year Malonda went on six weeks study leave, and returned with PhD degrees from both Oxford and Princeton. In fact he is now overqualified to be appointed a PS and may have to be made Minister of Education.’

‘He went to England and America and got two degrees in six weeks?’

‘It seems to have escaped your attention,’ said Fikansa, ‘but we have a University of Oxford in Chawama and a University of Princeton in Chimwemwe.’

‘Malonda is just a semi-educated bully,’ declared Kafundisha, ‘the president wouldn’t even appoint him as the Chief Bootlicker!’

‘It seems to have escaped your attention,’ said Fikansa, ‘that our beloved caretaker is standing right behind you.’

As Fikansa spoke, the burly Malonda grabbed the hapless skinny little Kafundisha and hurled him out through the classroom door, shouting ‘I’m transferring you to Chilubi Island for insulting the president!’