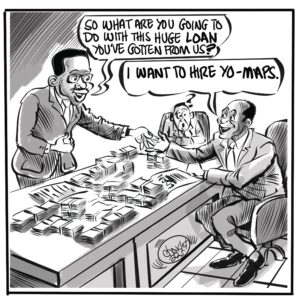

Corporate entities play a key role in the economy through labour income and capital investments. However, Companies have been used to conduct illegal activities such as money laundering, corruption, tax evasion or environmental exploitation just to mention a few. Following this realisation, many African governments now demand disclosure of beneficial ownership information. One of the means through which the Zambian government has done so is through the Companies Act no 10 of 2017 (“the Act”) and its 2020 Amendment, which creates a requirement of beneficial ownership. Nonetheless, the Act falls short of some of the provisions that are pertinent for enhancing beneficial ownership transparency. Therefore, in this week’s piece, we will discuss how the Act can be enhanced through the incorporation of international guidelines. We start by highlighting some of the inadequacies of the Act and later propose solutions.

In recent years, global emphasis has been placed on understanding and disclosure of beneficial ownership information. It is noteworthy that in some cases the beneficial owner and legal owner could be the same person, however, this is far from always being the case. Therefore, it is important to distinguish beneficial ownership from legal ownership. Beneficial ownership refers to an individual or entity controlling or benefiting from a company’s assets, even if their details are not on official documents. Legal ownership, on the other hand, is the documented ownership of property, established through title deeds, contracts, and registration certificates. Unlike beneficial ownership information, legal ownership information is always readily available, hence the emphasis on beneficial owner transparency.

Although Zambia has made progress in incorporating beneficial ownership into the Act and other laws, there still exist gaps and challenges that lead to ineffective implementation of it in line with international standards. Some notable challenges Zambia is currently facing may be seen through the following provisions of the Act:

1. Section 12(3) (e) of the Act read together with form 21 makes it a mandate for information of true owners to be provided. Due to lack of awareness by community and entities regarding beneficial ownership, there is a misconception that providing personal information infringes on their right to privacy. Consequently, people either withhold information or provide incomplete or misleading information.

2. While Section 12 (3) (e) makes it a requirement to provide the Patents and Companies Registration Agency (PACRA) registrar with a statement of beneficial ownership information, it does not provide specific sanctions for failure to do so. Similarly, Section 21(3) which requires that any change in beneficial ownership should be notified to the registrar does not have sanctions attached to it. This entails that reliance is only on the general offences and penalty provided for under Section 372 and 373 respectively, which then makes it difficult to determine which offence applies to beneficial ownership. Therefore, the lack of specific sanctions for noncompliance, advertently providing false information or non/late/incorrect/incomplete submission is another hindrance to beneficial ownership transparency in Zambia.

3. Additionally, we have no strict enforcement system: For sanctions to be an effective deterrent, there is a need for an effective, specific, and legally mandated enforcement mechanism to monitor compliance and enforce sanctions where a company defaults to meet its obligation.

4. Furthermore, the Act lacks measures for systematic verification of self-reported data or reporting of incorrect information, which leads to data quality issues that undermine the effectiveness of disclosure. Despite Section 124(1) providing that the registrar should ascertain and verify beneficial ownership information before registration, PACRA only depends on the information on the application forms.

5. Section 270 (3) particularly requires public companies to lodge annual returns with the updated beneficial ownership information. The issue here is that this Section only requires a public company, thus, this creates a loophole that could be abused by other types of companies incorporated under the Act.

6. Albeit, Section 21 provides the establishment of a central register for companies incorporated, it comes with two challenges; conditioned accessibility of this information as it comes with a fee. The other challenge is the lack of linkage between the established register with other regulatory institutions which makes it difficult to enhance the disclosure of beneficial ownership information about companies operating in various sectors with their regulations.

Having looked at the shortcomings of the Act, this brings our discussion to a conclusion for this week. In next week’s piece, we will look at the global guidelines and solutions that Zambia can incorporate to address the challenges discussed and strengthen beneficial ownership transparency.

About the Author:

Lucy P. Musonda is an Advocate of the High Court of Zambia-AHCZ, she currently works for the Centre for Trade Policy and Development as a Legal Researcher. She holds an LLB from the University of Zambia and currently pursuing an MBA at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh School of Business.