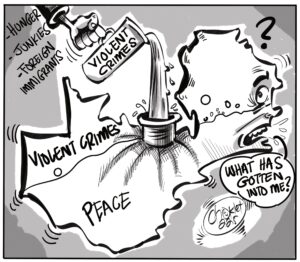

Zambians have been calling for an access to information law for about three decades. The intention behind these calls was to enable citizens to have greater access to information that is in the public interest to promote transparency and accountability in governance and in the conduct of public officials. However, the new Access to Information Bill not only doesn’t live up to expectations with regard to providing adequate transparency and accountability of public bodies; it also exposes private citizens like journalists, civil society actors, and even opposition political party members to potential surveillance by public authorities. Much like the story in Greek mythology, now that we have what we have been asking for, not only is not exactly what we were hoping for, but it also threatens to unleash misery upon the Zambian people.

In 2002, the Zambian government tabled the pre-cursor to the Access to Information Bill, which was called the Freedom of Information Bill, before Parliament. It was widely lauded as being a very progressive piece of legislation, however, it was never enacted. Over twenty years later, the UPND campaigned on a promise to deliver the Access to Information Act. The result is the current Access to Information Bill (ATI Bill) now tabled before the National Assembly. Whilst on the face of it, it appears to deliver what was promised, the Bill departs from the original Freedom of Information Bill of 2002 in significant ways which will be discussed subsequently. This begs the question, what was the mischief in the Freedom of Information Bill that the ATI Bill sought to remedy? It is important to mention that whilst the people of Zambia have been calling for the ATI Bill for three decades, what is even more important than having a law in place is having a good law in place.

One of the most significant departures in the ATI Bill is the lumping together of the obligations of public and private bodies whose obligations are not distinguished appropriately under the Bill. In the Bill the term “information holder”, the person responsible for providing the information, applies equally to public and private bodies. It is important to mention that one of the most important objectives of an ATI Bill is to allow citizens greater access to public information. The rational being that government and public officials must be open and transparent in their dealings to allow for greater accountability to the citizenry who either elect them to office or pay for their salaries using taxpayers’ money.

The failure to distinguish between public and private bodies provides onerous and even intrusive access to privately held information, whether individually or held by third parties. For example, the ATI Bill obliges private information holders to disclose certain information provided by third parties, which information can be disclosed with the “consent” of the third parties. This could potentially be very detrimental to privacy in a world where companies, such as mobile service providers, get subscribers to sign long contracts written in fine print. Many of these contracts purportedly give “consent” to the mobile service providers to deal with their personal data as they wish. This has potential repercussions for the surveillance of civil society activists, politicians, journalists, and even ordinary citizens.

Whilst there is a definition of what a “private body” is under the Bill, the Bill states that any such body that receives “public funds” and purports to act in the “public interest” is liable to disclose certain information. The problem lies in the fact that neither the term “public funds” or “public interest” have been defined in the Bill. So, for example, NGOs and even media houses could fall under this category again putting them under the risk of surveillance or intrusive scrutiny which was not the intention of those calling for the ATI Bill. We prefer the provisions of Section 10 of the original Freedom of Information Bill which clearly distinguishes between the obligations of public and private bodies and recognises that public bodies should be more accountable to the Zambian citizenry.

In addition, the ATI Bill states that “privileged information”, which includes lawyer-client privilege, doctor-patient privilege, and journalistic privilege that protects news sources, may be exempt from the provisions of the Bill under “any written law”. This term “written law” remains undefined. It is subsequently unclear as to whether the term “any written law” applies to court decisions on the issue of privilege, which more often than not has not been codified in a statute. The provisions of Section 3 of the old Freedom of Information Bill were preferable as they clearly outlined what constitutes privileged and confidential information and that such information was exempt from disclosure.

Also of concern is the fact that the Bill designates the Human Rights Commission as the “independent body” that will oversee appeals regarding refusal of information holders to disclose information. Firstly, the Commission is made up of presidential appointees which may call into question the independence of the institution. This falls short of international best practice on what an independent body is. Secondly, the job of the body that oversees access to information is very onerous, simply put, it’s a full-time job. Already the Human Rights Commission is understaffed and under resourced which begs the question – would be an effective oversight body? Thirdly, the Human Rights Commission is itself a public body receiving public funds from which the public may want to seek information. Who will police the Commission’s non-compliance with the ATI law? Equally worrying is the designation of the Ministry of Information to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the implementation of the ATI Bill. The Ministry of Information clearly is not an independent body and should not be seen to be interfering with how the Bill is implemented. We favour the provisions of Section 5 of the original Freedom of Information Bill which created a completely new purpose-built independent oversight body that is not made up of political appointees.

Regarding the sanctions for failure to disclose information, the ATI Bill provides for “administrative penalties”. As public offices are the most likely places where the public will be seeking information, these provisions call into question how effective these administrative penalties would be. For example, if a public official refuses to disclose information and is liable to a fine, that money will come from the taxpayers’ pockets. We favour the inclusion of personal responsibility of public officials who withhold, hide, or destroy information. This will be a more effective way of ensuring compliance with the law. Having said that, care needs to be taken to ensure that these public officials are not shielded from sanction under the State Proceedings Act which provides some immunity to public officials for actions taken in their official capacity. In fact, the act of withholding, hiding, or destroying information must be deemed to be actions outside of the scope of their official duties for them to be fully liable for those actions.

In conclusion, there are some very worrying provisions of the ATI Bill that make surveillance more likely and that threaten the right to privacy for ordinary citizens. We believe that the original Freedom of Information Bill of 2002 was far more progressive in this regard. We advocated for the withdrawal of the ATI Bill and the reintroduction of the original Freedom of Information Bill which provides greater safeguards for freedom of expression and the right to privacy. The original Freedom of Information Bill also provided for greater accountability of public bodies. As we have seen repeatedly with laws such as the Public Order Act, having bad provisions in a law may be more detrimental than having no law at all as it is liable to be weaponised against citizens to curb their rights and freedoms. A good law must be clear, unambiguous, must not be detrimental to society’s interests, and should not have discriminatory application. Neither should good law be arbitrary. The lack of definition of key terms in the Bill would leave the interpretation of key terms in the Bill, such as “public interest” and “public funds” in the hands of the very bodies that we seek information from. This is highly undesirable. We believe that the current ATI Bill falls short of this standard. We subsequently call for the ATI Bill to be withdrawn and replaced with the Freedom of Information Bill of 2002 which complies with international best practice and is progressive in nature. We believe that the original Freedom of Information Bill also largely meets the aspirations of the people of Zambia who for three decades have been calling for greater accountability and transparent in government and public bodies.

Chapter One Foundation is a civil society organisation that promotes and protects human rights, the rule of law, and social justice in Zambia. Please follow, like, and share our content on Facebook and LinkedIn under the page ‘Chapter One Foundation’ and on Twitter and Instagram under the name ‘@CofZambia’.

2 responses

verry interesting about your artcikel,

Yes