Globally there has been an exponential rise in the use of digital technology. The information that individuals put into the digital space has now been commoditised. We see personal information being processed, used and transmitted in a way that infringes on the right to privacy. With this, countries worldwide recognise the need to create laws that protect and promote privacy rights of individuals. In an attempt to protect personal data, Zambia passed its first Data Protection Act, Number 3 of 2021 (the Act) on the 24th of March 2021. The Act was created with the aim of governing the use of individuals’ personal information. In addition, it seeks to prevent unlawful use, collection, processing, transmission and storage of personal information, thus protecting the right to privacy. Be that as it may, it is important to examine this vital piece of legislation and ask ourselves does it really serve the purpose it was intended?

Zambia is a party to the Malabo convention which sets an international standard of data protection laws. Article 9 (2) (a) of the Malabo conversion provides that the conversion will not apply to personal information processed by a natural person within the exclusive context of his/her personal or household activities, provided such data is not for systematic communication to third parties or for dissemination. Section 3 of our Act has a similar provision. It limits its application by not applying to the processing of an individual’s personal data as long as it is for personal use. It would have been preferable if the Act used more specific language. For instance, the Act should have precisely indicated that it would not apply to the processing of personal information by an individual provided the information is not communicated to third parties or disseminated as couched in the Malabo conversion. Drafting the section in a clear manner would ensure that individuals know categorically their limits when using another person’s data.

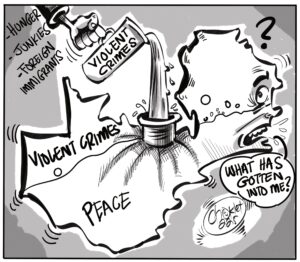

The Act also has several provisions that are likely to be abused. Section 8 of the Act outlines in very broad terms the wide powers of the appointed inspectors to inspect and enter premises, to access, search and seize equipment, books, documents, and records after obtaining a warrant. Under the provision, inspectors have powers to search property, including a dwelling house. Section 10 further authorizes a law enforcement officer to seize and detain property which an inspector has reason to believe was used to commit an offence. The determination of what amounts to the use of property to commit an offence is left to the interpretation of the inspector. Although an inspector must obtain a warrant prior to such a search and/or seizure, there is no minimum requirement for an inspector to substantiate their application for a warrant. In addition, the Act provides no limits as to the nature, scope or duration of warrants. These powers bestowed on inspectors are broad and threaten to limit the very essence of protection of all persons from the deprivation of their property, and the right to privacy as guaranteed by Articles 16, and 17 of the Constitution.

Section 9 of the Act authorises an inspector to arrest a person, without a warrant, where the inspector has reasonable grounds to believe that the person is about to commit an offence under the Act. This means an arrest can be made on mere suspicions, especially since the Act does not define the scope of what would amount to a reasonable ground. Such power to arrest without a warrant and in the absence of proof is unfettered. It is an unjustifiable threat to the right to liberty guaranteed in Article 13 of the constitution as no safeguard has been placed to ensure that such grounds or reasons are legitimate.

According to Section 26 of the Act failure to adhere to the terms of surrender attracts a sentence of imprisonment for a term of ten years upon conviction.

This penalty is stiff and is likely to prohibit persons from registering as data controllers or data processors. It is absurd that the penalty for failure to comply with conditions of surrender are even more stiff than the penalties for unlawfully disclosing sensitive personal data to another person. Such an offence attracts imprisonment of up to a term not exceeding two years as provided in section 73, when the aim of the Act is to prevent unlawful use, and transmission of personal information. In comparison to the Malabo convention which provides protection of data, whilst maintaining other rights and freedoms, the Act in its current form has the ability to take away rights and certain freedom. For instance, the Malabo convention in Article 12 (3) (4) does provide for the penalties for failure to comply by a data controller, but such penalties do not include imprisonment as stipulated in our Act.

The Data Protection Act, was enacted with a view to control the digital space, but due to its vague provisions and broad discretionally powers bestowed on certain officers the Act instead has the potential to infringe on certain constitutionally guaranteed rights and freedoms. The Act was enacted to reflect the Malabo convention. Sadly, in as much as Zambia has worked towards implementing the convention, it is clear that the the Data Protection Act gives protection with one hand and takes rights away with the other.

Chapter One Foundation is a civil society organization that promotes and protects human rights, the rule of law, constitutionalism, and social justice.